Opinions in the age of technocratic totalitarianism

Dear reader, you’re in luck. I was going to spit out more uneducated opinions about how AI might or might not destroy art, but instead I’ll be talking about technocratic totalitarianism, and having said opinions. As always, thanks to Patrick for getting the thought train started through his thoughtful email forwards.

I haven’t finished college. I studied aerospace engineering for about two years: this was back in Russia, where education was free - or actually the opposite - I got paid a small stipend to study. Structured curriculums felt mind-numbingly monolithic, and at the same time I struggled to wrap my head around some subjects. The stipend wasn’t enough to keep me in a university though, and after two years I wanted a major change, so I packed a suitcase and moved to the United States.

If aerospace engineering didn’t work out, I always planned to go into software engineering. It seemed not particularly hard, it was interesting, and it lent itself well to unstructured learning I so very much enjoy. Lady luck smiled, and that worked out - I’ve been working in software engineering for nearly 15 years.

I’m taking you through this preamble for a reason: I’m not particularly well educated, I don’t have an academic background, and I don’t fetishize formal education. Good on you for getting a PhD, but I can’t get myself to place much value on that fact alone. Full transparency: I spelled aerospace engineering wrong when I first published this article, which only illustrates my point. And yet, I found myself nodding along as I was reading Cal Newport’s latest blog post:

“We hesitate to take a strong stance because we fear the data might reveal we were wrong, rendering us guilty of a humiliating sin in technocratic totalitarianism, letting the messiness of individual human emotion derail us from the optimal operating procedure.” - Cal Newport, Don’t ignore your moral intuition about phones

And it hit me. The quiet, persistent anxiety that hums beneath every opinion I hold. Despite my disdain for the academic institution, I’ve internalized one of its worst dogmas: that any belief not reducible to a peer-reviewed study is fundamentally illegitimate.

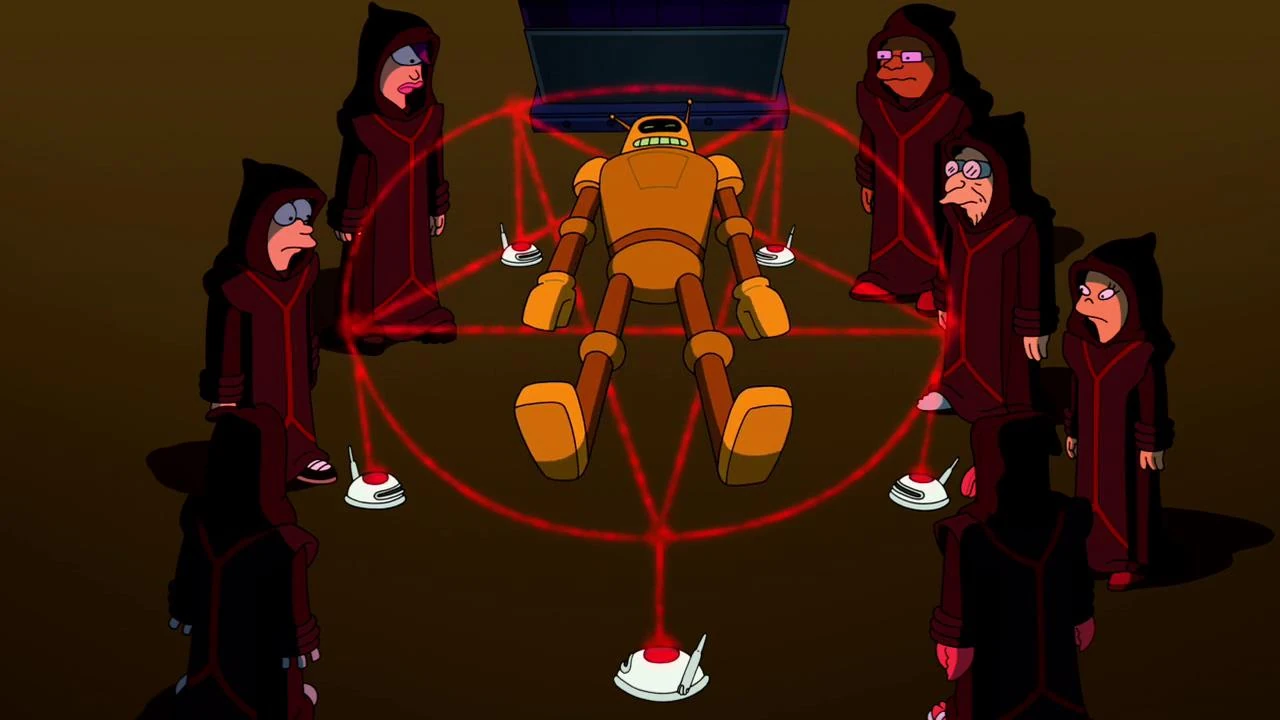

Yeah, I’m a technocratic totalitarian on the inside, worshipping science - turns out I am the tech-priest. A blind faith that a world is a complex machine, every aspect of which can be optimized, figured out, and rationalized. In a temple of technocratic totalitarianism being wrong is a “humiliating sin”, and ultimate act of heresy. And being a devout follower of my faith, a zealot, I fell into shying away from holding strong opinions.

Part of this came from my childhood - I was generally a gifted child, and things came easy to me. School was trivial, new languages weren’t hard to learn, and the only time I’ve faced intellectual adversity was in a university - and my fierce disdain for authority played a huge part in that too (but that’s a story for another day). I grew up with a belief that I’m smart, capable, and nothing is beyond my grasp if I put my mind to it (thanks, mom). A decade and a half of working in tech has played a role too. Surrounded by deeply technical peers and academics, the beliefs rubbed off on me. Software engineering being perceived as a precise and purely mathematical craft, corporate focus on numbers and metrics, and a call for every decision being backed by data only entrenched my beliefs.

And it’s really, really hard to hold opinions outside of a narrow field I’m able to build deep expertise in. So here I am, going through life, scared to have opinions about things because deep down I’m afraid to be proven wrong, which isn’t just a social failure - but a violation of my deeply held core beliefs.

Which brings me to parenthood. Watching my daughter grow has made me think about what it means to be a human. About deeply seeded biological instinct, fundamentally irrational behaviors, intuition, intangible human connection, love, and the joys of existing in this world.

For me, parenting is a deeply instinctual activity. While I tried to approach child rearing from a perspective rooted in research, turned out 1) there’s really not that much science about children out there, and 2) babies aren’t inherently rational and logical human beings.

When I started researching baby slings to wear my little one, I’ve read a lot about hip dysplasia - it’s a condition in newborns, where the hip bones don’t fit in the joint sockets right. And there’s lots of “maybes” on the subject, and one point stuck in my mind: “we are very likely to never know if baby wearing impacts hip dysplasia as studying this on infants would be deeply unethical”. And yeah, science shouldn’t really toy with children’s futures, and it largely doesn’t, and because of it raising children isn’t as well understood despite it being an activity humanity has lots of practice with.

And with many decisions, we just had to go with our gut, advise from parents, friends, and doctors - most of which was hearsay. The technocrats could burn me at the stake for this!

And then we met Leila (name changed for privacy). Leila is a lactation consultant - turns out breastfeeding is hard, since both the baby and the mom are figuring out how to do this together for the first time. Leila is also a postpartum doula, a certified marriage councilor, a church pastor, essential oil distributor, and she even has a YouTube plaque sitting in her office, sitting on a shelf among the all the crystals.

Here’s the thing, Leila was instrumental to getting our daughter to take on a breast. And it didn’t stop there. She’d make many recommendations - from holistic medicine to bizarre techniques that I’m pretty sure summon some kind of spirits. And guess what, when it’s 3 am and my baby hasn’t stopped crying for six hours - you’re damn right I’ll follow the instructions to the letter. Because those things worked.

Why did the techniques work? I’m too sleep deprived to analyze or care. They just worked.

In certain social circles - the ones I tend to find myself in often - intuition is devalued. It’s treated as a crutch, something deeply stepped in biases and human emotion, something to be avoided if possible. It’s the enemy of the optimal, and Leila should’ve been the final boss in my crusade against irrationality.

But at 3 am, with a screaming infant, you can’t run a regression analysis on the efficacy of spiritual-adjacent rocking techniques. You don’t get to wait for a double blind, peer-reviewed studies. You do what works. And Leila’s effectiveness isn’t based in a methodology that can be verified, but something I’ve taught myself into dismissing: embodied wisdom. A messy collection of experience, tradition, and gut feelings.

This is the inflection point: that’s when the technocrat in me had a meltdown. I couldn’t file Leila under the science label, nor could I label her as a fraud. Life isn’t a set of engineering problems that require precise data-backed solutions, and I’d argue engineering problems don’t always require precise, data-backed solutions either.

Raising a child is a deeply human problem - a chaotic, messy, sleep-deprived relationship with an infant often breaks all logic. And parenthood forced me to revisit the lens through which I see the world around me.

Science is an indispensable tool, but it’s a terrible god.

I was talking about opinions, wasn’t I? Well, parenthood opened up a new mental framework. You may have engaged with the results of this framework on my blog if you’ve read any other pieces this year.

I exist in spaces that worship metrics, and often if something can’t be measured - it doesn’t exist. Robert McNamara, who led the U.S. Defense Department during the Vietnam War, solely relied on quantitative metrics - body counts, sorties flown - to gauge success. Needless to say, he wasn’t very successful in the war efforts. I’ve fallen into this trap a countless number of times, most recently when I realized I pursued high view counts for my blog, for whatever reason. This religious pursuit of truth leaves little room for nuances of being human.

When I was talking about this article to my wife, she made a point I’d like to share: we don’t differentiate well between opinions and facts, and when we do, we discount the former. And I’ve been excited to share and discuss opinions more, and it’s been an enriching experience. It invites dialogue, facilitates sharing unfinished ideas, and helps me learn about the world.

Opinions are unique, colorful, and diverse. Opinions are made of scraps of knowledge, thoughts, feelings, and experiences glued together by an essence of humanity. I’m excited about sharing my opinions and I care about hearing yours (shoot me an email).