Japan's etiquette is weird

We went to Japan last month, and I’ve finally found the time to put together my notes. I’ve been meaning to write this for a while - my scribbles have been sitting in a text file, judging me.

We spent time in Ho Chi Minh (or Saigon if you’re old) before heading to Tokyo, and the contrast was so striking that I can’t stop thinking about it. Both incredible places, both completely different in ways I find genuinely fascinating - and completely hilarious.

Japanese people love to queue. I say this with admiration - it’s a cultural commitment I find both impressive and, in its most intense forms, comedy gold. Food? Queue. Taking a train? Queue. Elevator? Believe it or not, queue. I’m half convinced there’s a queue somewhere just for the privilege of standing in another queue.

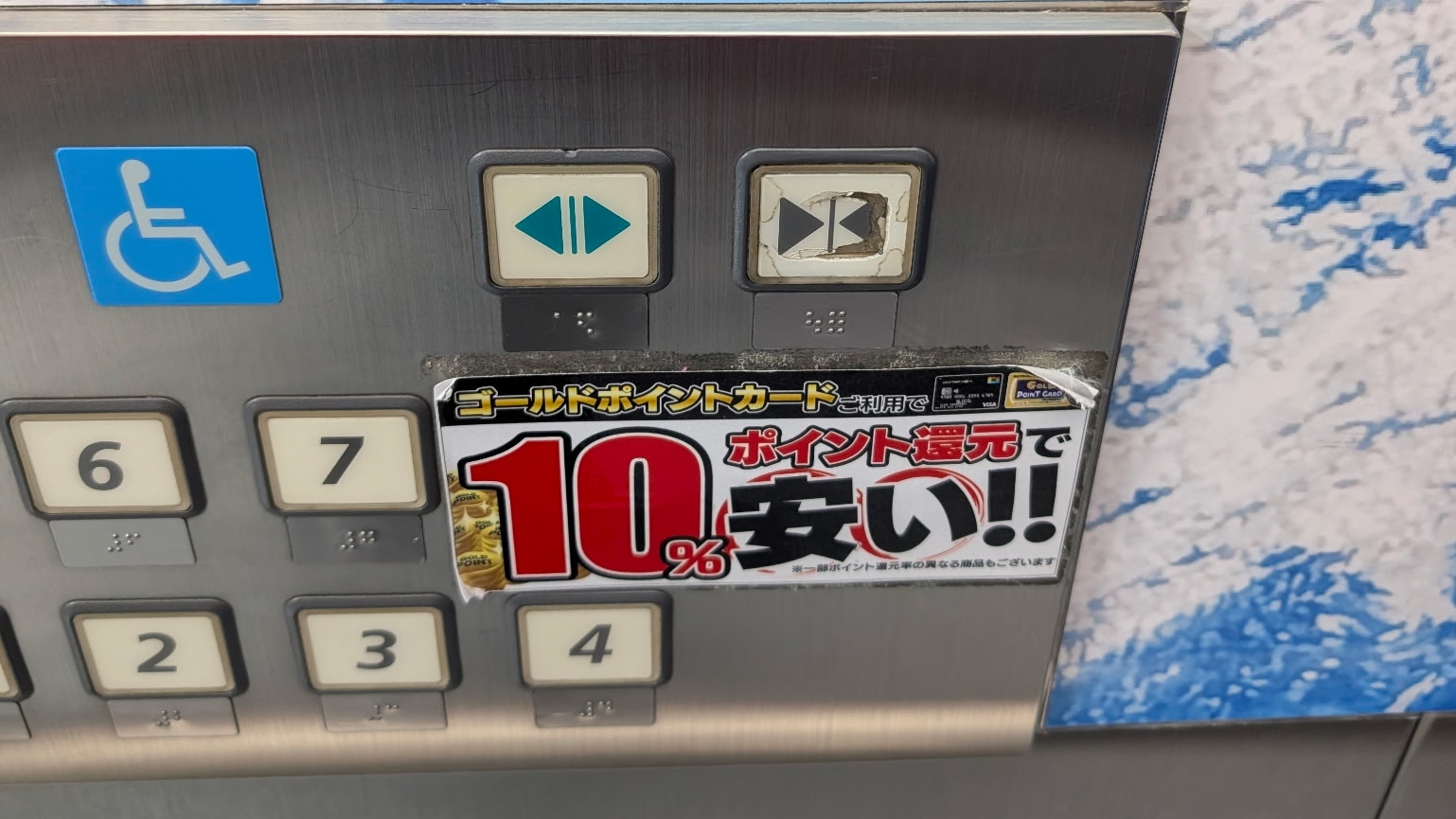

And oh, the “close door” button on elevators. I witnessed something beautiful in Tokyo: the unmistakable rapid-fire mashing of that button the moment someone steps inside, even when - especially when - they can clearly see me approaching. It’s not malicious. I don’t think it’s even personal. It’s just… commitment to efficiency, extending all the way down to shaving those precious three seconds off the elevator door’s natural rhythm. Dude. I can see you. I’m right here.

Just look at the wear pattern on these elevator butons:

That’s what most elevators looked like.

The subway has a similar choreography. People pushing past you with practiced, almost apologetic urgency. Same with the konbini - if you’re in someone’s path to the onigiri section, you will be navigated around like a minor obstacle in an otherwise frictionless system. It’s nothing personal, you’re just in the way of the system.

Here’s what really struck me about Tokyo: you can go an entire day without having a meaningful interaction with another person. And I don’t mean that in a sad, lonely way - I mean it as a genuine observation about how thoughtfully everything is designed.

Restaurants have ticket machines where you order and pay before sitting down. Your food arrives. You eat. You leave. No one needs to talk to you. No one wants to talk to you - and that’s not rudeness, it’s infrastructure. The system handles everything. The mother’s rooms were cleaner than our own house (and I mean that literally - I looked around one of those nursing rooms and felt personally called out by my own bathroom at home). Everything has a place, a purpose, a queue.

It’s impressive. It’s hyper-functional. And after coming from Vietnam, the contrast was jarring.

In Vietnam, you cannot avoid interacting with people. It’s physically impossible. Every transaction feels impromptu, like you’re the first customer they’ve ever had and everyone’s figuring it out together in real-time.

Paying a bill at a restaurant? That might involve three people, a calculator that may or may not work, and a vague sense that the total is more of a collaborative suggestion than an established fact. “How much?” “Uh… let me ask my cousin.” This is not a criticism - it’s delightful. There’s a warmth to that chaos.

Service in Japan is polished to perfection, almost rehearsed - which makes sense, given the cultural emphasis on hospitality. In Vietnam, it felt more like someone’s aunt decided to help out at the family restaurant. Less professional, maybe, but somehow warmer? The friendliness wasn’t performance, it was just… how things were.

Traveling with an infant is exhausting in ways I couldn’t have predicted, but it’s also like carrying around a small social barometer. You get to see how different cultures engage with kids, and the contrast between Tokyo and Ho Chi Minh was striking.

In Ho Chi Minh, my daughter was a celebrity. Everyone wanted to hold her, talk to her, feed her something we probably shouldn’t let her eat. The warmth was overwhelming - chaotic, often not always hygienic, but deeply human. Strangers cooing at her, shopkeepers waving, someone’s grandmother stopping us to admire the baby. Human connection wasn’t optional - it was woven into the fabric of every interaction.

Tokyo was different. Not cold, exactly. Just… distant. People are exceptionally polite, but there’s a respectful bubble around families. No one’s stopping you on the street to admire your baby. Which is fine! Privacy is a gift, especially when you’re tired. But it’s noticeable when you’ve just come from a place where your kiddo was treated like a visiting dignitary.

In Japan, you can live in a world of seamless, frictionless interactions. Machines handle payments, apps handle navigation, and the physical infrastructure is designed to minimize the need for human contact. It’s efficient, clean, and just really cool.

In Vietnam, the infrastructure almost forces you to connect. Nothing is fully automated. Everything requires negotiation, conversation, a smile and a nod - it’s messy. It’s inefficient by lack of design. And it’s incredibly human.

I’m not saying one is better than the other - that’s too simple, and frankly, kind of reductive. But I do find myself wondering what we optimize away when we make things frictionless. What do we gain, and what do we lose? Japan’s systems are a marvel, but they also create a world where you can be surrounded by millions of people and have a difficult time connecting with them. Vietnam’s chaos forces connection, for better or worse.

Or maybe I’m taking huge leaps in judgement based on a few weeks in countries where I didn’t speak the language and barely knew anyone.

It was a good trip. We had a great time, even if traveling with an infant is a whole thing. We’ve been unable to do many fine dining establishments because of the kiddo, and honestly? We felt much more comfortable and relaxed eating at a regional equivalent of Denny’s. It’s nice not to feel too bad when your baby starts happily throwing food around.

Maybe next time we bring parents along. Outsourcing some of the infant-wrangling sounds appealing.