Category: Philosophy

Subscribe via

RSS

.

RSS

.

-

The illusory truth effect

I’m a bit late with this, but here’s an interesting headline: “Liberal arts students have lower unemployment rates than computer science students according to the NY Fed”. It’s a headline I saw early last year, took a note to read further, and just rediscovered the headline when cleaning up my notes.

Here’s an article from The College Fix from June 20, 2025: Computer engineering grads face double the unemployment rate of art history majors. In the article, the author claims:

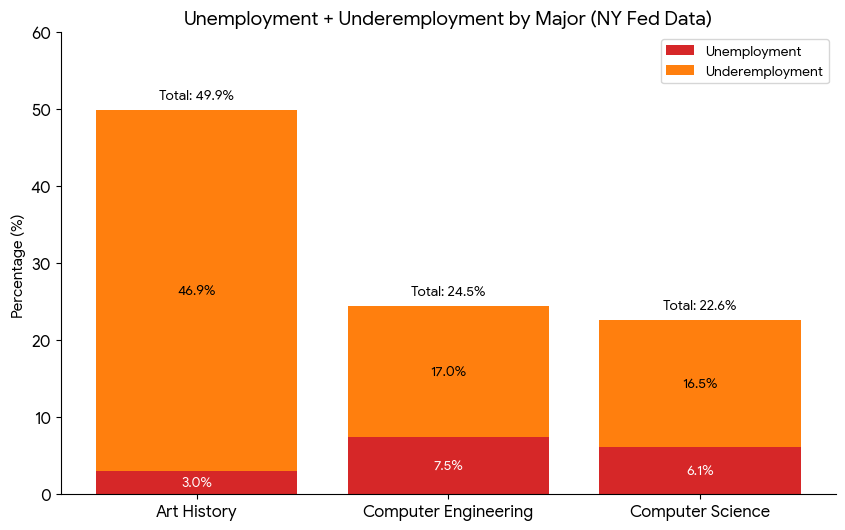

The stats show art history majors have a 3 percent unemployment rate while computer engineering grads have a 7.5 percent unemployment rate. Computer science grads are in a similar boat, with a 6.1 percent rate.

Ok, let’s find if this lines up with what NY Fed says:

Major Unemployment Underemployment Art history 3% 46.9% Computer engineering 7.5% 17.0% Computer science 6.1% 16.5% Oh, what’s that number next to “unemployment”? Uh-oh. Underemployment accounts for people working in a job which does not require a bachelor degree. This means that a computer engineering graduate is working a tech job, while an art history major takes up work in a fast food restaurant. And all of a sudden, the picture shifts. 17% of computer engineering majors were underemployed, while a whopping 46.9% of art history graduates weren’t utilizing their degree.

This article is one of many, which cherry-picked data from the NY Fed and made outrageous claims. Further, the data is from 2023, which the article above mentions near the end, in passing. That’s a pretty relevant bit, for an article written in 2025, isn’t it?

For me this brought up a question of digital hygiene and how the headlines I see affect us.

I have seen this headline many times throughout the year - I never read through content, but over time the headline stayed in my memory.

The illusory truth effect is the cognitive bias where repeated exposure to a statement makes it seem more truthful, even if it’s known to be false.

I really did believe that CS graduates had lower employment than art history majors. Don’t get me wrong, the job market for newgrads is oh-so-brutal, and the future prospects are murky. Which probably made it easier to believe such an outrageous claim.

Yes, disproving the headline took all of 10 seconds, but how many headlines do you see a day? What other misinformation cements itself in your head?

And ultimately, is it better to limit access to such information, or - however impractical - try to verify everything you see?

-

I shouldn’t have bought that keyboard

A little over a month ago I bought a keyboard for my phone. Here’s what I wrote:

I’ll follow-up in six month to year to see if that’s just a gimmick purchase. Or maybe I end up drafting up my next book using this thing - we’ll just have to see.

Well, it was a gimmick. It’s a great keyboard, and I’m sure niche use cases will come up here and there, but… yeah, a gimmick. There I was, on our family trip to Japan and Vietnam, excited about all the writing I might do from a hotel room, or maybe in a coffee shop, or even on the long flight.

But here’s the thing, we travel with an infant. Yeah, that’s an important part I kind of glanced over. There really isn’t that much free time to write when you either entertain, feed, or sleep the little potato, and when you’re not doing that - you just want to lay down, or maybe talk to your partner because you two haven’t had uninterrupted conversation in months.

But even beyond that, I massively overestimated my own desire to write when I’m on vacation. I love writing, and it did find a few occasions to plop open the device and jot down some notes, but ultimately writing is work. Rewarding work I enjoy, but it’s still work. I don’t like to work on vacation. I like to chill.

With hindsight, as I’m reading the excited mini-review for my little ProtoARC XK04, I can clearly see how naive I was, and how I fell for the idea that all I need is a sleek little keyboard, and I’ll write more! I will be oh-so productive!

My partner and I often talk about the barrier to doing things (tm) and how it interacts with the stuff you buy.

I don’t really need a fancy pair of running shoes to start running. And I don’t need a fancy notebook or a nice keyboard to write. Yes, it’ll probably get me excited to get into the hobby, but this type of excitement passes quickly.

A few years back - half a decade or so - I lived a little too far from work to bike. A little too close to justify driving. My wife and I decided we’ll get me an ebike, ebikes aren’t cheap, or at least they weren’t back then. We got one, and it was exactly what I needed: a little more power to make my hilly 30 minute commute by bike a no-brainer. I biked 5 days a week, and I did so for years until we moved.

Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to tell when something is the right tool for the job, or ultimately just a gimmick and a waste of money. Companies have gotten very good at selling you a belief in a version of yourself - you don’t buy an item, you think about who you will become (with a help of said item). I think of myself as somewhat frugal and prudent with money, but this just comes to show how easy it is to fall into that trap.

So yeah, I didn’t write more because I bought a little keyboard. But I am writing more (twice a week for nearly a year now) because I made a commitment, because I enjoy the creative process, and because it makes me feel good.

-

Home is where my stuff is

When I was in my 20s, decluttering was easy. I didn’t have a lot of stuff. I came to the US with a single suitcase, and I mostly kept my stuff contained to that suitcase for years. It was nice - every time I’d move when renting rooms (which was often), I’d go through all my stuff, put it back in the suitcase, and be back on the move.

My mom lived through the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which instilled a scarcity mindset - something I naturally inherited. You don’t own too many things, you take care of what you own, you don’t throw stuff away. Stuff was hard to come by, so you respected it.

The irony is that this mindset both prevents accumulation and makes decluttering harder. You don’t buy frivolously, but you also don’t discard easily. Every object earned its place.

I slowly started accumulating stuff. First, it was the computer. My love of both tech and games is no secret, so I upgraded from a tiny netbook into a full-blown gaming PC. It wasn’t anything to write home about, but it was big enough that it would no longer fit in my suitcase. There was a monitor too, so two things that I had to have. It was the first time I needed help moving - and my last landlord was nice enough to help - a suitcase, a PC tower, and a monitor.

I still didn’t have too much stuff, and a dedicated PC really was a great investment for a gaming enthusiast like me. I got a bicycle too, but that was really a transportation method, and while it was yet another thing - it made me healthier and opened up the city around me.

Clutter escalated once I rented an entire place to myself. All of a sudden I needed furniture, moving up from prefurnished rooms. At first I lived in a tiny studio which didn’t even have a functional kitchen. A bed, a clothes rack, and a desk for my computer.

The studio was cramped and utilitarian, but I remember a specific kind of peace. Everything I owned was visible from the bed. No hidden boxes, no “I should really go through that” guilt. I could see all my stuff. I didn’t realize at the time that this was a temporary state - not a lifestyle I’d chosen, but a constraint I’d graduate out of. Minimalism is easy when the life is not yet complicated.

I won’t bore you with every place I lived in throughout my life, so let’s fast forward a decade. My wife, child, and I live in our house in San Diego, and have a lot more stuff now. Naturally, all the furniture, clothes for three, kitchen stuff (I love to cook), so many different things. There’s all the home improvement stuff - hey, gotta keep the paints, the brushes, the hammers and the drills. Need all of that to take care of the house we own. I have many more interests these days too - from miniature painting to, as of recently, 3D printing. All of the hobbies take up valuable space.

I had a director, Luke, who was complaining about business travel - and me, being a young tech professional, could not relate. He would say “Home is where my stuff is. I like my stuff.” And now that I have more stuff - ugh, I get it.

I go through annual decluttering, Konmari exercises (“does this bring me joy?”). But it’s hard, because buying stuff is really easy. A few clicks and tomorrow (or sometimes even today) there’s a box on your porch. Look, just last week I talked about a phone keyboard I bought. The friction is gone. The decision to acquire takes seconds; the decision to discard takes emotional labor.

Here’s what I’ve realized: every object I own is a fossil. A little sediment left by a past version of myself.

The gaming PC wasn’t clutter - it was proof that I’d made it, that I could afford something nice for once, that I wasn’t just surviving anymore. The drill isn’t clutter - it’s homeowner-me, a version of myself that 20-something-year-old me with his suitcase couldn’t have imagined. The 3D printer is current-me’s curiosity, an exploration of a hobby. The miniature paints are the version of me that finally has time for hobbies just for the sake of having hobbies.

This is why decluttering is so hard. It’s not really about tidiness. It’s about deciding which past selves get to stay.

That drawer with random cables? That’s “I might need this someday” me - the Soviet scarcity mindset my mom handed down. The programming books I’ll never open again? That’s a young programmer me from a decade ago. The fancy kitchen gadgets I used twice? That’s “I’m going to become someone who makes pasta from scratch” me. Aspirational me. He didn’t pan out, but he tried.

Some of these versions of myself are still relevant. Some aren’t. The hard part isn’t identifying which is which - it’s accepting that letting go of the object means letting go of that version of me. Admitting that I’m not that person anymore. Or that I never became the person I bought that thing for.

I don’t think the goal is to minimize anymore. I’ve read the minimalism blogs, I’ve seen the photos of people with one bag and a laptop living their best life in Lisbon. Good for them, I lived that life before - hell, I lived out of my car for a year. But I have a partner, a kid, a house, and more varied interests. All of which come with stuff.

I want to be intentional about which identities I’m holding onto and why. Some sediment is just dirt - clear it out, make space, breathe easier. But some sediment is bedrock (I’m not a geologist, I don’t know rocks). The one suitcase life isn’t coming back, and that’s okay. I’m in a different stage of my life: I look back at my “simple life” with longing, but I enjoy my life today even more - or maybe just differently. I certainly enjoy it in the way important to me today.

So now when I declutter, I try to ask a different question. Not “does this bring me joy?” but “which version of me needed this, and do I still want to carry him forward?” Sometimes the answer is yes. The drill stays. The 3D printer stays. The gaming PC - upgraded many times now - stays. And sometimes the answer is: that guy did his best, but I’m someone else now. Thanks for getting me here. Into the donate pile you go.

It doesn’t make decluttering easy. But it helps me make peace with the mess. The suitcase me is not coming back, and that’s probably for the best - he didn’t really have much of a life yet. I’ve got more stuff now. I’ve got more me now. I’ll figure out what stays.

It’s been 10 years since I first wrote about my experience with minimalism. Reading through it now - many of the story beats are similar, but the perspective changed. Funny how that works…

-

How a nasty cold fixed my diet

Our whole family has been sick with a really nasty cold. It probably has something to do with the fact that our infant licks every surface and object she comes in close proximity with. I’ve been sick for 11 days and counting (don’t worry, I’ve seen a doctor, I have my antibiotics now), and this is just the worst.

But it did fix our eating out problem. You see, we love good food, we live in a foodie neighborhood, and we eat out a little too much. We want to eat out a little less, if only to enjoy the times we do even more. And most importantly, we want to stop eating out just because we’re lazy.

And we’re often lazy.

But guess what, when you’re sick, the idea of going out, spreading your germs, being uncomfortable and being a public menace just isn’t a great one.

It’s much, much easier to eat at home than to eat out right now. So we’ve been eating at home.

This idea of reducing friction to do the right thing reminded me of the period in my life when I got in pretty good shape by biking every day. I lived not too far from the office, but the nature of Bay Area traffic meant that it would take me up to 40 minutes to make a fairly short commute. I could commute at a different time - earlier or later, or I could bike. Because it would consistently take me 30 minutes to bike to the office, and if I was late, or if I was being lazy (which I am often), biking was the fastest option. My office being Google, having showers in the office helped, of course.

I’ve been trying to recreate making it more convenient to do the right thing ever since. We don’t have a driveway here in our house in San Diego - so driving often means losing a parking spot. This makes biking or walking a much more appealing - often an easier option.

Back to better diet, I’ve been buying those yummy frozen meals from Trader Joe’s, because sauteing some Kung Pao chicken in the skillet is healthier, faster, and easier than getting takeout. It works, as long as we don’t run out of frozen food that is.

Are there ways you trick yourself into making better choices?

-

Ego and the moving finish line

This is an entry to the IndieWeb carnival on ego hosted by bix.

In case you don’t know me - I’m Ruslan. A father, a husband, and a big nerd for video games and optimization problems. A few years ago, I would’ve started this intro differently: “Hi, I’m Ruslan and I’m an engineering manager at Google.” Oh - I’m still a manager at Google, but my priorities in life are different, and the shift is driven by the way my relationship with ego has changed over the years.

Over a decade ago, in my early twenties, I seeked recognition. I wanted to be widely known and respected. I moved to the United States from another country, pursued a career in tech - hopping between companies until landing at Google. This was huge for me, as I admired the company growing up, and working at Google felt like a peak achievement for a little computer nerd like me.

But I haven’t really savored the accomplishment. Now that I got to Google, it was all about getting to the next level, getting a promotion, bumping up my salary, expanding my span of influence, and so on. I compared myself to other early-twenty-somethings. Look, Mark Zuckerberg started Facebook at age 19, and I’m already a few years behind! Did I want to start a company? No. Did I even like Facebook? No, I didn’t. But that didn’t stop me from comparing myself to others, and it leached the joy out of life.

The generational curse of productivity certainly has something to do with it - I couldn’t just relax and savor the victories. I had to work hard for the next milestone. But a huge driver behind my early professional achievements was my ego. I wanted to be the best, and I wanted others around me to know it. I simply didn’t know a different way to live.

Throughout my early years I was really concerned with what people thought about me. I still struggle with it. And professional success felt like a way to bring authority into the conversation - “look, you can’t think poorly of me, I’m mister big pants in a serious company”. Mind you, we’re talking about an imaginary conversation in my own head.

In my mid-twenties I met my now-wife, who had a much more balanced outlook on life. She’s a hard worker too, but her achievements weren’t driven solely by the need to be seen by others as something else. No, she simply did things she was good at, and did them well. There’s lots of professional pride, yes, but it just felt… healthier? We both were ambitious, we both wanted to do our work exceptionally well, but while I wanted to be seen as the best, she just cared about her craft - regardless of who’s watching.

That was a major change from how I approached life, and her attitude rubbed off on me. I tried to decouple my own self-image from my professional successes. I began to engage in hobbies for the sake of enjoyment.

Look, I started this blog back in 2012 to bolster my professional image. I wanted to appear attractive to prospective employers, and I wanted people to see how many important thoughts I have, and how many cool things I know. This blog is very different now, because I have less people I care to impress. I don’t want a large audience.

Do I get excited when an article I write goes viral or I get a royalty check from my book in the mail? Absolutely. But do I get worked up when only a single reader gets through the entirety of what I write? Not anymore, no, because my ego as a writer needs less feeding than it used to. That’s why I removed comments and other visible indicators of popularity on this blog (eh, and I just don’t want to be tempted by the pursuit of bolstering my own ego).

In my mid-30s, I care less about impressing people. It helps me be a better listener, a better friend, or even just a better fleeting acquaintance. I have richer interactions with others when I don’t try to impress them. It ain’t perfect, and I find myself struggling - but I feel like I’m on the right track. I know I’ll win when I won’t be checking the view counts on this piece though.

If you’re curious about what other writers have to say about ego, I recommend you check out other entries on IndieWeb Carnival: On Ego.

-

Appreciating impermanence

Our friends hosted dinner yesterday. They live just down the street, and they’ve been living through a major home renovation project for the past couple of years. The whole place is getting gutted, walls are coming down, and they’re meticulously building the home of their dreams. They just finishing the kitchen, and it’s a thing of beauty - the place just feels like their home.

What’s wild to me is that they’re in the middle of talks with a developer to sell the house to them, and the developer’s just going to tear it all down anyway. “What’s the point?”, I wondered. But for them, that’s not the point at all. They’re just enjoying the act of making the place they want to live in, and seem unconcerned that it’s all going to get destroyed, maybe even in a few months.

And that’s just a great, healthy approach to life. Life’s marred with impermanence - it always feels like there’s going to be a better, calmer, happier time. “We’ll do X once Y settles down” has been too common of a phrase in our household, and I’d like to break that cycle.

“I wish there was a way to know you’re in a good old days” - The Office

We are in the good old days, and visiting our friends was a great reminder of that, and a permission to not slow down building a life just because something might change in the future.

-

On corporate jobs and self-worth

As someone who works at a large corporation - Google - and someone who always thought working at Google would be really cool, I put a lot of my self-worth into my job. When things go well at work - I’m doing well. When they’re going awry - my well-being follows.

Yeah, that’s not a very healthy take, and I know it, but as someone who’s been in the tech industry for the past 14 years, it’s a difficult worldview to escape. At this point it’s probably a deep seated core belief.

A close friend of mine is leaving Google this week. She’s taking a voluntary exit program, which is effectively a more humane way for a large company to organize workforce reductions. It’s better than the layoffs we’ve also seen quite a few of lately. After being a model employee for the past decade, she’s leaving the company (and tech in general) to focus her passions elsewhere. She’s excited for the future ahead, and she’s lost too, and I think I would be too.

It’s understandable - humans are wired to want to provide some social value. You want to be working for the good of the tribe, and you want the tribe to see and recognize that. Moochers will be shunned, and in the olden days being shunned would spell certain death. People usually can only survive together, in a group.

But in a modern world, it’s remarkably hard to connect the value of the work you do to a greater whole, to the goodness of your tribe.

I had a short opportunity to not be in the workforce for 3 months as I took my paternity leave. I didn’t experience a sense of decreased self-worth, but many other factors were in play. Naturally, my daughter was born and it was exciting, and so many things were happening. Figuring out how to parent a newborn isn’t easy and doesn’t leave much room for existential crises. But there’s also a lot of social value to being a dad and raising a child, which felt extremely gratifying. I imagine if I were to just take extended time off without a purpose like that one - I wouldn’t be as satisfied, and I’d begin to question my own self-worth.

I’ve been an aspirational FIRE practitioner for over a decade. FIRE stands for Financial Independence Retire Early - a terrible acronym, but the idea behind it is solid: reduce expenses, increase income, invest the difference. Many FIRE practitioners retire in their 30s or 40s, but I’m not quite there, and I enjoy aspects of work (and paycheck doesn’t hurt, either). What I like about FIRE as a philosophy is that it forces me to confront what it’s like to not have to work. That’s the end goal after all, but hearing from my retired friends, it always sounds like you just replace old problems with new ones.

In the end, I feel like it all comes down to finding things to value about myself that are outside of the job. I’m learning that it’s all about moderation. I’m trying to find a way to balance the different parts of my life, so that no single aspect, like my career, outweighs all the others. Because I feel like when I put all my self-worth eggs in one basket, it’s not a question of if things will break, but when.

-

In defense of quality

The Internet whispers a constant message: you should be doing more. I remembered a video I stumbled upon a while back. Some productivity influencer, barely old enough to grow a mustache, was detailing their morning routine. They were up at 3 am, of course. By the time the sun rose, they’d read an entire book, run ten miles, and meditated on a mountaintop while simultaneously coding a new killer app, all fueled by a kale smoothie that cost more than my lunch.

I didn’t feel inspired. I felt tired.

There’s a constant pressure in the background of modern life to keep up. The informational landscape has gotten particularly good at creating an illusion of scarcity, a fear that you’re falling behind. This is doubly true if you work in tech, where productivity and growth are treated not just as a badge of honor, but as a competitive sport. You must consume more, learn faster, ship quicker.

But this pressure is a trap. It pushes us further towards ever-increasing quantity, while the real value - in our work, in our thinking, and in our lives - has always been found in the deliberate pursuit of quality.

Let’s be clear: this feeling isn’t your fault. It’s a feature, not a bug. The platforms where we spend our time are engineered for this exact purpose. The endless scrolls, the auto-playing videos, the short-form feeds that evaporate from memory the second they’re gone - it’s all optimized for one thing: for you to watch it from beginning to end, and then watch more just like it. It’s content designed to be consumed and to do nothing else.

This ecosystem thrives on the illusion of knowledge. We have endless summaries, TL;DRs, and AI-powered tools that can give you the synopsis of any book in seconds. We skim headlines and read the bullet points, mistaking this fleeting familiarity for understanding. We are becoming masters of the shallow factoid, the talking point without substance.

This isn’t a new thought. “Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips” (Sparrow et al., 2011) showed that we don’t bother remembering information we believe we can easily look up later. More recently, “People mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own” (Ward, 2021) took it a step further, finding that when we have access to the internet, we often mistake its knowledge for our own. We don’t just offload the facts; we internalize the false confidence of knowing, without ever having done the work.

A couple of years ago, I read Greg McKeown’s Essentialism. The core concept isn’t revolutionary, but the way I engaged with it was for me. I read it slowly. A little bit each morning, with a cup of coffee. I took notes in the margins, underlining passages, connecting the ideas to my own experiences. It became a paced, deeply personal experience. I’d mull over a chapter for days, bringing up concepts in conversations with my wife or colleagues. Because I gave the ideas time to breathe, they began to stick. They integrated themselves into my thinking in a way that no summary or 10-minute video review ever could. The book holds a place in my head not because of what it said, but because of how I listened.

This is the difference between knowing about something and understanding it. We internalize concepts slowly. Mastery and satisfaction don’t come from the frantic consumption of a hundred different things, but from immersing yourself in one thing, from wrestling with it, from letting it change you. It’s the long email thread with a friend debating a single concept. It’s the quiet hour spent thinking, not just consuming. That is where the real work happens.

This mindset of quantity over quality bleeds into other areas of our life. It shows up at work, rebranded as “growth mindset.” On the surface, it’s wonderful. Who wouldn’t want to grow? But it can be a bit of a grift. The corporate mandate to be “constantly upskilling” - often on your own time and at your own expense - isn’t always for your benefit. It’s for the company’s. It ensures the workforce is perpetually churning, learning the next new framework without ever pausing to question if it’s better than the last.

Worse, this mindset even poisons our leisure. Go search for a new hobby. You won’t just find tutorials; you’ll find guides on how to monetize it, how to build a personal brand around it, how to become the most efficient and optimized practitioner of it. I just want to watch TV and paint miniatures; I have no desire to win a trophy or launch a Patreon for my technique. The pressure to get better, faster, stronger turns the very activities meant to be a refuge from work into just another form of it.

The solution for me wasn’t to learn faster, but to learn better, which often means learning slower. This requires making a conscious choice to step away from the algorithm. I turned off my YouTube history, which mercifully nukes the recommendation feed and the YouTube Shorts (here’s what my YouTube home page looks like).

I left sites like Reddit years ago and haven’t missed them. Instead, I’ve returned to powerful tools like RSS or email. Subscribing directly to a person’s blog or newsletter is an act of defiance. It’s a choice to engage with a whole person’s train of thought, complete with their quirks and tangents, rather than consuming the single, out-of-context snippet that an algorithm decided was worthy of your attention.

This post was inspired by Nikhil’s You don’t need AI summaries, tldr or to be on top of things, which I’ve read back in April, and it’s been since sitting as a starred article in my RSS reader. I’d occasionally get back to scan through it, think about the message and take notes about what I’d like to say in response. And I’m glad I took my time and gave Nikhil’s post the mindspace it deserved.

I’ve leaned into more of a evangelist approach in this article, and I know I’ve simplified the topic. The older I get, the more allergic I feel to dealing in absolutes, but I felt like there’s a good message here. For completeness sake, algorithmic discovery isn’t all bad: it can help us engage in broad variety of content we wouldn’t otherwise seek out, and it can provide a platform to people who deserve it at virtually no cost to them. This piece isn’t about selling a new anti-productivity framework or joining another counter-culture trend. But I think there’s something to be said about reclaiming agency in an increasingly noisy world. By choosing depth over breadth, and quality over quantity, I found more genuine understanding, satisfaction, and a little more peace.

-

I love bad coffee and hate algorithms

I love bad coffee.

One of the least sophisticated ways of making coffee is to just brew some in a pot and pour it into a cup. America’s famous for its bad coffee. When asking for a cup of coffee in, say, Amsterdam or Paris, you often get a nice, skillfully brewed cup of espresso – concentrated caffeinated artistry. The bouquet of flavour in such creations is something to admire, really.

And yet, every time I travel outside of the United States, I miss my average cup-of-Joe. When I first came to the United States, I would occasionally stop by at a diner that would serve terribly burnt coffee that was probably sitting in a coffee machine all day. That brew wasn’t delicate or even particularly potent: it was a straightforward, unapologetic part of the landscape. And that sense of Americana stuck with me. It brings me warmth, and slowly sipping my terrible cup of coffee is a highlight of my day. There’s an unpretentious honesty to it that I find increasingly rare.

It’s in this appreciation for the simple and unadorned that I find a contrast to a broader trend. In an increasingly interconnected world, it’s easy to focus on wanting the best, or appreciating what we’re told is the best. We learn about the “top” dining places, the “must-have” brand for a pair of pants, the “best” everything. This pressure isn’t new, but the mechanisms delivering these suggestions have become incredibly sophisticated. Now, we’re constantly nudged, particularly through our digital interfaces and by algorithmic suggestions, towards a curated, supposedly superior experience, often designed more for broad appeal or engagement metrics than personal resonance.

Choosing “bad” coffee, then, can feel like a small act of rebellion.

It’s a quiet refusal to have my preferences dictated, whether by a food critic offline or the mighty algorithm online. It’s easy to lose sight of what you genuinely like when you’re bombarded with content – perfectly filtered, endlessly optimized – telling you that something else is “better.” It might be objectively better by certain metrics, it probably is, but it isn’t necessarily better for me.

Yes, the cat video YouTube’s algorithm surfaces might be, by its engagement data, the “best” piece of cat-related content currently available. But often, it has no real relation to me, to the quirky humor of people I actually know, or the niche digital spaces I would consider mine. There’s no personal history there, no shared context, just an echo of mass appeal. It’s the digital equivalent of a focus-tested AAA movie – technically proficient, but lacking a soul.

That diner coffee isn’t aspiring to be anything other than what it is; it hasn’t been A/B tested or optimized for viral sharing. It’s a personal anchor in a sea of imposed “bests,” a tangible connection in an often-intangible world.

This isn’t a wholesale rejection of quality or a Luddite call to abandon our digital tools. It’s about recognizing that personal resonance often trumps algorithmic perfection. It’s about the freedom to find joy in the imperfect, the idiosyncratic, the things that speak to us for reasons that don’t require external validation or a high engagement score.

Sometimes, that wonderfully “bad” cup of coffee isn’t just a beverage; it’s a small declaration of independence from the tyranny of the curated feed. And that, in its own quiet, un-optimized way, is deeply satisfying.

-

Reflections on my paternity leave

Google provides generous parental leave, and I’ve been able to take three months to spend at home with my newborn. I even have some more time I can take once my wife returns to work! For residents of the Land of the Free, it’s a lovely glimpse into having a social support net and worker protection. Could you imagine?

And let me tell you, not working for three months was really nice. My newborn arrived a bit early, so the start of my leave was frantic - one Friday evening my wife said she was feeling off, we went to a hospital, and by the next morning my kiddo was born. I didn’t get much chance to wrap things up at work, but with the newborn here I didn’t particularly care. Three months into my leave, I still don’t care, and it’s nice. I’m sure I won’t be able to keep not caring for long once I’m back at work though.

My kiddo spent the first week in NICU (for those of you without much trauma in life - that’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), and once the danger had passed, it was a positive experience. The nurses were knowledgeable, and it was nice having “world’s best paid babysitters” keeping an eye on my baby 24/7. While my wife was recovering I spent most of the time with the kiddo - and turns out having a kiddo comes with a lot of downtime. I booted up my trusty Nintendo Switch, loaded Skyrim for the umpteenth time, and spent hours day and night gaming away while my kiddo was asleep on my chest. Man, newborns sleep a lot.

The kiddo started gaining weight, and we were ready to be discharged. Before being sent home we even managed to sneak away to a restaurant and celebrate our little victory! It’s been a long and perilous journey for our family, and it was a lovely opportunity to connect while the NICU nurses kept our tiny one safe. Although we were sent home without adult supervision, how dare they?! NICU bootcamp was tremendously helpful, and after the first couple of sleepless nights, we started figuring things out. That’s when this whole leave started feeling like a retirement preview, in a good way.

I wouldn’t consider myself a workaholic. I generally try to keep my work to under 40 hours a week, and I make sure to disconnect from work. I tend to give my work 110% while I am at work, which does tend to have a negative effect on me when things don’t go my way - that’s when my hours slip, and my ability to fully disconnect crumbles. I’m only human after all.

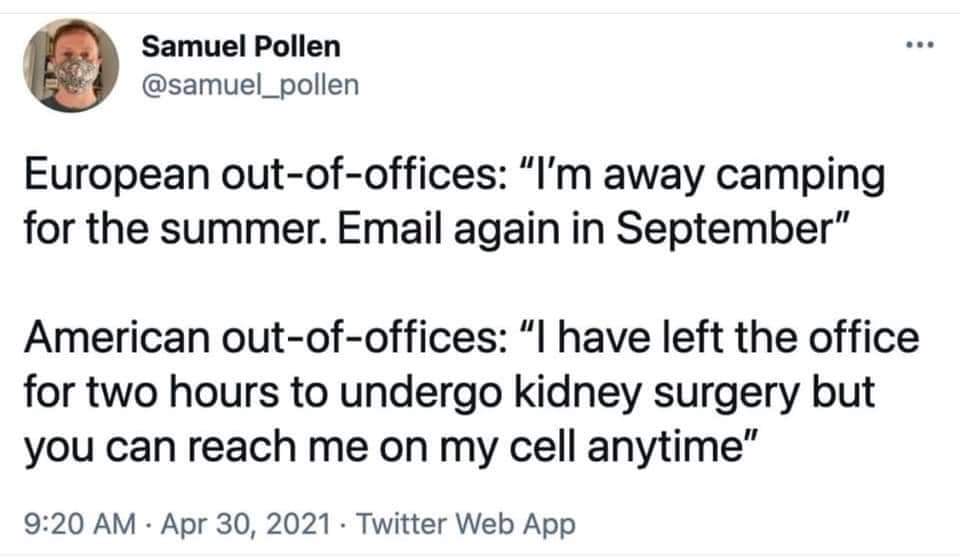

And I don’t take nearly enough vacation. I have generous vacation days (although nothing compared to how much our European colleagues get), but I think the American corporate culture has a hold on me. There’s a major sense of FOMO, and it feels like there’s never a good time to disconnect. There’s a lot of pressure to continue working towards the next milestone, next project, next promotion - “I’ll take time off after that”. And I just never do.

My wife and I manage occasional trips, but anything longer than a week is rare and stands out, and I often get nudged by corp systems “Take your vacation days or they’ll disappear” (ugh, why don’t you pay me the difference instead?).

All that to say, in nearly 15 years I’ve been in the workforce, I’ve never been off work for this long. And as someone who’s been glorifying early retirement and saving away for a rainy day for a decade now, this leave started to feel like an early retirement trial run. And I loved it!

Now, back to bringing our baby home: after settling into life, I started having lots of free time. It was a different kind of free time - there was lots of it, but none of it was on my schedule. If my partner felt generous, I might get nearly a full day to myself, or an hour every other hour, or no time at all. But it wasn’t too bad, and it didn’t take long to adjust to the frantic schedule. I spent much time gaming, often when wearing my kiddo - baby wearing is the best: hands are free, but we both are getting the cuddles.

I’ve spent much time building adorable villages and towns in Foundation, ran around as a little crow in Death’s Door, smote enemies of humankind in Total War: Warhammer, kicked off another playthrough of Dread Delusion, and casually tortured the unfortunate inhabitants of Rimworld.

Having a newborn taught me a lot about resilience. I can get interrupted any time. Some days my kiddo’s having a great day - sleeping like a baby (did you know that babies are very noisy sleepers?), playful, and all around a delight. And some days my potato would wake up, fart angrily, and choose a path of violence. The day has a tendency to disappear when that happens. I just learn to accept when things happen - it’s a quality I had in my early twenties, but it’s a part of me I lost as I’ve gotten older, more comfortable, more set in my ways, and more used to things going exactly my way (I’m sure you picked up on that). Well you can’t negotiate with a baby, they’re like a little terrorist in that way.

After nearly a month of non-stop gaming, I decided to get my affairs in order. I scanned a built-up stack of documents, kicked off trust paperwork I’ve been sitting on for months, did my taxes, organized my Vimwiki, cleaned out my inbox, spring cleaned the house, went through needed repairs… It was nice to get everything in order, but the time just started to get away from me. All the chores just started feeling like… a job? Ugh.

A retired colleague of mine once said that in retirement it’s very easy to lose yourself in chores and busywork. In these three months of my mini-retirement, and I saw myself fall into that trap - there’s always something to do - something to clean, something to organize, and something to do. I find myself easily getting obsessed with things, so if I decide to tag and date all my scanned documents, I can wave the next four days goodbye.

After my organization kick, I started getting back into hobbies. Now to you these hobbies might just look like another chore, but I truly enjoy those things - I might be just a little bit boring. I cleaned up my blog and got back into writing. I got our household financial projections and budgets in order. I finally went back to my neighborhood jiu jitsu dojo - oh how I missed the community (and exercise, of course)!

Then I started playing around with setting up a home server. I don’t get to code much at my job these days, being a manager and all. All my interactions with technology are either through documents, presentations, spreadsheets, and meetings - oh-so-many-meetings. While I really enjoy that I get to do much more than I could by myself (leveraging the power of half a dozen engineers, that is), none of it feels as satisfying - I didn’t really build this cool thing with my own hands, and my contributions are gently spread out here and there.

So, I spent a few weeks setting up a local home server - refreshing my knowledge of networking, getting familiar with Docker, tinkering with software and firmware. I even got to tinker with AI tooling. Being a know-it-all software engineer, I played around with early AI models last year, and they were terrible. Well, the same former colleague wrote an opinion piece on how much better AI models have gotten. And boy-oh-boy was he right. I had to play a lot of catch-up, but it was interesting (albeit weird) discovering how to get debugging help from an AI chatbot.

For the first time in years, I got to directly engage with fun tech, and I got to use my hands (on a keyboard) to make something that, despite all odds, works. I’ve forgotten how much I like tinkering with stuff, and how much bossing people around and being the organizational connective tissue is a step away from that. I’ve pretty much forgotten why I started in tech to begin with.

And that’s where I am now. Three months into taking time off to care for my newborn, ending up with lots of time for self-discovery, hobbies, and chores. Working through this period would’ve been a nightmare (yeah, my schedule wasn’t really my own), and I’m grateful for the opportunity to spend time at home.

Well, not working is amazing. Not for a minute did I find myself bored. Yes, having a little one to take care of definitely helps to keep me busy, but, courtesy of my loving wife, I’ve had a lot of time to myself. And it’s been amazing. No shit, Sherlock, did I just discover that not working is better than working? You wouldn’t believe how common the toxic notion of “I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I didn’t have my career” is in the industry. It’s nuts. And it’s nice to know in practice it doesn’t apply to me, at least in this three month mini-retirement stretch. Or maybe I’m just burnt out at my job, who knows.

I recognize that things will change - once my newborn becomes a toddler I won’t have the same type of free time, and I’d have to figure out ways to incorporate my toddler into my interests - or my interests into my toddler. But I’m excited for that chapter.

-

My experience with minimalism

Minimalism was always appealing to me. The philosophy of not having more than one would need is close to my heart. Over the past few years, I’ve been “trimming the fat” off various parts of my life.

I can’t recall when I started being drawn to a minimalistic lifestyle. I think my passion for minimalism originates in my desire for organization and order. It’s comforting to know that a world around me has a certain structure.

I remember the time when I started living on my own. I just moved to United States, away from my family. All my life fit in a half-empty suitcase at that time. Few sets of clothes, a blanket, a pillow, some hygiene products, a small laptop. Moving to a new place was as easy as throwing few things in that suitcase.

After some time, I started accumulating more things. A guitar. More variations of clothing. Cheap coffee table and a shoe rack from a dollar store. At that time I rented a room in one of the shady areas of the city. Adding a few pieces of furniture made a place feel like home.

Time has passed, and I moved again. Left the furniture behind, took the rest. Still light, but I did have to make a few trips to move everything I needed. I got even more comfortable. A gaming PC. Significantly more junk here and there.

That’s when I did my first big cleanup. I went through every item I owned, and tossed it a trash bag if I didn’t use it in the past 6 month. Old clothes, some action figures, other useless junk I accumulated. As a result, I tossed two big bags of stuff I didn’t need. I still remember the liberating feeling. Knowing that everything I own serves a purpose.

It felt like I could breathe again.

Years pass. I don’t rent rooms anymore, but apartments, houses. This comes with having to own more things. Real furniture. A TV. More musical instruments. Having to accommodate guests. Cooking supplies. A bike. Outdoor furniture.

But I’ve kept the minimalistic mindset, and I still do periodical clean outs. Tossing almost everything I haven’t used in a past six months. Reducing what I own only to things that I need to have comfortable and enjoyable living.

Today, I don’t think I can fit everything I own in that single suitcase. Hell, I most certainly will need to hire a truck for my next move. But that’s not important. Minimalism isn’t about the absence of things. If you feel like you don’t have enough - you’re probably doing something wrong. Minimalism is about not being excessive.

For me, knowing that my belongings serve a purpose makes me feel content, clear-headed. It’s comforting. It feels right.

Sometimes, I forget and start accumulating stuff. And that’s when I go back to reducing again. It’s not an obsession, but a healthy periodical maintenance. Often it takes months, or even years to get rid of certain things.

Replace a queen sized bed with a Japanese futon mat. Digitalize the growing paper trail I keep. Travel the world for with a single suitcase.