-

PC Gamer physical edition is good, actually

I spend a lot of time in front of a computer or a phone, even now that I have a kid. Hey - she needs to sleep, and I have some time to kill. Many of my hobbies revolve around a screen too - like playing video games, tinkering with stuff, or writing.

It’s unsurprising that I’ve been wanting to take a step away from the screen and find a way to engage with physical media more. I used to read a lot of books - I don’t anymore. I listen to audiobooks sometimes, but it’s been a good year or two since I last sat down and read a book cover to cover. That’s fine - life ebbs and flows, and even though sitting down and reading books used to be a huge part of my life - they aren’t today, and that’s okay.

But it’s nice to put down devices and just hold something in your hand.

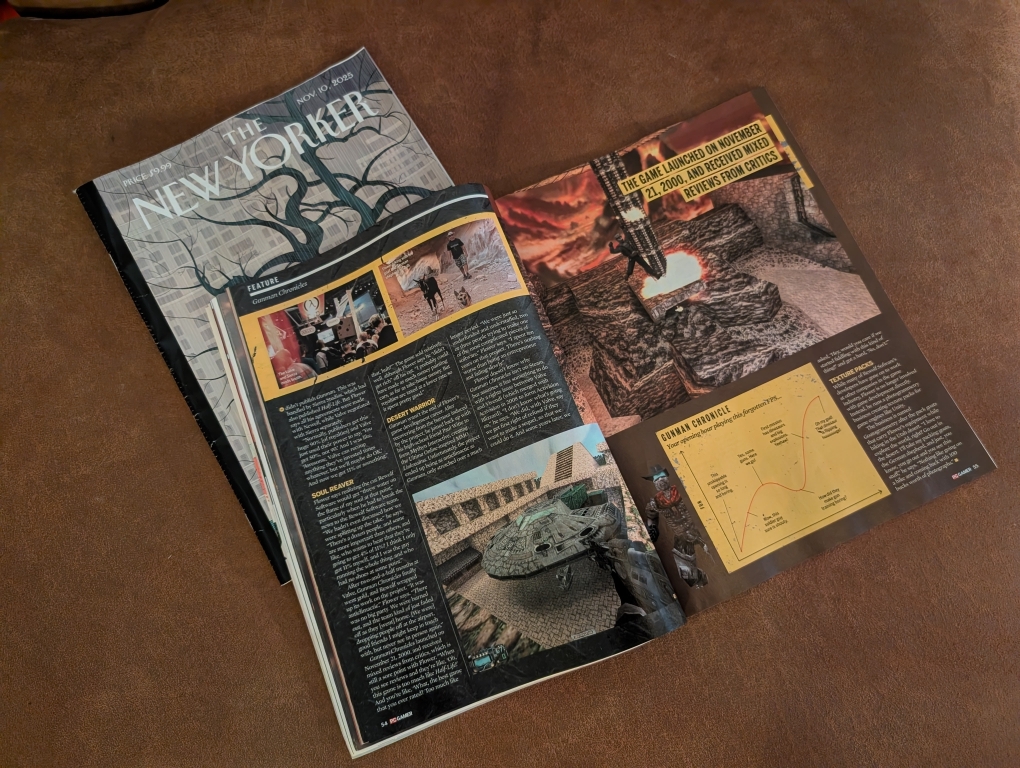

I worked around this limitation though and decided to get more into magazines. Yeah, print media is still alive and kicking. We have two physical publication in our household this year - The New Yorker, and PC Gamer. Two very different magazines, and you can probably tell which subscription appealed to my wife - and which one to me.

I’ve been reading both, although I’ll admit that PC Gamer has received more of my attention. Hey - unlike The New Yorker, which oppressively sends you a new issue each week, PC Gamer has been sending me issues monthly. And I don’t need to tell you that The New Yorker is a great publication - it’s got hell of a reputation, and for a good reason. It’s quality journalism, and peak writing, or so I’m told, but it certainly reads that way despite my limited knowledge on the subject.

But I do know a thing or two about video games, and one thing I know is that gaming journalism from major publications - PC Gamer included has been steadily declining in quality over the past decade. Between corporate relationships, out of touch and burnt out reviewers, and sanitized, often generic pieces - I have been avoiding mainstream gaming media. There are lots of small independent reviewers who do a wonderful job covering the titles I care about, and I trust those a lot more.

I’ve read somewhere that the print edition of PC Gamer is somewhat different. You still have the same people working on the issue, but the time pressure’s different, articles can’t be updated once they go live, and there’s much more fun and creative writing. I’m sure all of that’s available offline too, but I don’t think I would’ve read any of that if the magazine wasn’t already in my hands.

Reading editions of PC Gamer feels like stepping a time capsule, in big part due to fairly substantial retro game coverage - you can’t exactly publish breaking news in a monthly print, so the focus is much more on having interesting things to say. Chronicles of Oblivion in-character playthroughs, developer interviews, quirky reviews - there’s lots to love.

I’ve heard Edge Magazine is well known for high quality writing and timeless game critique. I think I’ll check that out too - here, I just subscribed.

-

AI-assisted overconfidence

Like many of my contemporaries, I’ve been experimenting with AI, and one of the bigger challenges I’ve run into isn’t around output quality, hallucinations, or other issues. No, the biggest issue for me has been the overconfidence AI tends to instill in the user.

Now that I think of it, South Park had an episode on the topic, called “Sickofancy”. In it, an AI assistant was overly encouraging to Randy’s obviously terrible ideas. Another source, winther’s essay on the pitfalls of AI-assisted writing briefly touched the topic, too.

More than once I tried to use AI for brainstorming, and AI convinced me of terrible ideas instead of offering a human’s healthy scepticism. I tried using various models for help with writing, and each time AI convinced me the output is wonderful, and each time I showed the output to my wife she said something to the tune of “This doesn’t sound like you at all, it reads more like a timeshare advertisement”. And she’s right every single time, because I’ve really struggled with getting meaningful critique from today’s chat bots.

This is an unsurprising finding, but I think it’s worth noting. Working with AI tooling today is like having a writing partner who’s read every book out there, but never experienced a single emotion in life and doesn’t know how to contextualize the ideas. I wonder why’s that?

Even when prompting the models to not be overly agreeable or requesting pushback - the models lack judgement. You ask them to evaluate your idea - they’ll spit out that it’s the best idea ever conceived. You ask for criticism, you’ll get told that it’s a terrible idea. Even rubber ducking - using an inanimate object as a sounding board that is - yields better results in my experience, since at least I get to utilize critical thinking.

This isn’t really an anti-AI rant or anything. The technology is here, you can’t put it back in the box, and there are real use cases out there (hey, I just saved myself a few minutes of fiddling with a spreadsheet formula by getting Gemini to do it) - but human overconfidence supported by AI is a real problem we’ll have to be mindful about.

-

The Yamaha moment

There’s this old joke:

- Me: I’d like to buy a piano.

- Yamaha: We got you!

- Me: I’m also looking for a motorcycle, where could I get one?

- Yamaha: You’re not gonna believe this…

I just had my own Yamaha moment. I was looking for a good pepper grinder, and I just found that one of the best pepper grinders on the market is made by… Peugeot. Yup, apparently the car company produced great pepper grinders, bicycles, and cars, in that order.

Live and learn.

And yeah, the pepper mill is sturdy, feels and looks great, and the grinding mechanism comes with a lifetime warranty.

-

Ego and the moving finish line

This is an entry to the IndieWeb carnival on ego hosted by bix.

In case you don’t know me - I’m Ruslan. A father, a husband, and a big nerd for video games and optimization problems. A few years ago, I would’ve started this intro differently: “Hi, I’m Ruslan and I’m an engineering manager at Google.” Oh - I’m still a manager at Google, but my priorities in life are different, and the shift is driven by the way my relationship with ego has changed over the years.

Over a decade ago, in my early twenties, I seeked recognition. I wanted to be widely known and respected. I moved to the United States from another country, pursued a career in tech - hopping between companies until landing at Google. This was huge for me, as I admired the company growing up, and working at Google felt like a peak achievement for a little computer nerd like me.

But I haven’t really savored the accomplishment. Now that I got to Google, it was all about getting to the next level, getting a promotion, bumping up my salary, expanding my span of influence, and so on. I compared myself to other early-twenty-somethings. Look, Mark Zuckerberg started Facebook at age 19, and I’m already a few years behind! Did I want to start a company? No. Did I even like Facebook? No, I didn’t. But that didn’t stop me from comparing myself to others, and it leached the joy out of life.

The generational curse of productivity certainly has something to do with it - I couldn’t just relax and savor the victories. I had to work hard for the next milestone. But a huge driver behind my early professional achievements was my ego. I wanted to be the best, and I wanted others around me to know it. I simply didn’t know a different way to live.

Throughout my early years I was really concerned with what people thought about me. I still struggle with it. And professional success felt like a way to bring authority into the conversation - “look, you can’t think poorly of me, I’m mister big pants in a serious company”. Mind you, we’re talking about an imaginary conversation in my own head.

In my mid-twenties I met my now-wife, who had a much more balanced outlook on life. She’s a hard worker too, but her achievements weren’t driven solely by the need to be seen by others as something else. No, she simply did things she was good at, and did them well. There’s lots of professional pride, yes, but it just felt… healthier? We both were ambitious, we both wanted to do our work exceptionally well, but while I wanted to be seen as the best, she just cared about her craft - regardless of who’s watching.

That was a major change from how I approached life, and her attitude rubbed off on me. I tried to decouple my own self-image from my professional successes. I began to engage in hobbies for the sake of enjoyment.

Look, I started this blog back in 2012 to bolster my professional image. I wanted to appear attractive to prospective employers, and I wanted people to see how many important thoughts I have, and how many cool things I know. This blog is very different now, because I have less people I care to impress. I don’t want a large audience.

Do I get excited when an article I write goes viral or I get a royalty check from my book in the mail? Absolutely. But do I get worked up when only a single reader gets through the entirety of what I write? Not anymore, no, because my ego as a writer needs less feeding than it used to. That’s why I removed comments and other visible indicators of popularity on this blog (eh, and I just don’t want to be tempted by the pursuit of bolstering my own ego).

In my mid-30s, I care less about impressing people. It helps me be a better listener, a better friend, or even just a better fleeting acquaintance. I have richer interactions with others when I don’t try to impress them. It ain’t perfect, and I find myself struggling - but I feel like I’m on the right track. I know I’ll win when I won’t be checking the view counts on this piece though.

If you’re curious about what other writers have to say about ego, I recommend you check out other entries on IndieWeb Carnival: On Ego.

-

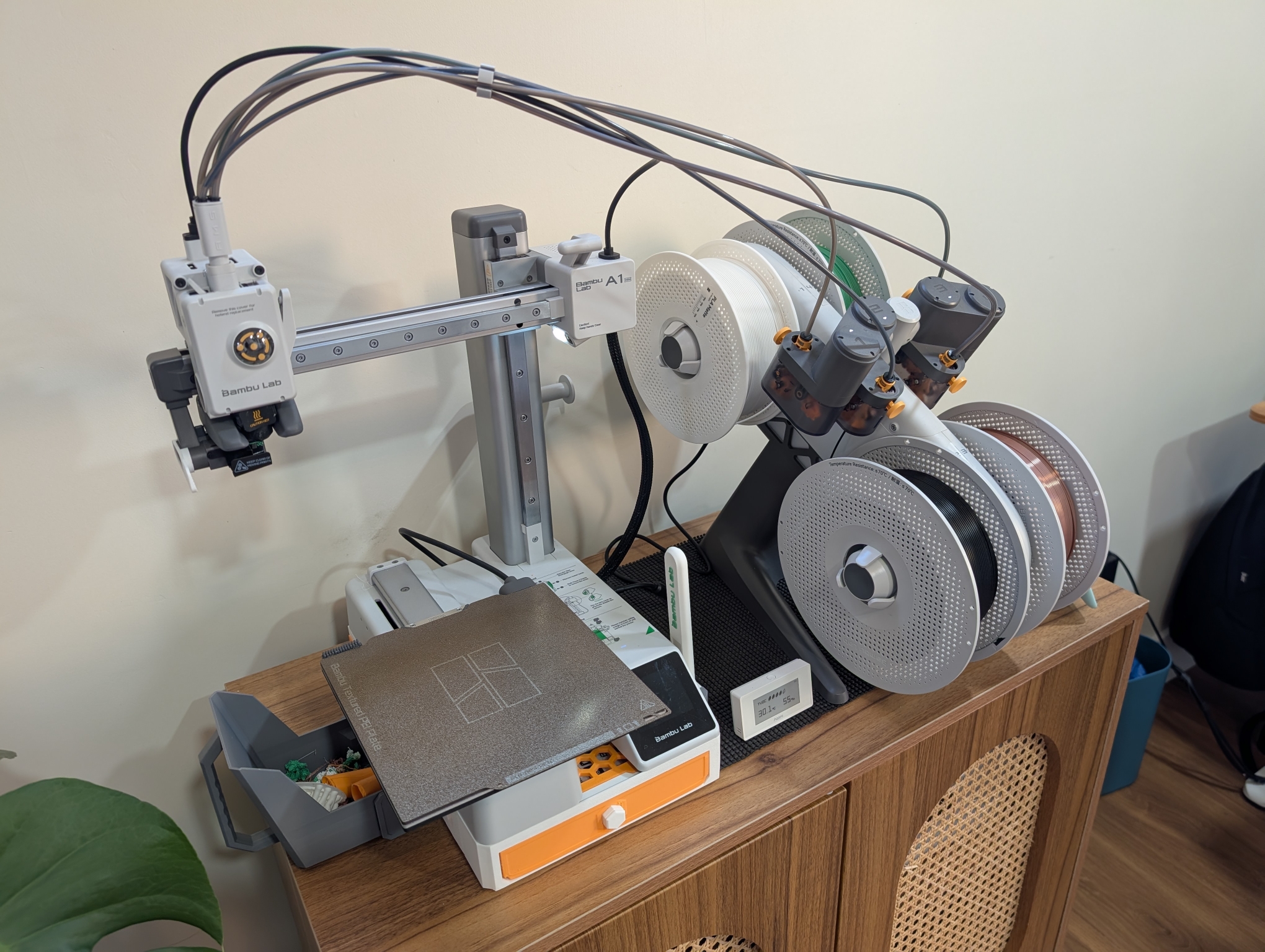

Thoughts on 3D printing

A few months back my wife gifted me a 3D printer: an entry level Bambu Lab A1 Mini. It’s a really cool little machine - it’s easy to set up, and it integrates with Maker World - a vast repository of free 3D models.

Now that I’ve lived with a 3D printer for nearly half a year, I’d like to share what I’ve learned.

It’s not a free stuff machine

After booting up the printer, printing benchy - a little boat which tests printer calibration settings, and seeing thousands of incredible designs on Bambu Lab’s Maker World - I thought I will never have to buy anything ever again.

I was wrong.

While some stuff printer on a 3D printer is fantastic, it’s not always the best replacement for mass produced objects. Many of the mass produced plastic items are using injection molding - liquid plastic that gets poured into a mold - and that produces a much stronger final product.

That might be different if you’re printing with tougher plastics like ABS, but you also wouldn’t be using beginner-friendly machines like the A1 Mini to do that.

So yeah, you still need to buy the heavy duty plastic stuff.

And even as you print things, I wouldn’t say it’s cheaper than buying things from a store. It’s probably about the same, given the occasional failed prints, costs of the 3D printer, the need for multiple filaments, and the fact that by having a 3D printer you’re more likely to print things you don’t exactly need.

It makes great decor and toys

Oh, I’ve printed so many useless things - it’s amazing. The Elden Ring warrior jar Alexander planter. Solair of Astora figurine. A beautiful glitch art sculpture.

I even got a 0.2mm nozzle (smaller than the default 0.4mm) and managed to 3D print passable wargame and D&D miniatures. Which was pretty awesome, although you have to pay for the nicest looking models, which does take away from enjoyment of making plastic miniatures appear in your house “out of nowhere”. I’m not against artists getting paid, they certainly deserve it, but printed models were comparable to an mid-range Reaper miniature if you know what I mean, which certainly isn’t terrible, but it’s harder to justify breaking even. Maybe I could get better at getting the small details printed nicely.

Oh, and if you’re into wargames - this thing easily prints incredible terrain. A basic 3D printer will pay for itself once you furnish a single battlefield.

You still need to fiddle with settings

Once you’re done with printing basic things, you do need to start fiddling with the settings. Defaults only take you so far, and if you want a smoother surface, smaller details, or improvement in any other quality indicator - you have to tinker with the settings and produce test prints.

It’s a hobby in it’s own, and it’s fun and rewarding, but this can get in the way when you’re just trying to print something really cool.

It shines when you need something very specific

But the most incredible feeling of accomplishment came when I needed something specific around the house, and I’d be able to design it.

We bought some hanging plants, and I wished I could just hang it on the picture rail of our century home. And I was able to design a hanger, and it took me 3 iterations to create an item that fits my house perfectly and that I love.

My mom needed a plastic replacement part for a long discontinued juicer. I was able to design the thing (don’t worry, I covered PLA in food-safe epoxy), and the juicer will see another few decades of use.

Door stops, highly specific tools, garden shenanighans - the possibilities are endless. It took me a few months to move past using others’ designs and making my own - Tinkercad has been sufficient for my use cases so far, although I’m sure I’ll outgrow it as my projects get more complicated.

A tinkerer’s tool

3D printers aren’t quite yet the consumer product, but my A1 Mini shoed me that this future is getting closer. Some day, we might all have a tiny 3D printer in our home (or have a cheap corner 3D printing shop?), to quickly and effortlessly create many household objects.

Until then, 3D printers remain a tinkerer’s tool, but a really fun one at that, and modern printers are reducing the barrier to entry, making it much easier to get into the hobby.