Category: Work

Subscribe via

RSS

.

RSS

.

-

Brainstorming terrible ideas in a group

Years ago a colleague of mine taught me a brainstorming technique that I find particularly useful. Thanks, Meagan.

Here’s the thing. Often, when brainstorming in a group, even with a good degree of psychological safety, participants are often worried about appearing like idiots, or having bad ideas. There’s a reputation to maintain after all, and we’re all taught to think before we speak. I find this group brainstorming method to be useful to get around this mental block.

You create four buckets for solutions to a problem:

- Ideal: If I had a long time horizon to solve this problem

- Realistic: If I had limited time and resources

- Wasteful: If I didn’t care about time and resources at all

- Harmful: If I wanted to sabotage the problem

And participants are tasked with populating each bucket. Here’s the fun part: actively harmful and wasteful solutions often lead to the best outcomes.

Let’s walk through the example. Say you have a team wiki that’s neglected and out-of-date. You’re trying to figure out how to solve this problem. Here are the ideas:

- Ideal: Hire technical writers to constantly audit and rewrite the documentation.

- Realistic: Implement a mandatory wiki cleanup day, where each team member is assigned a portion of the wiki to update.

- Wasteful: Award $500 to whoever contributed the most pages to the wiki each year.

- Harmful: Set content to self-destruct after 3 months. If the content is important, someone will write it again.

All of these ideas have problems. Technical writers will not have the context and could put undue communication burden on the team, company mandates are never fun, encouraging quantity of contribution can lead to decrease in quality, and deleting the data defeats the purpose of having a wiki in the first place.

But this gets you thinking - maybe the harmful idea isn’t so harmful after all. Maybe a staleness banner on pages, with a name of the last editor and a nudge to them could help keep the wiki up-to-date.

In my experience, “Wasteful” and “Harmful” buckets have a disproportionate number of responses, many of which start as jokes (“fire everyone”, “reboot every 5 minutes”, “use carrier pigeons”), and improve upon iterations into the winning ideas.

-

On corporate jobs and self-worth

As someone who works at a large corporation - Google - and someone who always thought working at Google would be really cool, I put a lot of my self-worth into my job. When things go well at work - I’m doing well. When they’re going awry - my well-being follows.

Yeah, that’s not a very healthy take, and I know it, but as someone who’s been in the tech industry for the past 14 years, it’s a difficult worldview to escape. At this point it’s probably a deep seated core belief.

A close friend of mine is leaving Google this week. She’s taking a voluntary exit program, which is effectively a more humane way for a large company to organize workforce reductions. It’s better than the layoffs we’ve also seen quite a few of lately. After being a model employee for the past decade, she’s leaving the company (and tech in general) to focus her passions elsewhere. She’s excited for the future ahead, and she’s lost too, and I think I would be too.

It’s understandable - humans are wired to want to provide some social value. You want to be working for the good of the tribe, and you want the tribe to see and recognize that. Moochers will be shunned, and in the olden days being shunned would spell certain death. People usually can only survive together, in a group.

But in a modern world, it’s remarkably hard to connect the value of the work you do to a greater whole, to the goodness of your tribe.

I had a short opportunity to not be in the workforce for 3 months as I took my paternity leave. I didn’t experience a sense of decreased self-worth, but many other factors were in play. Naturally, my daughter was born and it was exciting, and so many things were happening. Figuring out how to parent a newborn isn’t easy and doesn’t leave much room for existential crises. But there’s also a lot of social value to being a dad and raising a child, which felt extremely gratifying. I imagine if I were to just take extended time off without a purpose like that one - I wouldn’t be as satisfied, and I’d begin to question my own self-worth.

I’ve been an aspirational FIRE practitioner for over a decade. FIRE stands for Financial Independence Retire Early - a terrible acronym, but the idea behind it is solid: reduce expenses, increase income, invest the difference. Many FIRE practitioners retire in their 30s or 40s, but I’m not quite there, and I enjoy aspects of work (and paycheck doesn’t hurt, either). What I like about FIRE as a philosophy is that it forces me to confront what it’s like to not have to work. That’s the end goal after all, but hearing from my retired friends, it always sounds like you just replace old problems with new ones.

In the end, I feel like it all comes down to finding things to value about myself that are outside of the job. I’m learning that it’s all about moderation. I’m trying to find a way to balance the different parts of my life, so that no single aspect, like my career, outweighs all the others. Because I feel like when I put all my self-worth eggs in one basket, it’s not a question of if things will break, but when.

-

Reflections on my paternity leave

Google provides generous parental leave, and I’ve been able to take three months to spend at home with my newborn. I even have some more time I can take once my wife returns to work! For residents of the Land of the Free, it’s a lovely glimpse into having a social support net and worker protection. Could you imagine?

And let me tell you, not working for three months was really nice. My newborn arrived a bit early, so the start of my leave was frantic - one Friday evening my wife said she was feeling off, we went to a hospital, and by the next morning my kiddo was born. I didn’t get much chance to wrap things up at work, but with the newborn here I didn’t particularly care. Three months into my leave, I still don’t care, and it’s nice. I’m sure I won’t be able to keep not caring for long once I’m back at work though.

My kiddo spent the first week in NICU (for those of you without much trauma in life - that’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), and once the danger had passed, it was a positive experience. The nurses were knowledgeable, and it was nice having “world’s best paid babysitters” keeping an eye on my baby 24/7. While my wife was recovering I spent most of the time with the kiddo - and turns out having a kiddo comes with a lot of downtime. I booted up my trusty Nintendo Switch, loaded Skyrim for the umpteenth time, and spent hours day and night gaming away while my kiddo was asleep on my chest. Man, newborns sleep a lot.

The kiddo started gaining weight, and we were ready to be discharged. Before being sent home we even managed to sneak away to a restaurant and celebrate our little victory! It’s been a long and perilous journey for our family, and it was a lovely opportunity to connect while the NICU nurses kept our tiny one safe. Although we were sent home without adult supervision, how dare they?! NICU bootcamp was tremendously helpful, and after the first couple of sleepless nights, we started figuring things out. That’s when this whole leave started feeling like a retirement preview, in a good way.

I wouldn’t consider myself a workaholic. I generally try to keep my work to under 40 hours a week, and I make sure to disconnect from work. I tend to give my work 110% while I am at work, which does tend to have a negative effect on me when things don’t go my way - that’s when my hours slip, and my ability to fully disconnect crumbles. I’m only human after all.

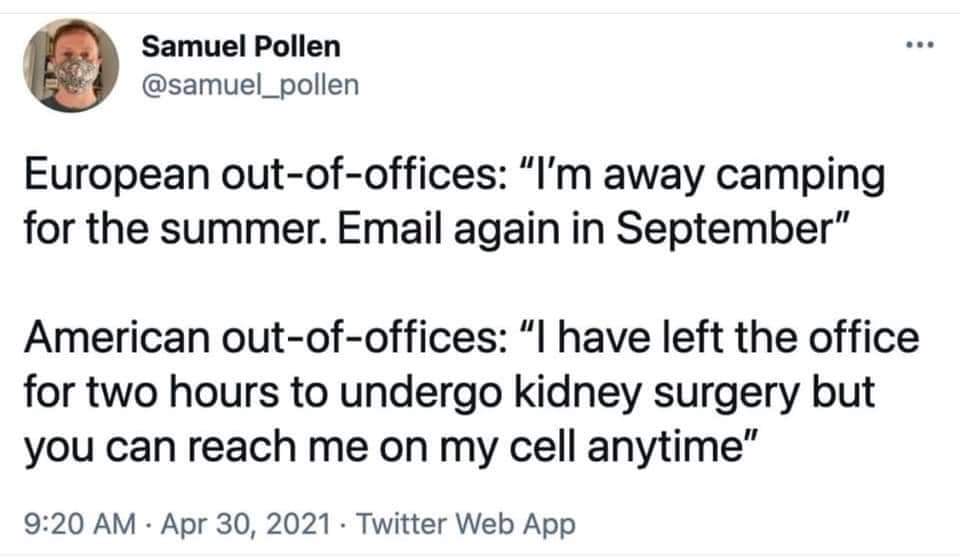

And I don’t take nearly enough vacation. I have generous vacation days (although nothing compared to how much our European colleagues get), but I think the American corporate culture has a hold on me. There’s a major sense of FOMO, and it feels like there’s never a good time to disconnect. There’s a lot of pressure to continue working towards the next milestone, next project, next promotion - “I’ll take time off after that”. And I just never do.

My wife and I manage occasional trips, but anything longer than a week is rare and stands out, and I often get nudged by corp systems “Take your vacation days or they’ll disappear” (ugh, why don’t you pay me the difference instead?).

All that to say, in nearly 15 years I’ve been in the workforce, I’ve never been off work for this long. And as someone who’s been glorifying early retirement and saving away for a rainy day for a decade now, this leave started to feel like an early retirement trial run. And I loved it!

Now, back to bringing our baby home: after settling into life, I started having lots of free time. It was a different kind of free time - there was lots of it, but none of it was on my schedule. If my partner felt generous, I might get nearly a full day to myself, or an hour every other hour, or no time at all. But it wasn’t too bad, and it didn’t take long to adjust to the frantic schedule. I spent much time gaming, often when wearing my kiddo - baby wearing is the best: hands are free, but we both are getting the cuddles.

I’ve spent much time building adorable villages and towns in Foundation, ran around as a little crow in Death’s Door, smote enemies of humankind in Total War: Warhammer, kicked off another playthrough of Dread Delusion, and casually tortured the unfortunate inhabitants of Rimworld.

Having a newborn taught me a lot about resilience. I can get interrupted any time. Some days my kiddo’s having a great day - sleeping like a baby (did you know that babies are very noisy sleepers?), playful, and all around a delight. And some days my potato would wake up, fart angrily, and choose a path of violence. The day has a tendency to disappear when that happens. I just learn to accept when things happen - it’s a quality I had in my early twenties, but it’s a part of me I lost as I’ve gotten older, more comfortable, more set in my ways, and more used to things going exactly my way (I’m sure you picked up on that). Well you can’t negotiate with a baby, they’re like a little terrorist in that way.

After nearly a month of non-stop gaming, I decided to get my affairs in order. I scanned a built-up stack of documents, kicked off trust paperwork I’ve been sitting on for months, did my taxes, organized my Vimwiki, cleaned out my inbox, spring cleaned the house, went through needed repairs… It was nice to get everything in order, but the time just started to get away from me. All the chores just started feeling like… a job? Ugh.

A retired colleague of mine once said that in retirement it’s very easy to lose yourself in chores and busywork. In these three months of my mini-retirement, and I saw myself fall into that trap - there’s always something to do - something to clean, something to organize, and something to do. I find myself easily getting obsessed with things, so if I decide to tag and date all my scanned documents, I can wave the next four days goodbye.

After my organization kick, I started getting back into hobbies. Now to you these hobbies might just look like another chore, but I truly enjoy those things - I might be just a little bit boring. I cleaned up my blog and got back into writing. I got our household financial projections and budgets in order. I finally went back to my neighborhood jiu jitsu dojo - oh how I missed the community (and exercise, of course)!

Then I started playing around with setting up a home server. I don’t get to code much at my job these days, being a manager and all. All my interactions with technology are either through documents, presentations, spreadsheets, and meetings - oh-so-many-meetings. While I really enjoy that I get to do much more than I could by myself (leveraging the power of half a dozen engineers, that is), none of it feels as satisfying - I didn’t really build this cool thing with my own hands, and my contributions are gently spread out here and there.

So, I spent a few weeks setting up a local home server - refreshing my knowledge of networking, getting familiar with Docker, tinkering with software and firmware. I even got to tinker with AI tooling. Being a know-it-all software engineer, I played around with early AI models last year, and they were terrible. Well, the same former colleague wrote an opinion piece on how much better AI models have gotten. And boy-oh-boy was he right. I had to play a lot of catch-up, but it was interesting (albeit weird) discovering how to get debugging help from an AI chatbot.

For the first time in years, I got to directly engage with fun tech, and I got to use my hands (on a keyboard) to make something that, despite all odds, works. I’ve forgotten how much I like tinkering with stuff, and how much bossing people around and being the organizational connective tissue is a step away from that. I’ve pretty much forgotten why I started in tech to begin with.

And that’s where I am now. Three months into taking time off to care for my newborn, ending up with lots of time for self-discovery, hobbies, and chores. Working through this period would’ve been a nightmare (yeah, my schedule wasn’t really my own), and I’m grateful for the opportunity to spend time at home.

Well, not working is amazing. Not for a minute did I find myself bored. Yes, having a little one to take care of definitely helps to keep me busy, but, courtesy of my loving wife, I’ve had a lot of time to myself. And it’s been amazing. No shit, Sherlock, did I just discover that not working is better than working? You wouldn’t believe how common the toxic notion of “I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I didn’t have my career” is in the industry. It’s nuts. And it’s nice to know in practice it doesn’t apply to me, at least in this three month mini-retirement stretch. Or maybe I’m just burnt out at my job, who knows.

I recognize that things will change - once my newborn becomes a toddler I won’t have the same type of free time, and I’d have to figure out ways to incorporate my toddler into my interests - or my interests into my toddler. But I’m excited for that chapter.

-

Essentialism: A Practical Guide to Less

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed Essentialism, a book that encapsulates the simple yet powerful notion of “do fewer things, do them well.” There’s not much else to it. While this philosophy is straightforward, it’s the way Greg McKeown presents and reinforces this message that makes the book truly compelling.

Having Essentialism in physical form proved invaluable. I filled the margins with notes, worked through exercises alongside the text, and took the time to fully absorb the material as I progressed.

Essentialism is not a new concept, but the key takeaway is the author’s focus on truly internalizing the message. “Focus on things that matter, trim the excess” is a simple motto to remember, yet challenging to implement. Throughout my life, I’ve adopted many of essentialist practices in one form or another, from guarding my calendar to learning to say “no” to prioritizing essential projects. However, over time, clutter inevitably creeps in.

McKeown wisely focuses on routines that support the essentialist lifestyle, emphasizing the importance of dedicated time for reevaluation and recentering. He suggests establishing routines that prevent slipping into the frantic “onto the next thing” mentality so prevalent in the modern corporate world.

An analogy that particularly resonated with me is the closet metaphor. While you can declutter your closet once, it will eventually refill with clothes you don’t need. To keep your closet tidy, you need to have a regular time to reevauate your outfits, know where the nearest donation center is, how to get there, and what hours is it open. Similarly, McKeown provides methodologies to regularly reevaluate our priorities, supporting the rigorous process of regularly discarding the non-essential.

Essentialism extensively focuses on routines, practices, and exercises. The edition I read includes a “21-day Essentialism Challenge,” a helpful list of concrete activities corresponding to each chapter. While some prompts, like “take a nap” or “play with a child for 10 minutes” are a bit silly (where am I supposed to find a child on a Tuesday, Greg?), many steps effectively reinforce and integrate the material into your daily life, such as “design your ideal calendar,” “practice saying no gracefully,” or “schedule a personal offsite.”

The latter suggestion, scheduling a personal offsite, left a significant impression on me. It’s time dedicated to strategizing around your personal and professional goals. While I occasionally reflect on my career and life, McKeown elevates this practice into a ritual – a full day focused on self-reflection, planning, and deliberate action.

Essentialism is a helfpul book that prompts the reader to think about the routines one can put in place to change the way we approach life. It’s a reminder that less can indeed be more, and that by focusing on what truly matters, we can create a life of greater purpose, meaning, and fulfillment.

-

The Eisenhower matrix

The Eisenhower matrix, sometimes known as the priority matrix, is an invaluable planning tool, and something I have been consistently using for the better part of the last decade.

As someone who has a short attention span and easily gets overwhelmed, I find Eisenhower matrix to be an invaluable tool in allowing me to focus on what’s important, rather than what’s right in front of me.

Oh, I still struggle to make sure that things that are important to me are what matters to others, but that’s a whole different battle - at the very least I’m able to keep my own head straight, and that’s a win in my book.

Without any further ado, I present to you the decision making framework developed and popularized by Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 34th president of the United States (and clearly a notorious efficiency nut).

It’s pretty simple, really. Take everything from your long single-file To-Do list, and place it on the matrix based on its urgency and importance. Work through the matrix in the following order:

- Urgent and important: get these done, now.

- Important, but not urgent: decide when you want to do these, actively make time for yourself to work on those.

- Urgent, but not important: delegate (read on below if you have no one to delegate to).

- Not urgent and not important: take time to eliminate these tasks.

Do now: a common pitfall

It’s easy to throw everything into the “urgent and important” pile. In reality, that’s not often the case. If you find yourself throwing everything in the first quadrant - I implore you to think of your tasks in relative terms. Out of everything on your mind, I’m sure some things are more important than others.

I find that over time most of my work shifts into a single quadrant (usually the “important, but not urgent”), and I find it helpful to redistribute those, or populate the matrix from scratch.

Schedule: mindful use of time

One of the goals of the Eisenhower Matrix is to increase visibility into how you spend your time. While it’s easy to spend most of the time in the “urgent and important” quadrant, the best work happens in the “important, but not urgent” section of the matrix. That’s where the best use of your time is, and that’s where most of the energy and attention should be spent.

Otherwise you’re just running around like a chicken with its head cut off, although I can sympathise with the difficulty of getting out of the urgency trap. It’s not trivial, and probably downright impossible in some cases.

This is where the biggest pitfall of the Eisenhower matrix lays in my experience. You want to maximize amount of time spent in the “schedule” quadrant, but you don’t want to end up with a massive list that becomes a yet another To Do list, because one dimensional To-Do lists suck.

Delegate: to whom?

Not everyone has someone to delegate work to. Or not everything can be delegated. In these cases, I treat the “delegate” bucket the same as “eliminate”. Hopefully that won’t come back to bite me in the future.

Eliminate: it’s hard

I really like following up on things, to a fault. I don’t like leaving loose ends, unanswered emails, or unspoken expectations. I find it helpful to schedule time to explicitly eliminate certain work, and communicate explicit expectations to everyone around me about that. Because of that, that’s where the most of my procrastination happens. Telling people “no” isn’t always easy, and I still don’t have the best process for combing through the “Eliminate” quadrant.

I know many people are a lot more comfortable letting unimportant things quietly fall through the cracks, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

-

High stakes email checklist

I’m making a little cheat sheet for myself. As I progress in my career, much of my work revolves around communication, and I’d be remiss if I don’t share a formal framework I use. I like checklists, spreadsheets, and anything else that organizes the world around me, and it’s fun to make one about communications.

Checklist

This is a checklist for high stakes emails, let’s dig in:

- Goals

- What are you trying to accomplish? Why? (It could be worth asking why multiple times.)

- Will this email help you accomplish the goal?

- Can the goal be summarized in a single sentence? If not, it’s probably not specific enough.

- Audience

- Who is the audience?

- What does the audience care about? How can you connect the subject of your email to things they care about?

- Does every recipient need to be there? Who’s missing?

- What action do you want the reader to take? Is there a clear call for action? For executive communications (who have notoriously short attention span), you’ll want to both start and end with the same call for action.

- Content

- Is there a nuance that would be lost in email that requires face to face conversation? Does this need to be an email?

- Does every sentence and paragraph support your goal?

- Does this need a TL;DR?

- Is the narrative structure in place? Is there a clear beginning, middle, and end? No need to write a novel, but without this the content risks being disjoined.

- Impulse

- Is now the best time to send it? Friday afternoon is almost always a no-no, unless you purposely want the reader to pay less attention to the issue.

- If this was shared broadly, would you rephrase it? If yes - you definitely

should.

- To double down, if email is about someone, write as if that someone will eventually see it. It’s fine to be candid, it’s not fine to be rude.

- Are you angry? Upset? I get notoriously cranky in the late afternoon, and avoid sending anything important until the next day - or, if time sensitive, until taking a short break or a walk.

Example

Let’s apply this to an example. Say, I’m writing a book, and the editor I’m working with hasn’t been responsive. I’ve tried talking to them about it, but they’re not responsive. I think it’s the time to escalate to their supervisor.

Here’s the quick, dirty, and impulsive draft I would write:

Hello X,

Y hasn’t been responsive when reviewing the chapters, and it’s really difficult to get back to chapters after a whole week passes by. By then I don’t even have the context! I’ve raised this multiple times and to no avail. Can you please get Y to be more responsive or find another editor for me to work with? I haven’t been able to make meaningful progress in a month!

Pretty brusque, isn’t it? I don’t normally dissect every email like this, but sometimes it helps to take a closer look and formalize the decision making behind each sentence. Thankfully, much of this becomes habitual over time.

Goals

First things first, I want the editor to be more responsive. Why? To have a shorter feedback loop when it comes to making changes. Why? To make it easier to write - it’s difficult to come back to the chapter after a long amount of time passed. Why? This pushes back timelines for each chapter.

I don’t really care about how to achieve this goal: the same person can be more responsive, or maybe I get a new point of contact to work with. Maybe there are other options I haven’t considered.

To summarize in a single sentence, the goal is to “reduce the feedback loop”.

Audience

The audience is the editor’s supervisor, or maybe someone else from the editorial team who’ll have the incentive to escalate.

I know that the timelines are very important to this publisher, which is something I can use. I can frame the concerns around impacts of the timeline - even if it’s not something I necessarily care about myself.

Since there are multiple ways to achieve my goal and I don’t particularly care about how, I can make the call for action open ended. I’m doing this because I’m comfortable with either outcomes - like the editor not being to improve response times, but the publisher providing more leniency around the schedule - which, while isn’t ideal, still helps.

Content

As multiple people can help me accomplish a goal, and I might not be aware of all of relevant parties - email format works best.

Narrative structure here is simple - I have a problem (the beginning), here’s why it’s bad (the middle), let’s fix it (the end).

This email is short enough not to require a TL;DR.

Impulse

As my concern is about a particular person, I have to talk about them. I don’t want to avoid candor, but I can approach the situation with empathy and assumption of best intentions something along the lines of: “I understand X has other commitments”. Focusing on facts and leading with empathy would help here.

Having an unresponsive editor is definitely frustrating, so it’s worth taking a step back, and maybe paying extra attention - there’s no use having frustration show through.

The result

After running through the checklist, we end up with (what I hope is) a better, more actionable, and less icky email:

Hello X,

When working with Y, it takes up to a week for me to receive feedback on the chapters I wrote. I understand Y is working with multiple engagements, but I’m concerned about the timelines for the book. If we continue as is, it’s likely we’ll have to push publishing date by X months.

Could you help me find a resolution here?

It’s short, omits unnecessary details, and leaves the reader with a clear (but open ended) call for action. Now, all that’s left is to schedule send that email in a morning, and wait for a response!

- Goals

-

Journaling for work-life balance

When writing about snippets at Google earlier this week, I omitted a fairly important bit: how lists and journaling help me create distance between work and life. This became especially relevant in the pandemic, as I had to work with my therapist on being able to mentally disconnect.

I wrote about my strained relationship with ToDo lists before: all the way back in 2014. Back then I focused on moving away from a monolithic ToDo list, and focusing on just a few major things I’d like to accomplish each day. I continued to do this, but with some changes to my philosophy.

I’m back to keeping a ToDo list, but it’s a bit more complex than a single list I used to keep. I split things I care about by days, weeks, and months, and I review these lists regularly.

Last year I learned about bullet journaling, often shortened to “BuJo”. Akin to artisan coffee and avocado toast, this hipster friendly and highly marketable approach has a solid foundation. At its core bullet journaling consists of two parts. First is a consistent and simple notation for tasks, notes, and events: some simple guidelines on how to document what happened, what will happen, and what you need to remember. Second part is a rule set on organizing these lists: daily and monthly notes, custom logs, and so on.

I rigorously keep daily notes about work, meeting annotations, records of important thoughts and ideas, and things I need to do (or have already done). This helps me leave work at work – or more precisely leave work in a journal. Once it’s closed - I’m done for the day. Everything I need to think about is written down, and there’s no need for my mind to wonder back.

Some weeks I omit note taking, and the contrast in my well-being is jarring. My mind wonders back to the events of the week, and I even have trouble sleeping some days. And no one wants to dream about work – I’m sure as hell not paid enough for that.

Another technique I picked up from the bullet journal keeps me from getting overwhelmed and keeping focus. BuJo advocates for regular migration of ToDo items – meaning that you should be crossing out and rewriting the same thing over and over again, day by day, week by week. At some point it becomes either to either do something about those ToDos, or choose not to do them altogether. Either way, it’s a huge weight off my shoulders.

And this is where the aforementioned snippets come in. At the end of the week, all I have to do is go through the weekly set of notes, and transcribe noteworthy bullet points. That’s the time I take to look back at my week, migrate tasks I choose to revisit at a later date, or cross off tasks I choose not to do.

-

Communicating via snippets

I’ve learned a lot of cool things during my tenure at Google.

One of those things are snippets. Google (and from what I hear other Silicon Valley giants as well) utilizes a system of snippets: a transparent and widely accessible set of weekly notes. It’s not mandatory, and some groups use it more often then others. Sounds ordinary, but I think it’s a lot more interesting then that.

Communication and visibility is one of the major challenges in any paid creative work, but it’s especially important in software engineering. Engineers often settle on tasks they know nothing about: tasks are hard to measure and estimate. This makes it even harder to communicate progress broadly.

There are ways around this communication barrier – regular standups or periodic reviews come to mind. But there’s a better (although not necessarily exclusive), more asynchronous way to communicate and increase visibility. Enter snippets - a condensed list of what happened with you and your colleagues last week, delivered straight to your inbox.

Every Friday, an email notification reminds you to fill in weekly snippets. These snippets might look something like this:

- Project X

- Authored a design doc (link), sent for a review

- Discussed roadmap with stakeholders A and B (notes)

- Debugged issue Z, to no avail (link)

- Project Y

- Cleared backlog for the past 6 months

- Attended a summit about G

- Had 1:1s with C, D, E, and F

On Monday, an email goes out compiling our team’s snippets in a single digest. Skimming through snippets covers any communication gaps from the past week, and raises visibility on what everyone is working on.

This system has many benefits:

- Transparency: you know what everyone around you (including higher ups) is up to.

- You actually remember what you’ve done a month from now.

- All the important documents, events, and notes are linked from snippets. Snippets are are time bound, which makes these documents easy to find.

- Teammates and managers can always check snippets to get an idea of progress on certain efforts.

- You manager (who’s hopefully your biggest ally when it comes to career development) has a great idea of what you’re up to.

- It’s easy to find artifacts and proof during performance reviews.

- Higher visibility of glue work (all the little things you do to keep the place running).

This doesn’t have to be a particularly complex system. A running doc with notes could suffice, although email notifications remove a lot of the overhead needed. Even if the organization doesn’t follow the model, I find it worthwhile to keep snippets, and to share them with my manager and team.

- Project X

-

Living at work

My first remote work experience coincided with my self-employment as a contractor. I was building a copyright enforcement service for a client in a year 2013. I lived in a one bedroom apartment in Philadelphia with my now ex-wife – a few blocks away from the city hall. I worked at a small standing desk (trendy!) in a corner of our little bedroom - by the closet.

I worked from the early morning and deep into the night at that desk. Sometimes I would look out of the window behind me. I would see an uninspired urban picture of roof tops of other four story colonial homes. And after a moment of respite it was back to work for me.

This was my first major foray into the world of self-accountability: I meticulously tracked the time spent working, billed the client per hour, provided in-depth breakdowns. The more I worked, the more I could bill the client – I had the incentive to put in as much time into work as possible.

So I did. I clocked in 80 to 90 hours of billable time a week. The checks with a before unheard of hourly rate kept coming, so I kept putting in the hours. Neither I nor my significant other had major professional experience. (To be completely honest we didn’t have much in the realm of like experience either). We kept on keeping on.

I thought about work during lunch. I was agonizing over the details when walking through the neighboring Rittenhouse Square. I would jump into late night coding sessions. As a young professional, I didn’t see the need to draw lines between my work and my life – my life was my work. There was no “me” without work.

That is until I burnt out. I woke up one morning, and something inside me snapped. I realized that I couldn’t spend another minute in front of the screen. I took a day off, and the feeling wouldn’t pass. I felt numb and overwhelmed at the same time. A day filled with my favorite video games - and I still felt that way. A day at a museum - nothing. I didn’t get better.

I invoked a force majeure clause in my contract. I transferred all the materials, sent the final invoice, and stepped away from the project.

I won’t talk here about the ways to fight burnout, because I didn’t know how to. I quit, took a break, and eventually moved onto another job. By the virtue of this happening early in my career, and me being rather young - I managed to “snap out of it” between jobs.

I wish I could share “the one thing” I did that helped - but there wasn’t one. I don’t remember how I took care of myself, and how I managed to get my head straight. All I remember that I felt discombobulated for weeks. And at some point the feeling went away. I couldn’t work during that time.

Time passed. I moved across the country to the San Francisco Bay area for a job with Google. My now ex-wife and I split up – it was a civil, but nonetheless a difficult divorce.

Around that time, I spent a year traveling across the United States. I lived out of my car and stayed in hotels while working remotely on my own terms. I established strict working hours and routines.

I would start my work around 8 am, without paying mind to the timezone I’d be in. I’d work out of coffee shops, coworking spaces, or even campgrounds. I’d always take a break for lunch. I’d wrap up work at 4 pm, and not a minute longer. Constant travel and change of scenery encouraged me to keep to my work hours. I had to weigh in staying past my end of workday versus going out and sight seeing a new city. The wanderlust always won.

The work was out of my mind after 4 pm. That was easy to do with an adventure afoot, but years later and the habit stuck with me. I don’t let thoughts about work slip into my day to day. My mind is my own outside of work.

That was a transformative experience, and it changed the way I see work. I know it’s trendy to say this, but I don’t live to work: I work to live.

Today, I work with some people who have never worked remotely before the pandemic. And I often hear a similar sounding sentiment: “never again”.

It makes me think about the time I was self-employed for the first time. Putting in 80 hour work weeks, and not having the awareness to understand how I was affecting myself and people around me. It created distance between me and my partner. I let the work spill into the time I had. In a way it made me less of an employee and less of person.

When the pandemic started I looked back to these memories. Google moved to continuous work from home model in March 2020. And I made a conscious effort not to slip into my early remote work days. I established a strict routine. Breakfast and lunch with my significant other (here’s some closure to my divorce). No deviation from “9 to 5”.

I established an area for myself to work in – I bought a sturdy desk and a chair from a used office furniture reseller. I make an effort to create not only mental, but physical separation from work. I wear office clothes during the day, and change once I’m done with work. I cook to distress after a long day. My partner and I adhere to scheduled date nights (we do leave room for spontaneity too).

That isn’t to say I didn’t slip over the past year: many times I stayed past an established time. I often started earlier than planned. And some days I would let work occupy my mind space as I’m relaxing with my better half. We’ve spent the past year working out of a one bedroom apartment. A bigger one than I worked out of 7 years ago, but still a one bedroom. It was difficult, and some days it still is.

But time and time again, I corrected the course and resumed my routine. During my soul searching adventure remote work was fun. Because this time working remotely is much harder. There are no sights to see. No new places to stay in. No novelty to look towards at the end of the day. Working from home in the middle of a pandemic is oh-so-difficult.

To be honest I can’t wait to be back in the office. But I’m also excited to work from home on my own terms. Because this isn’t what remote work is like.

-

The feedback fallacy

After learning about “Radical Candor”, I became obsessed with providing candid and compassionate feedback. I’ve been especially focused on the ability to communicate areas of growth for individual on my team.

And then a colleague of mine shared “The Feedback Fallacy” (published in the Harvard Business Review), which points to some research and outlines a few key problems why focusing on negative feedback might not be the best choice. Research shows that:

- people are bad at assessing other people

- we learn best with positive reinforcement

- focusing on shortcomings impairs learning

- excellence is specific to an individual

Like many pieces of business literature, it reads like an “all-or-nothing” approach (“negative feedback - bad, positive feedback - good”), and the most effective approach is likely somewhere in the middle. There’s a place for positive and negative feedback, and it’s the focus on positive reinforcement that I see as a primary takeaway from this article.

I’ve noticed that my assessment of others’ performance changes over time. It often depends on what self-help book I’m reading at the moment if I’m being entirely honest.

This piece made me think of the portrayal of successful people in media: there’s an inherent cultural belief that successful people know what makes them successful, and all you need to do is to follow in their steps! What is often omitted is a mix of luck, some talent or hard work, topped with another serving of being in the right place at the right time. Warren Buffet can probably tell you what’s the smartest thing to do with ten thousand dollars you have in your savings account. It’s unlikely that his advice alone will get you to his 98.2 billion dollar net worth.

It seems like once you get past basic competency, success identifiers seem unpredictable.

I attribute part of my professional success to having a reputation of a person who “gets shit done”. I naturally value qualities associated with that style of work. It’s only natural that I prioritize on communication and organizational skills when assessing the performance of others.

In fact, the article made me think about how I landed with the reputation as a problem solver. Every time I accomplished a project on time, owned the problem space, involved the right parties, or raised alarms early – I received positive reinforcement. People I worked with valued those qualities, and years working with those people shaped what I perceive as an effective work style.

Yet, this work style is effective for me, and is not a solution for my peers.

Since reading “The Feedback Fallacy”, I started focusing on the outcomes I like, as opposed to qualities I believe are valuable. Where before I would say “Great comms on project X!”, now I focus on specifics: “I know what you’re up to on project X, which helps me communicate with stakeholder Y and plan resources for the project Z”

-

Take a pause before that email

I’m not an ill tempered person, and it takes quite a lot to get me riled up. In the pandemic however getting frustrated has been oh so much easier!

For once, there are less face to face interactions, which makes me feel removed from whomever I’m talking to. The interactions that happen over video chat feel a lot less personal, and despite regular deliberately scheduled 1:1 time it’s harder to connect with colleagues on a personal level.

Then there’s the lack of water cooler interactions between meetings. A colleague of mine correctly pointed out that before the era of video chat meetings, we’d have the time to decompress and process content between meetings with those micro-interactions. Having just a minute or two “off the record” after a large call helps process, frame, and align prior interaction. And just sharing a laugh or being able to say “well that was stressful” helps reduce the inevitable daily stress buildup.

Finally, all of the above is true for everyone else - and we’re already in a melting pot of individuals with different communication styles. People are getting frustrated, making other people even more frustrated. It’s a frustration chain reaction!

All of this led to me into a cycle of sending some snappy responses, feeling terrible after time would pass, setting up time to profusely apologize face to face, and wowing to never overreact to work stress sources again… Until the next encounter that is. It all culminated with me getting entirely too frustrated between 8:00 and 8:05 am last Thursday and taking a day just to decompress.

And that reminded of something I’ve learned years ago, and I something I would practice with rigour - until the background frustration level rose that is.

Early in my career I’ve been taught to cool down before sending that angry ping or an email – type it up, leave it in my drafts - come back to it an hour or two later.

In 9 out of 10 cases I end up deleting the message feeling relieved that an incoherent stream of hatred never saw the light of day. Most of the time when I’m angry I don’t really have a goal I’m trying to accomplish (other than inform all the parties involved of my feelings), and that’s not a great basis for professional communication.

In the remaining case, I would end up completely rewriting that email to remove the hostile tone and focus on the source of the issue instead. There are problems that are worth addressing with candor – but candor is too often conflated for the lack of tact.

And it’s hard to take a break at work - because there are often so many things to do, and so little time to do them. Which makes taking a minute to breather feel like a waste of time, when it’s one of the most productive things you can do in the long run.

So here I am, putting these thoughts into writing to remember to take a break before initiating aggressive communications – hopefully the more I think about this, the easier it gets to remember to pause, self-assess, and disconnect.

-

On mentorship

A couple of months ago I had a conversation with a fellow employee – let’s call him Balgruuf – who decided to quit the grind and become a career coach. Shortly after I’ve witnessed them interact with our mutual acquaintance – Farengar – who was in a difficult spot in their career. Balgruuf was enthusiastically instructing on what are the exact steps Farengar must take, and in what order. It generally felt like Balgruuf had this whole career thing figured out, and Farengar just stumbled along. Needless to say, Farengar quickly changed the topic.

I haven’t stopped thinking about mentorship since that day. In the 10 or so years of my career so far, I’ve had a number of mentors - both formal and informal. I also get the opportunity to mentor people around me – both sides of the relationship really fascinate me.

I’ve had some mentors who worked really well for me - and some who didn’t. I also had more different level of success with mentoring people myself. And one of the defining factors in a successful experience was this: people conflate mentorship with giving advice – two different, but oh-so-close feeling things. Let me elaborate on the difference with a tangentially related example.

Sometimes my wife comes home and shares frustrations that inevitably arise after a long day at work. There’s little to no room for my input, because she needs somebody to just listen, or maybe a rubber duck to talk at. And sometimes my better half wants to hear my thoughts on the subject. Needing to vent and asking for advice are two completely distinct scenarios in this case.

Just like in my home life, sometimes people come looking for an advice. But more often than not, they’re looking for mentorship.

Giving advice is prescriptive, while mentorship is more nuanced, and takes more finesse from both parties.

In Relationomics, Randy Ross discusses a role that relationships play in personal growth. He talks about the harmful “self help” culture which discounts the value of human element in self-development.

This is the gap where mentorship fits in. There’s one huge “but” though, and that’s the fact that the person needs to be ready for the specific feedback they might be getting.

Mentor is there to guide the internal conversation, encourage insight, and suggest a direction. Mentor is there to identify when someone who’s being mentored is heading in a completely wrong direction, or not addressing the elephant in the room.

In fact, I’ve been noticing a trend at Google to avoid trying to use the word “mentorship” overall, to avoid the go-to advice slinging attitude of your everyday Balgruuf. And it’s been a helpful trend - since framing mentorship relationship around guidance and reminding mentors to let those who are mentored to drive the growth is crucial for healthy peer to peer learning.

Even if so-called mentor has some aspect of life completely figured out for themselves, the person who’s mentored must drive the whole journey. Otherwise there’s really no room for growth in that relationship.

-

Adjusting to working from home

Like many, I moved to working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parts of California enacted shelter-in-place order back in March, and it’s been over a month and a half since then. I briefly worked from home back in 2013 as a freelancer - and I really got the whole work/life balance thing wrong. So this time around I’ve decided to approach remote work with a plan.

My day begins around 7 or 8 am, without too much deviation from schedule. I used to bike to work before the pandemic, and I try to head out for a 30 minute ride in a morning a few days a week. There aren’t a lot of people out early, and I love starting my day with some light cardio.

I share breakfast and coffee with my partner, often while catching up on our favorite morning TV show. At the moment I’m being educated on Avatar: The Last Airbender. Ugh, Azula!

Breakfast is followed by a calendar sync. We check if either of us have overlapping or sensitive meetings. That way we know which calls either of us needs to take in another room - and which are okay to have in our workspace. Both of our desks are in the living room, and we use noise cancelling headphones throughout the day to help with focus. During the day we convert our bedroom to an ad hoc conference room.

By 9 am, I have my desk set up: I replace my personal laptop with its corporate-issued counterpart. An external webcam helps with the image quality, and a dedicated display, keyboard (Vortex Pok3r with Matt3o Nerd DSA key cap set), and a mouse (Glorious Model O-) alleviate the cramped feeling I get when using a laptop.

Most importantly, I’m showered, groomed, and dressed by this time. While working in whatever I slept in has worked well for occasional remote Fridays, it proved to be unsustainable for prolonged remote work. Whenever I wasn’t dressed for work, I found myself slowly drifting towards the couch, and trading a laptop for my phone. In fact, some days I dress up even more than I used to when going to the office!

This is where the clear separation between home and work is established. I’m fully dressed and have my workstation set up: it’s work time!

I spend the next few hours busy with heads down work, usually working on a design, writing some code, or doing anything which requires concentration. Playing something like a Rainy Cafe in the background helps me stay in the zone.

Back in the office, 11 am used to be my workout time: a gym buddy of mine would consistency exercise at 11 am, and I adopted the habit of joining him over the past few years. I decided not to move the time slot: at 11 am I change into my workout clothes and exercise: 30 to 45 minutes of bodyweight exercises or online classes use up the remainder of my morning willpower. I’m so glad there are thousands of YouTube videos to keep me company!

My partner and I alternate cooking, and the next hour or so is reserved for cooking, lunch together, and cleanup. Remember the noise cancelling headphones? We haven’t heard (and often seen) each other since morning! Getting to share lunch daily has definitely been the highlight of staying at home for me.

After that - back to work: design reviews, meetings, busywork.

I wrap up around 5 pm, and make a point not to work past that. I swap out my work laptop for my own (even if I’m not planning to use it), and stow it away for the night. Disassembling my setup paired with showering and changing into house clothes creates a solid dividing line between work and home.

Cooking dinner together and evening activities follow, but that’s a story for another time. Stay healthy and productive!

-

Lessons learned: engineering productivity

I enjoy optimizing the way I work: the less time I can spend on something without sacrificing quality - the better. Below are few ideas on the subject of engineering productivity I’ve successfully applied in my career.

Don’t work long hours

A fascinating paper was released in 2011 by a group of Israeli researchers, who studied the factors which affect if prisoners were given a parole or not (source: Extraneous factors in judicial decisions.

First prisoner in a morning has approximately 65% chance of being released. With every next case, the chance dropped significantly, reaching nearly 0% starting with the third case. After returning from a lunch break, odds of a prisoner being released went back up to 65%. And once again, with each new prisoner the odds decline rapidly.

Authors of the paper suggest that making decisions depletes a limited mental facility. People start looking for shortcuts and making mistakes.

Working long hours is something we’ve all done more than once. Be it an upcoming deadline, fascinating problem, or a personal project. The problem with working too long is that you’re doing a poor job without realizing it.

I try to avoid working more than 7 hours a day, and there are people who get an incredible amount of work done under an even shorter amount of time.

This is probably explained by a phenomenon called “ego depletion”: the idea that self-control or willpower draw upon a pool of limited mental resources that can be used up. When the energy for mental activity is low, self-control is typically impaired, which is what is considered to be a state of ego depletion.

Dangers of burning out

Another problem with working too long - is a possibility of a burnout.

A while back I worked as a freelancer for a client of mine. I worked long hours from home office. This was my first time working from home for such a long period of time, and I made a number of mistakes in the beginning. One of which was working too much.

I’ve put in a number of 12-hour marathons in order to get more work done. I was on call most of the time. I became overwhelmed with all the work I had to get done. I started losing interest in work and feeling like things are getting out of my control. Every day felt like a bad day.

Those are the symptoms of a burnout. Feeling of life spinning out of control and feeling like nothing you do makes any impact.

I broke out of a mental prison of a burnout by getting a better work-life balance, enforcing exercise routine, and never working more than 8 hours a day. 7 in most cases.

Work-life balance

Another thing I learned from working from home is how to keep a work-life balance. Not having a separate office and living in a 1-bedroom apartment with my wife, I had to barricade myself in a far corner of a bedroom and turn it into a physically separated office space. That was the space I worked in, and it remained empty after I was done and until I started the next work day.

Work-life balance deserves a special say: it’s the difference between doing an amazing job and going insane. Set aside time and place for work, and never allow a bleed-through. Don’t be on call if you can avoid it. Don’t open or reply to work-related emails at your spare time. Office is for work and home is for family.

Distraction-free environment

Everybody is aware that interruptions hamper productivity, but not everyone actively avoids interruptions during work. Replying to a text message, quickly checking your social network notifications, or looking up that one thing you’ve been forgetting to look up for days - all of this impairs your mental ability to complete the task within a desired time frame and, more importantly, with high quality.

According to various studies it takes from 20 to 30 minutes to get regain the same level of concentration and productivity after a single act of disruption. A 2014 study from George Mason University found that students composed lower quality essays when interrupted only a few times throughout both planning and writing phases. Distracted students performed considerably worse, even though they were given additional time to complete an assignment in order to make up for the interruptions.

Know your tools

Use a single editor well

- Pragmatic Programmer, Tip #22.

This is lower level tip than the rest, but something I find utterly important in my daily work. We, the software engineers, spend at least half the time editing some sort of text - code, email, documentation. Taking time to improve the knowledge of the software you use every day pays off.

- Using Gmail? Learn the keyboard shortcuts.

- Use Eclispe? Do the same. Search for plugins which can make your everyday work faster and easier.

- Use command shell for daily work? Practice your shell scripting skills, find the tools that let you do more work with lesser amount of typing.

- Pick up touch typing. It’s also a part of your toolbox. Why think about keying words in? Lower error rate while typing - you need to go back less.

For instance, I do all my work in shell. I use Tmux for creating and navigating multiple sessions. I use Vim for all my editing needs - code, documentation, blogging, composing long emails (via Mutt). I touch type, so working in a text mode is easy.

Over the years I accumulated aliases for all the frequently used shell commands. All the Vim and Tmux shortcuts are a part of a muscle memory. Jumping from file to file or from one place to another within a file doesn’t take any mental effort and is accomplished with only a couple of keystrokes.

By eliminating the need to think about or spend too much time working with low level concepts - you free up the mental bandwidth for higher level reasoning and problem solving.

Read, don’t stop learning

As per DeMarco and Lister, authors of “Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams” - one book is more than most programmers read each year. This is the same point Steve McConnell’s “Code Complete” emphasizes.

A lot of programmers don’t read books. A few even don’t follow relevant blogs or websites. Don’t do what software engineers had to do in the olden days: coding by error in isolation from the rest of the industry. Read a book, learn something you don’t know about. A single book read from beginning to end contains wider array of information compared to disjointed articles some programmers limit themselves to.

As Jeff Atwood suggests in his article “Programmers Don’t Read Books - But You Should”, pick up one of the timeless books - not affected by changing technologies and processes.

-

Impact-driven development

It is my fifth year working as a professional software engineer, and I think it’s a good time for me to share a few tips, dos, and don’ts I learned throughout past four years. This is the first article in a series of three, and it focuses on development process.

Moving towards becoming a senior engineer, I noticed paying more attention to the impact my work produces. These days I would much rather compile a number of small simple changes to “wow” the users, as opposed to building unnecessarily complex nice-to-haves. This sounds simple and straight-forward, and some reader might even say “That’s silly, everybody knows that”. However significant number of engineers I meet don’t concentrate on how much impact they produce.

It’s easy to get caught up in a daily routine: you close an issue after issue, there’s a stable flow of requirements from the business meetings. It’s not always easy to know when to stop and think “Do I really need to do this?”.

Get the priorities right

Divide amount of impact task produces by amount of effort you’ll have to put into completing it. Arrange the tasks by this factor.

More often then not you can drop items with low impact/effort ratio.

Separate what is needed from what is asked

Know who the stakeholders are for each task, feature, or a project you work on. Understand their underlying motives. Anyone can fall a victim of an XY problem, it is your responsibility as an engineer to make sure that stakeholders ask for what they actually need.

Know when to say “No”

In the very beginning of my career I gladly took every single task thrown at me. It soon became an issue: work that actually needs to get done is not getting done quickly enough. Knowing when to say “No” is an art that takes practice.

Think about your work

Beware of routines, repeating the same workflow time after time is damaging when it comes to building software. Stop each time before you proceed to the next step, and ask yourself if you’re performing the task in the best way possible. Be mindful about your work.

Be a catalyst for change

Be the first to promote the change. Did you notice a poor practice on a project? Begin a more efficient practice (if it’s appropriate based on your role in a team of course). Don’t go on telling people how wrong what they use is. Show everyone how the new way is better on practice, and your colleagues will adopt successful trend.

Don’t fall a victim of deferring responsibility: be aware that when multiple people are involved, every member of a group relies on other people to get things done. Be the one to take on responsibility when it’s unclear who should.

-

Dark side of technical interviews

It upsets me greatly, since there is no immediate or obvious solution to an interviewing scheme which will fit every company. Some companies seem to find processes which work for their size and culture, while others struggle to do so. Human resources management is a complex subject, and it’s hard to get right.

I have experience with only a small subset of interviewing techniques, but none of the following interview components I employ seem satisfactory.

Screening

Screenings are usually done by recruiters, employees whose skills are in seeking and evaluating prospective assets to the company. The first problem here is that recruiters are not team members. Recruiters might do a really good job at, say, finding good recruiters - since this is their domain, and something they are inherently good at. But they don’t develop software. Recruiters don’t work with tech leads and team members, they don’t have the slightest real life idea what managers and leaders want from the potential hire. Hell, the problem is - most team leads don’t even know what kind of person they need. And if they do, they don’t have a slightest idea on how to communicate this properly to the recruiters.

In an ideal world, software engineers and team leads would do recruiting themselves. But this way they would not have time to do their own job, and would thus become recruiters. Boom, the company lost a good software engineer. So you end up hiring recruiters, who have not the slightest idea what a team needs (“person has to be proficient in Blah-blah-blah” is like saying that a writer has to be an expert at writing about red cubes).

Is there a solution? Probably, maybe, I don’t know. Maybe recruiters and software engineers have to communicate more. Set up meetings to discuss team needs, go through training in regards to identifying key traits in prospective engineers. Teams of engineers have to communicate their preferences better. Engineers are hired to fit the culture, not to be a “rock star”. Geniuses don’t go through the HR process, future team members do.

Interview with another engineer

This, even though it has a good intent, is a big whopping failure. What this originally is meant to do - is have a potential colleague evaluate the candidate. Sounds like a fantastic idea in theory, and sometimes it even works the way it is intended to.

Most of the time, however, you end up with a competition-driven technological fanatic bombarding an interviewee with smart-ass obscure trick questions they discovered that one time browsing their favorite language’s mailing lists from the year 1990. In the worst-case scenario, the candidate is not able to answer any of those terrible questions, satisfying the interviewer’s ego while she cranks out a negative report to a recruiter.

In a slightly better version, an engineer will give a candidate a set of hands-on tasks which rarely have anything to do with the real job responsibilities. One version of this: pair programming segment, on the engineer’s machine, under stress and with shaking hands. Are we hiring contestants for a hackathon?

When it comes to software engineering, everyone suddenly forgets that writing code is the smallest portion of the day. This might not be the case for junior programmers, but they are not the ones companies are wasting their hiring resources on. It’s the mid-level and senior workers who weren’t even evaluated on half of their job responsibilities. How are their human interaction skills? Are they pleasant to work with? Will they have issues with company policies? Will they fit? These questions are as important as one’s ability to put together a few lines of code.

Maybe interviewers have to spend less time checking how well candidates write code under pressure, and more time evaluating if they will be a good match for the company’s culture. How do they react when you point out their mistake? Can they communicate concepts clearly? Are they good at marketing themselves? You hire people, not code generating machines. Unless that’s what you need, of course.

Home assignments

Home assignments are something I personally like and despise and the same time. And I find it sad that there are a number of big fat minuses with this approach. First, one might find it insulting. “What, I have to write code for you in my own time? Couldn’t you evaluate me on an interview or something?” This method can turn a lot of people off, and unfortunately the ones that stay are not typically the best quality.

As my co-worker wisely pointed out, if you have a choice between two overall equal companies and one requires you to do more work before being considered - you will naturally pick one that accepts you easier. Any job seeker would feel more appreciated and trusted taking that route.

The honesty factor doesn’t play much role here, since you usually can tell if the person did not write everything herself during the one-on-one followup. But the cost does play a role. The interviewer has to come up with a relatively unique assignment, spend time reading and evaluating the written program, give feedback on a follow-up interview. This adds up if you have many candidates.

This technique does make sense when the list of candidates needs to be narrowed down, or when you’re at the top of your domain. Who wouldn’t complete a day-long homework for Google? Many people will happily spend a sleepless night for an employment opportunity. Even more wouldn’t, especially if someone has a number of options lined up in front of them.

What about other methods?

There is a large number of various interviewing techniques out there. Some companies combine the above specified methods to have a bare-bone hiring template. Some make candidates do paid work for a few weeks before being accepted as a new hire. Some don’t bother and just decide to wing it.

This is still a developing area; I am afraid the solution has to be obtained through the method of trial and error. There seems to be no success recipe which works for everyone. There are, however, a number of alternative solutions. I don’t think most companies put enough resources in finding a successful technique, instead opting for whatever method is in season at the moment.