-

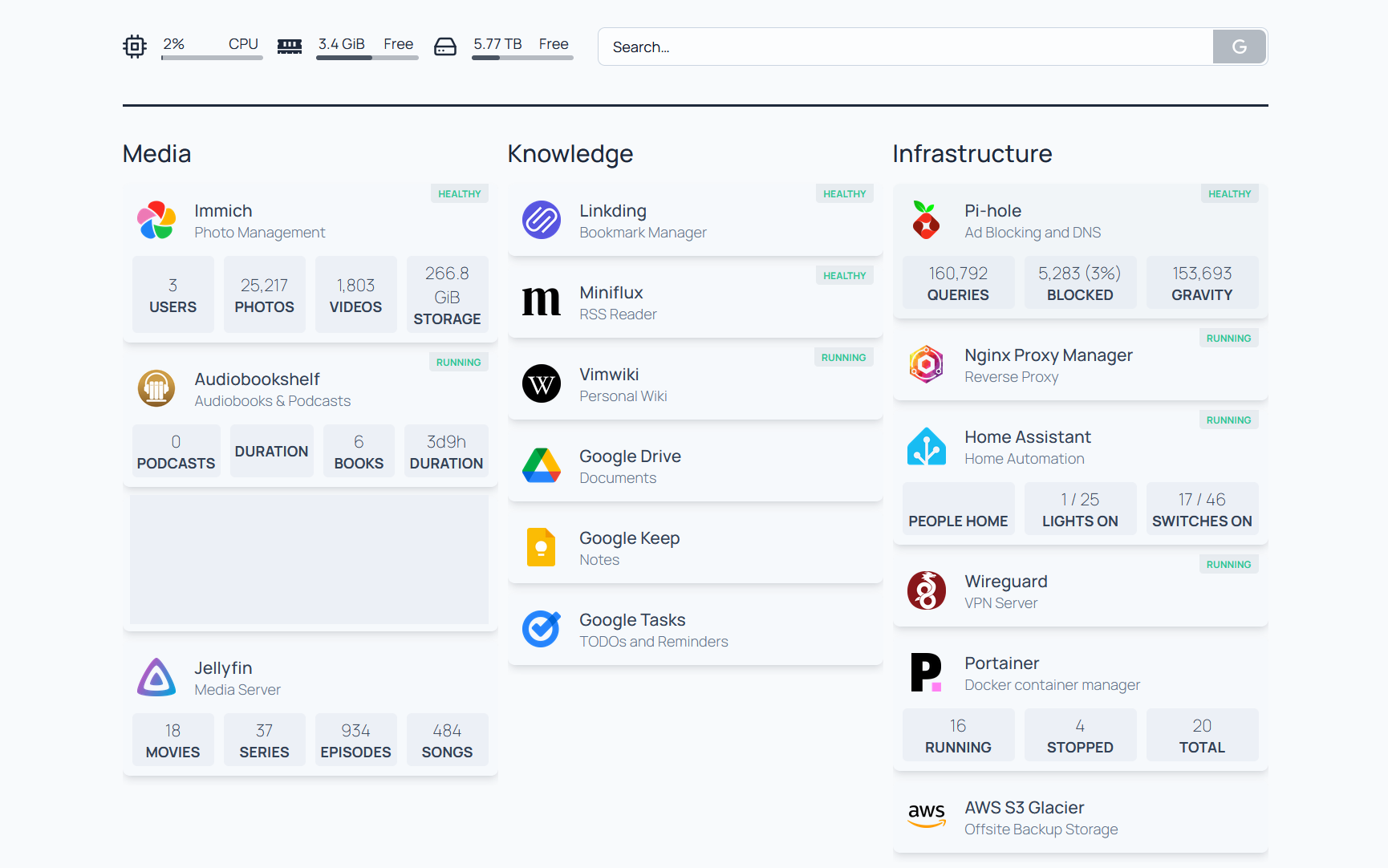

Homepage for a home server

I have a NAS (Network Accessible Storage) which doubles as a home server. It’s really convenient to have a set of always-on, locally hosted services - which lets me read RSS feeds without distractions, have local photos storage solution, or move away from streaming services towards organizing my (legally owned) collections of movies, shows, and audiobooks.

At this point I have 20-or-so services running and sometimes it gets hard to keep track of what’s where. For that - I found Homepage. A simple, fast, lightweight page which connects to all of my services for some basic monitoring, and reminds me what my service layout looks like.

Here’s what I built:

I love that the configuration lives in YAML files, and because the page is static - it loads real fast. There are many widgets which provide info about various services out of the box. It’s neat.

There’s definitely a question of how much I’ll keep this up-to-date: it’s not an automatically populated dashboard, and editing is a two-step process (SSH into the machine, edit the YAML configs) - which adds some friction. We’ll have to wait and see, but for now I’m excited about my little dashboard.

-

What I won't write about

Howdy.

I’ve been writing a lot more over the past year - in fact, I’ve written at least once a week, and this is article number 60 within the past year. I did this for many reasons: to get better at writing, to get out of a creative rut, play around with different writing voices, but also because I wanted to move my blog from a dry tech blog to something I myself am a little more excited about.

I started this blog in 2012, documenting my experiences with various programming tools and coding languages. I felt like I contributed by sharing tutorials, and having some public technical artifacts helped during job searches.

Over the years I branched out - short reviews for books I’ve read, recounts of my travel (and turning my Prius into a car camper to do so), notes on personal finance… All of this shares a theme: descriptive writing.

I feel most confident describing and recounting events and putting together tutorials. It’s easy to verify if I’m wrong - an event either happened or didn’t, the tool either worked - or didn’t. And I was there the whole time. That kind of writing doesn’t take much soul and grit, and while it’s pretty good at drawing traffic to the site (eh, which is something I don’t particularly care about anymore), I wouldn’t call it particularly fulfilling. Creatively, at least.

I’m scared to share opinions, because opinions vary and don’t have ground truth. It’s easier to be completely wrong, or to look like a fool. I don’t want to be criticised for my writing. Privacy is a matter too - despite writing publicly, I consider myself to be a private person.

So, after 13 years of descriptive writing, I made an effort to experiment in 2025. I wrote down some notes on parenthood, my thoughts on AI and Warhammer, nostalgia, identity, ego… I wrote about writing, too.

It’s been a scary transition, and it still is. I have to fight myself to avoid putting together yet another tutorial or an observation on modal interfaces. I’ve been somewhat successful though, as I even wrote a piece on my anxiety about sharing opinions.

But descriptive writing continues sneaking in, trying to reclaim the field.

You see, I write under my own name. I like the authenticity this affords me, and it’s nice not having to make a secret blog (which I will eventually accidentally leak, knowing my forgetfulness). I mean this blog has been running for 14 years now, that’s gotta count for something.

But writing under my own name also presents a major problem. It’s my real name. If you search for “Ruslan Osipov”, my site’s at the top. I don’t hide who I am, and you can quickly confirm my identity by going to my about page. This means that friends, colleagues, neighbors, bosses, government officials - anyone - can easily find my writing. If there are people out there who don’t like me - for whatever reason - they can read my stuff too.

The more I write, the more I learn that good writing is 1) passionate and 2) vulnerable (it’s also well structured, but I have no intention of restructuring this essay - so you’ll just have to sit with my fragmented train of thought).

It’s easy to write about things I’m passionate about. I get passionate about everything I get involved in - from parenting and housework to my work. I write this article in Vim, and I’m passionate enough about that to write a book on the subject.

Vulnerability is hard. Good writing is raw, it makes the author feel things, and leaves little bits and pieces of the author scattered on the page. You just can’t fake authenticity. But here’s the thing - real life is messy. Babies throw tantrums, work gets stressful, the world changes in the ways you might not like. That isn’t something you want the whole world to know.

Especially if that world involves a prospective employer, for example. So you have to put up a facade, and filter topics that could pose risk. I’m no fool: I’m not going to criticize the company that pays me money. I like getting paid money, it buys food, diapers, and video games.

I still think it’s a bit weird and restrictive that a future recruiter is curating my writing today. The furthest I’m willing to push the envelope here is my essay on corporate jobs and self-worth.

Curation happens to more than the work-related topics of course. And that might even be a good thing. I don’t just reminisce about my upbringing. It’s a brief jumping off point into my obsession with productivity. Curation is just good taste. You’re not getting my darkest, messiest, snottiest remarks. You’re getting a loosely organized, tangentially related set of ideas. Finding that gradient has been exciting.

So, here’s what I won’t write about. I won’t share too many details about our home life. I won’t complain about a bad day at work. I won’t badmouth people.

But I will write about what those things feel like - the tiredness, the frustration, the ego.

-

Starting daycare is rough

Picture this: it’s 2 am. My kiddo is mouth breathing, loudly as she’s whining trying to fall asleep. Poor kid is running a fever. She’s drooling and scratching her face because she’s teething. No one in this household have slept well for weeks.

Everyone warned me that starting daycare will be rough. Everyone said oh hey, you’ll be sick all the time, your kid will be sick all the time, you’ll be miserable.

How bad could it be, right? Well, it’s bad. I don’t have a thesis for this post, I just need to vent. And yeah, sick kiddo is why I’m almost a week behind my (self-imposed) writing schedule.

Because over the past month this child was supposed to be in daycare (which isn’t cheap, mind you), she’s been home at least 50% of the time. And oh how I wish I could just blame daycare and say they don’t want to deal with yet-another-whiny-and-snotty-kid, I also empathize with both the overworked daycare employees who want to send her home.

Being a daycare worker isn’t easy, and I’m sure constant crying doesn’t help. When we were touring daycares, we’ve noticed something interesting: every place posts pictures, names, and mini-resumes for their teachers - and what stands out to me is that many have 1-2 years of experience. Not just at the daycare we picked, but among the majority of places we’ve toured.

Turns out daycare workers have a significantly above average turnover - like a press release from Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland indicating that the “turnover among childcare workers was 65% higher than turnover of median occupation”. The wages are low, the hyper-vigilance needed to keep infants and toddlers alive takes a toll on a nervous system, and the job is mostly sedentary - with lots of sitting on the floor and baby chairs watching the little demons crawl around.

Where was I? Oh, yeah, I don’t know what daycare workers are going through, but I empathize.

But I also empathize with myself (d’oh), working half-days and taking unexpected time off as my clingy, cranky, annoyed toddler wants demands some kind of attention. The kiddo’s sick and wants to be held 24/7. But you know what else? She gets bored, so she wants to play. But it’s hard to play when you’re being held. So crying tends to be a good solution.

And all of that is on top of the fact that this disease-ridden potato has gotten me sick, 4 times and counting in the past 3 months. Her and mom get pretty sick, but - probably because mom’s body is working for two - they do mostly fine. Sick, but manageable.

I on the other hand just feel like I’m barely able to survive some days. Everything hurts, and nothing helps. I used to like being sick, in the same ways I love rainy days. You get an excuse to veg out - yeah, it’s unpleasant, but you get to binge your favorite shows or play some sick-friendly games. You order in or your partner cooks for you. You drink tea and such. It’s cozy.

And most importantly for someone who struggles to sit still, I don’t feel any guilt for doing nothing. It’s nice.

But being sick with a kid - hell no. Gone is the guilt-free experience. Kid’s sick, wife’s sick, I’m sick. We’re all rotating through our chores, we all have our roles to play. One of us soothes the baby, one of us cooks and cleans, one of us cries and leaves a trail of snot on the floor.

So yeah, here I am, on my 4th sickness, taking a breather to write up this note while mom took the kiddo to get some fresh air.

Send help. No, really - shoot me an email to tell me I’m not alone and you’ve survived this. Or maybe tell me why you also enjoy how being sick gives you a permission to be lazy. Someone please normalize my experience!

-

Japan's etiquette is weird

We went to Japan last month, and I’ve finally found the time to put together my notes. I’ve been meaning to write this for a while - my scribbles have been sitting in a text file, judging me.

We spent time in Ho Chi Minh (or Saigon if you’re old) before heading to Tokyo, and the contrast was so striking that I can’t stop thinking about it. Both incredible places, both completely different in ways I find genuinely fascinating - and completely hilarious.

Japanese people love to queue. I say this with admiration - it’s a cultural commitment I find both impressive and, in its most intense forms, comedy gold. Food? Queue. Taking a train? Queue. Elevator? Believe it or not, queue. I’m half convinced there’s a queue somewhere just for the privilege of standing in another queue.

And oh, the “close door” button on elevators. I witnessed something beautiful in Tokyo: the unmistakable rapid-fire mashing of that button the moment someone steps inside, even when - especially when - they can clearly see me approaching. It’s not malicious. I don’t think it’s even personal. It’s just… commitment to efficiency, extending all the way down to shaving those precious three seconds off the elevator door’s natural rhythm. Dude. I can see you. I’m right here.

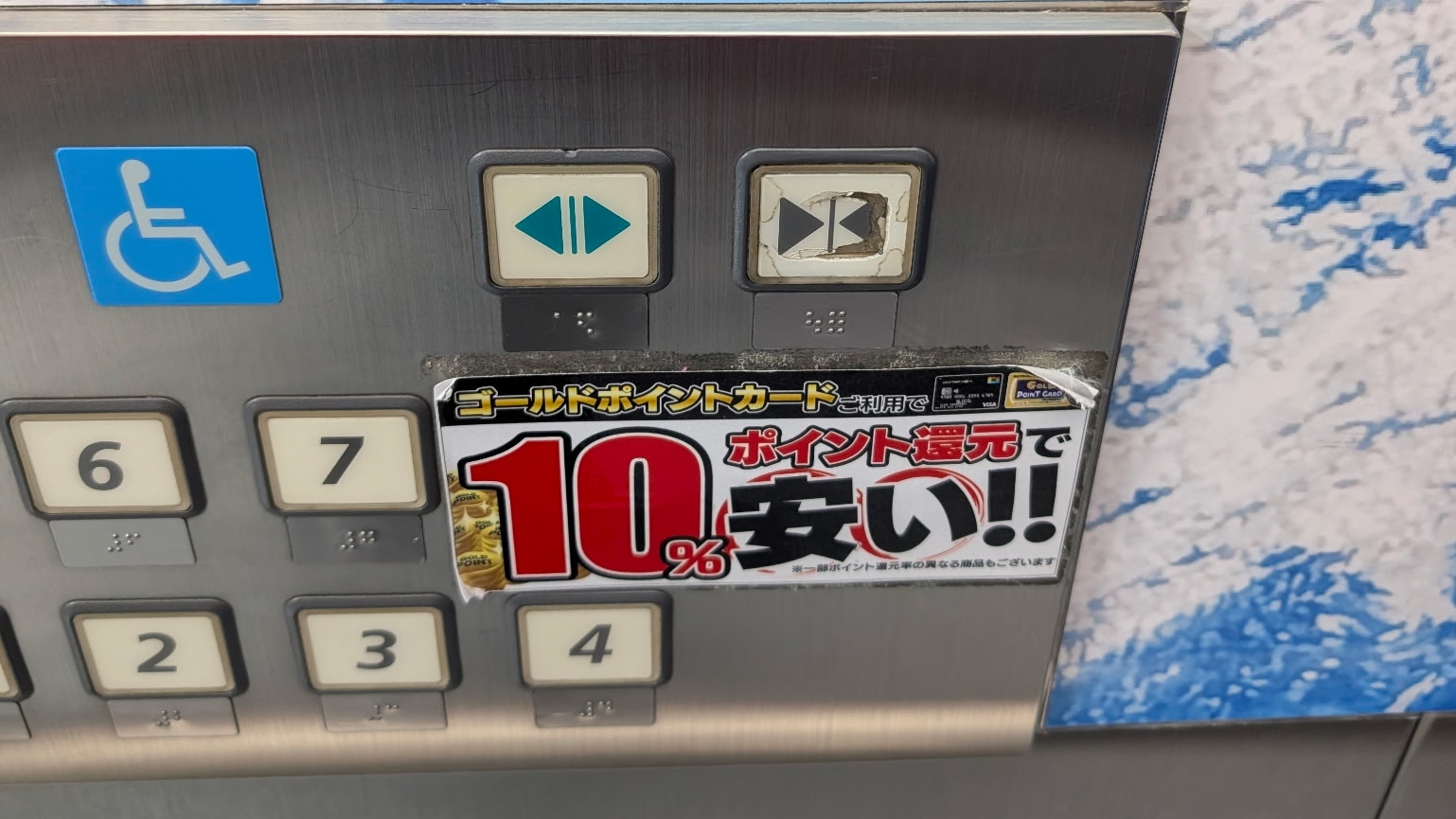

Just look at the wear pattern on these elevator butons:

That’s what most elevators looked like.

The subway has a similar choreography. People pushing past you with practiced, almost apologetic urgency. Same with the konbini - if you’re in someone’s path to the onigiri section, you will be navigated around like a minor obstacle in an otherwise frictionless system. It’s nothing personal, you’re just in the way of the system.

Here’s what really struck me about Tokyo: you can go an entire day without having a meaningful interaction with another person. And I don’t mean that in a sad, lonely way - I mean it as a genuine observation about how thoughtfully everything is designed.

Restaurants have ticket machines where you order and pay before sitting down. Your food arrives. You eat. You leave. No one needs to talk to you. No one wants to talk to you - and that’s not rudeness, it’s infrastructure. The system handles everything. The mother’s rooms were cleaner than our own house (and I mean that literally - I looked around one of those nursing rooms and felt personally called out by my own bathroom at home). Everything has a place, a purpose, a queue.

It’s impressive. It’s hyper-functional. And after coming from Vietnam, the contrast was jarring.

In Vietnam, you cannot avoid interacting with people. It’s physically impossible. Every transaction feels impromptu, like you’re the first customer they’ve ever had and everyone’s figuring it out together in real-time.

Paying a bill at a restaurant? That might involve three people, a calculator that may or may not work, and a vague sense that the total is more of a collaborative suggestion than an established fact. “How much?” “Uh… let me ask my cousin.” This is not a criticism - it’s delightful. There’s a warmth to that chaos.

Service in Japan is polished to perfection, almost rehearsed - which makes sense, given the cultural emphasis on hospitality. In Vietnam, it felt more like someone’s aunt decided to help out at the family restaurant. Less professional, maybe, but somehow warmer? The friendliness wasn’t performance, it was just… how things were.

Traveling with an infant is exhausting in ways I couldn’t have predicted, but it’s also like carrying around a small social barometer. You get to see how different cultures engage with kids, and the contrast between Tokyo and Ho Chi Minh was striking.

In Ho Chi Minh, my daughter was a celebrity. Everyone wanted to hold her, talk to her, feed her something we probably shouldn’t let her eat. The warmth was overwhelming - chaotic, often not always hygienic, but deeply human. Strangers cooing at her, shopkeepers waving, someone’s grandmother stopping us to admire the baby. Human connection wasn’t optional - it was woven into the fabric of every interaction.

Tokyo was different. Not cold, exactly. Just… distant. People are exceptionally polite, but there’s a respectful bubble around families. No one’s stopping you on the street to admire your baby. Which is fine! Privacy is a gift, especially when you’re tired. But it’s noticeable when you’ve just come from a place where your kiddo was treated like a visiting dignitary.

In Japan, you can live in a world of seamless, frictionless interactions. Machines handle payments, apps handle navigation, and the physical infrastructure is designed to minimize the need for human contact. It’s efficient, clean, and just really cool.

In Vietnam, the infrastructure almost forces you to connect. Nothing is fully automated. Everything requires negotiation, conversation, a smile and a nod - it’s messy. It’s inefficient by lack of design. And it’s incredibly human.

I’m not saying one is better than the other - that’s too simple, and frankly, kind of reductive. But I do find myself wondering what we optimize away when we make things frictionless. What do we gain, and what do we lose? Japan’s systems are a marvel, but they also create a world where you can be surrounded by millions of people and have a difficult time connecting with them. Vietnam’s chaos forces connection, for better or worse.

Or maybe I’m taking huge leaps in judgement based on a few weeks in countries where I didn’t speak the language and barely knew anyone.

It was a good trip. We had a great time, even if traveling with an infant is a whole thing. We’ve been unable to do many fine dining establishments because of the kiddo, and honestly? We felt much more comfortable and relaxed eating at a regional equivalent of Denny’s. It’s nice not to feel too bad when your baby starts happily throwing food around.

Maybe next time we bring parents along. Outsourcing some of the infant-wrangling sounds appealing.

-

The illusory truth effect

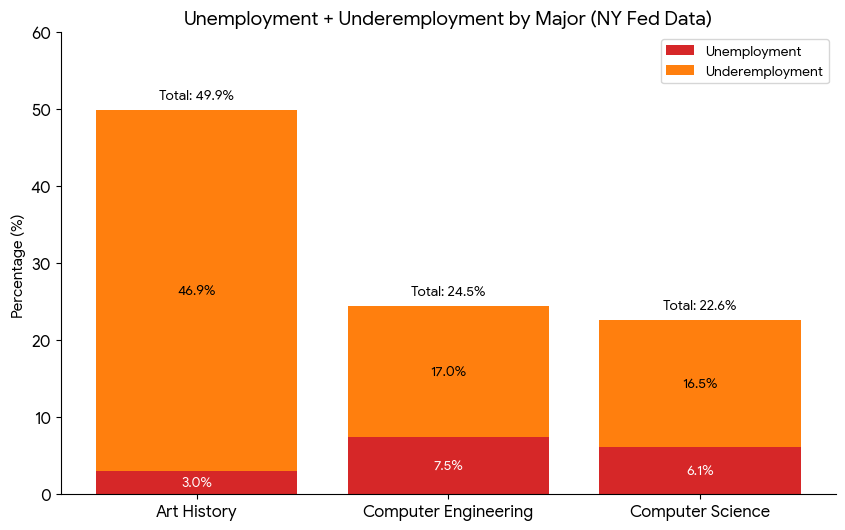

I’m a bit late with this, but here’s an interesting headline: “Liberal arts students have lower unemployment rates than computer science students according to the NY Fed”. It’s a headline I saw early last year, took a note to read further, and just rediscovered the headline when cleaning up my notes.

Here’s an article from The College Fix from June 20, 2025: Computer engineering grads face double the unemployment rate of art history majors. In the article, the author claims:

The stats show art history majors have a 3 percent unemployment rate while computer engineering grads have a 7.5 percent unemployment rate. Computer science grads are in a similar boat, with a 6.1 percent rate.

Ok, let’s find if this lines up with what NY Fed says:

Major Unemployment Underemployment Art history 3% 46.9% Computer engineering 7.5% 17.0% Computer science 6.1% 16.5% Oh, what’s that number next to “unemployment”? Uh-oh. Underemployment accounts for people working in a job which does not require a bachelor degree. This means that a computer engineering graduate is working a tech job, while an art history major takes up work in a fast food restaurant. And all of a sudden, the picture shifts. 17% of computer engineering majors were underemployed, while a whopping 46.9% of art history graduates weren’t utilizing their degree.

This article is one of many, which cherry-picked data from the NY Fed and made outrageous claims. Further, the data is from 2023, which the article above mentions near the end, in passing. That’s a pretty relevant bit, for an article written in 2025, isn’t it?

For me this brought up a question of digital hygiene and how the headlines I see affect us.

I have seen this headline many times throughout the year - I never read through content, but over time the headline stayed in my memory.

The illusory truth effect is the cognitive bias where repeated exposure to a statement makes it seem more truthful, even if it’s known to be false.

I really did believe that CS graduates had lower employment than art history majors. Don’t get me wrong, the job market for newgrads is oh-so-brutal, and the future prospects are murky. Which probably made it easier to believe such an outrageous claim.

Yes, disproving the headline took all of 10 seconds, but how many headlines do you see a day? What other misinformation cements itself in your head?

And ultimately, is it better to limit access to such information, or - however impractical - try to verify everything you see?