In defense of quality

The Internet whispers a constant message: you should be doing more. I remembered a video I stumbled upon a while back. Some productivity influencer, barely old enough to grow a mustache, was detailing their morning routine. They were up at 3 am, of course. By the time the sun rose, they’d read an entire book, run ten miles, and meditated on a mountaintop while simultaneously coding a new killer app, all fueled by a kale smoothie that cost more than my lunch.

I didn’t feel inspired. I felt tired.

There’s a constant pressure in the background of modern life to keep up. The informational landscape has gotten particularly good at creating an illusion of scarcity, a fear that you’re falling behind. This is doubly true if you work in tech, where productivity and growth are treated not just as a badge of honor, but as a competitive sport. You must consume more, learn faster, ship quicker.

But this pressure is a trap. It pushes us further towards ever-increasing quantity, while the real value - in our work, in our thinking, and in our lives - has always been found in the deliberate pursuit of quality.

Let’s be clear: this feeling isn’t your fault. It’s a feature, not a bug. The platforms where we spend our time are engineered for this exact purpose. The endless scrolls, the auto-playing videos, the short-form feeds that evaporate from memory the second they’re gone - it’s all optimized for one thing: for you to watch it from beginning to end, and then watch more just like it. It’s content designed to be consumed and to do nothing else.

This ecosystem thrives on the illusion of knowledge. We have endless summaries, TL;DRs, and AI-powered tools that can give you the synopsis of any book in seconds. We skim headlines and read the bullet points, mistaking this fleeting familiarity for understanding. We are becoming masters of the shallow factoid, the talking point without substance.

This isn’t a new thought. “Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips” (Sparrow et al., 2011) showed that we don’t bother remembering information we believe we can easily look up later. More recently, “People mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own” (Ward, 2021) took it a step further, finding that when we have access to the internet, we often mistake its knowledge for our own. We don’t just offload the facts; we internalize the false confidence of knowing, without ever having done the work.

A couple of years ago, I read Greg McKeown’s Essentialism. The core concept isn’t revolutionary, but the way I engaged with it was for me. I read it slowly. A little bit each morning, with a cup of coffee. I took notes in the margins, underlining passages, connecting the ideas to my own experiences. It became a paced, deeply personal experience. I’d mull over a chapter for days, bringing up concepts in conversations with my wife or colleagues. Because I gave the ideas time to breathe, they began to stick. They integrated themselves into my thinking in a way that no summary or 10-minute video review ever could. The book holds a place in my head not because of what it said, but because of how I listened.

This is the difference between knowing about something and understanding it. We internalize concepts slowly. Mastery and satisfaction don’t come from the frantic consumption of a hundred different things, but from immersing yourself in one thing, from wrestling with it, from letting it change you. It’s the long email thread with a friend debating a single concept. It’s the quiet hour spent thinking, not just consuming. That is where the real work happens.

This mindset of quantity over quality bleeds into other areas of our life. It shows up at work, rebranded as “growth mindset.” On the surface, it’s wonderful. Who wouldn’t want to grow? But it can be a bit of a grift. The corporate mandate to be “constantly upskilling” - often on your own time and at your own expense - isn’t always for your benefit. It’s for the company’s. It ensures the workforce is perpetually churning, learning the next new framework without ever pausing to question if it’s better than the last.

Worse, this mindset even poisons our leisure. Go search for a new hobby. You won’t just find tutorials; you’ll find guides on how to monetize it, how to build a personal brand around it, how to become the most efficient and optimized practitioner of it. I just want to watch TV and paint miniatures; I have no desire to win a trophy or launch a Patreon for my technique. The pressure to get better, faster, stronger turns the very activities meant to be a refuge from work into just another form of it.

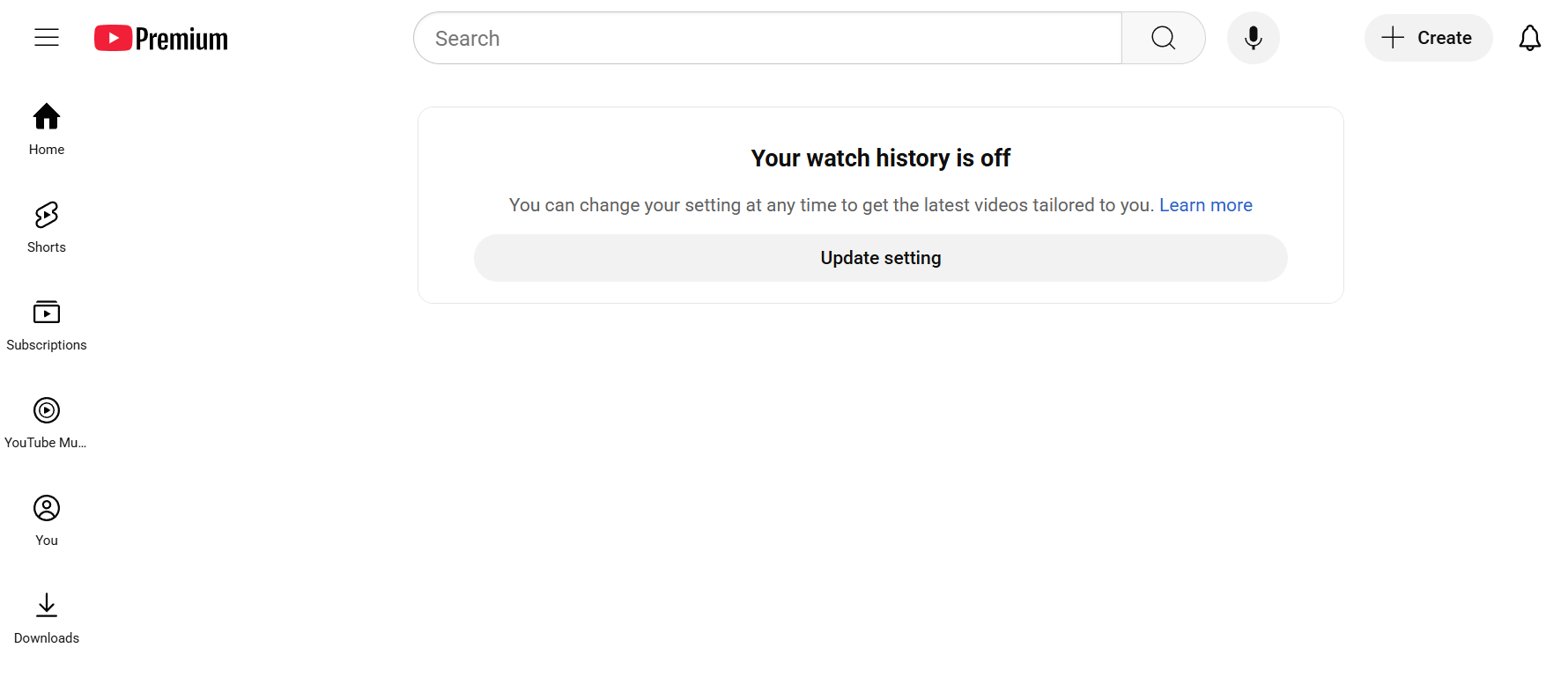

The solution for me wasn’t to learn faster, but to learn better, which often means learning slower. This requires making a conscious choice to step away from the algorithm. I turned off my YouTube history, which mercifully nukes the recommendation feed and the YouTube Shorts (here’s what my YouTube home page looks like).

I left sites like Reddit years ago and haven’t missed them. Instead, I’ve returned to powerful tools like RSS or email. Subscribing directly to a person’s blog or newsletter is an act of defiance. It’s a choice to engage with a whole person’s train of thought, complete with their quirks and tangents, rather than consuming the single, out-of-context snippet that an algorithm decided was worthy of your attention.

This post was inspired by Nikhil’s You don’t need AI summaries, tldr or to be on top of things, which I’ve read back in April, and it’s been since sitting as a starred article in my RSS reader. I’d occasionally get back to scan through it, think about the message and take notes about what I’d like to say in response. And I’m glad I took my time and gave Nikhil’s post the mindspace it deserved.

I’ve leaned into more of a evangelist approach in this article, and I know I’ve simplified the topic. The older I get, the more allergic I feel to dealing in absolutes, but I felt like there’s a good message here. For completeness sake, algorithmic discovery isn’t all bad: it can help us engage in broad variety of content we wouldn’t otherwise seek out, and it can provide a platform to people who deserve it at virtually no cost to them. This piece isn’t about selling a new anti-productivity framework or joining another counter-culture trend. But I think there’s something to be said about reclaiming agency in an increasingly noisy world. By choosing depth over breadth, and quality over quantity, I found more genuine understanding, satisfaction, and a little more peace.