Category: Finance

-

Our monthly family finance huddle

The title could be a bit misleading: I’ll be talking about how the Osipov household runs our monthly financial check-in. I’m not brave enough to share the details of our family finance on the Internet (but I’m happy to grab a coffee and chat - face-to-face I’m an open book). Because of that, this post is light on detailed screenshots and tables, opting in for generic visuals and overall vibes.

While my wife and I share the same values of frugality, not keeping up with the Joneses, and spending our money where it matters, our approach to personal finance differs. My partner thinks of money in terms of buckets - cash coming in from source X is different than cash coming in from source Y, and must be accounted for differently. It’s all about budgeting, a complicated web of accounts and buckets, as well as many automated transfers. I, on the other hand, have a much more free-for-all approach to personal finance. I don’t spend money if I don’t have to, and to me credit card points are no different than the dollars coming in from a paycheck. We’re both equally frugal, but we get there differently.

On the first of every month (plus minus a day or two - life tends to get in the way), my wife and I go through our financial check-in. It’s something we’ve done consistently for years, and I think in addition to controlling our spending, our monthly reviews have helped us be on the same page.

Since 2017 we’ve been keeping our finances in a spreadsheet. Originally built off of the IndyPendent’s one sheet to rule them all, it’s been rewritten many times over. It’s also a great opportunity to refresh the sheet during our check-ins. In fact, I’ve written about how we track portfolio allocation before - that’s one of the sheets within our larger file.

So, what does this monthly ritual involve?

First and foremost, we log the value of all of our accounts as of that day - 401k, investments, credits cards, mortgage - all of it. Having a log going back multiple years really helps. You get to see how your net worth and savings rates correspond with life and world events over time. Because of this rigorous accounting, I’m able to run fun analyses like savings rate plotted over 8 years.

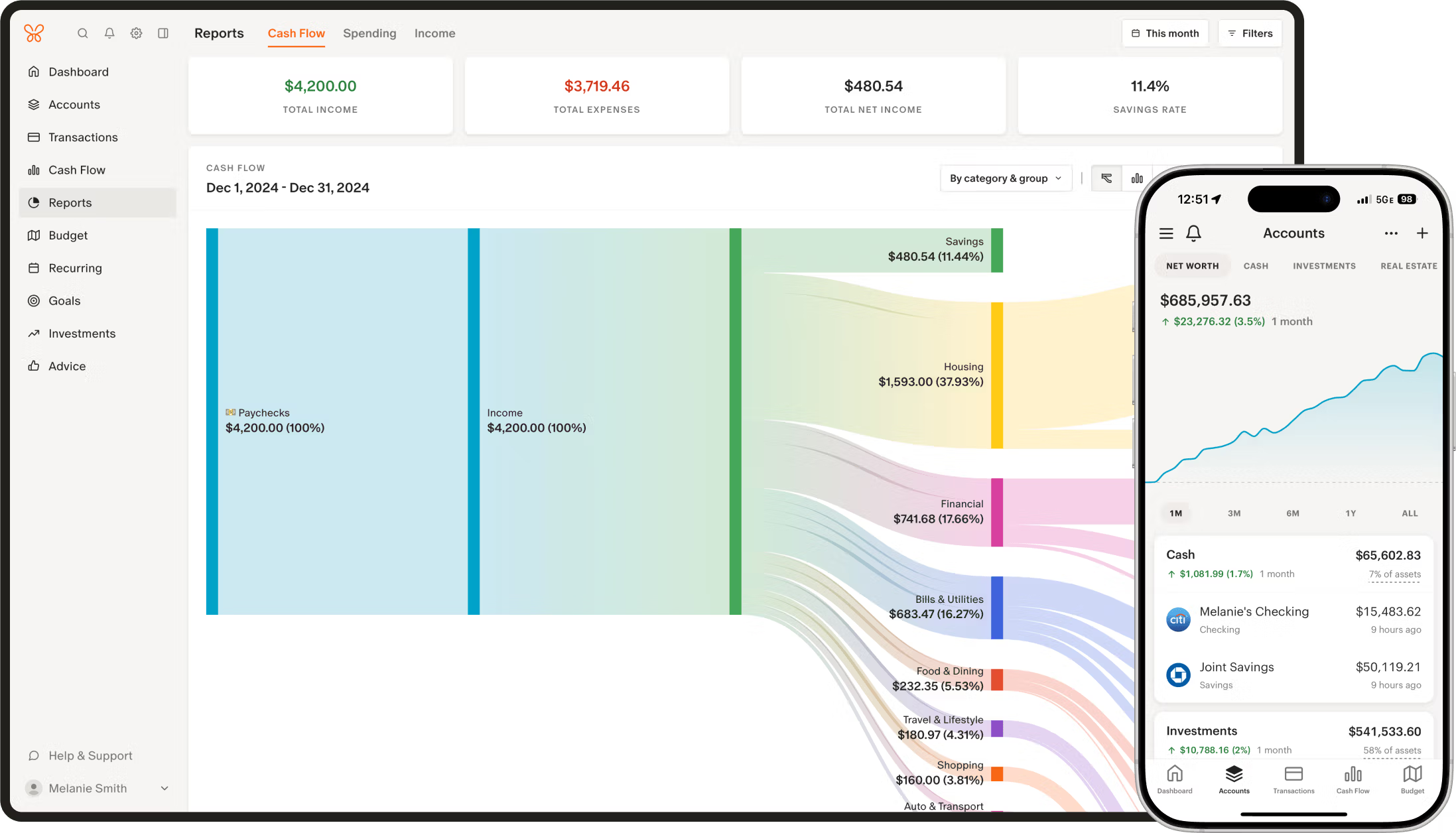

While we keep the original spreadsheet the source of truth, we sometimes try out different personal finance services. We always use the spreadsheet, but sometimes we might use something else alongside it. Monarch is my current favorite: it connects to our institutions, allows you to set rules for transaction categorization, and most importantly natively supports CSV imports and exports for every page. Monarch is worth the money (at least for now), here’s a 50% off the first year.

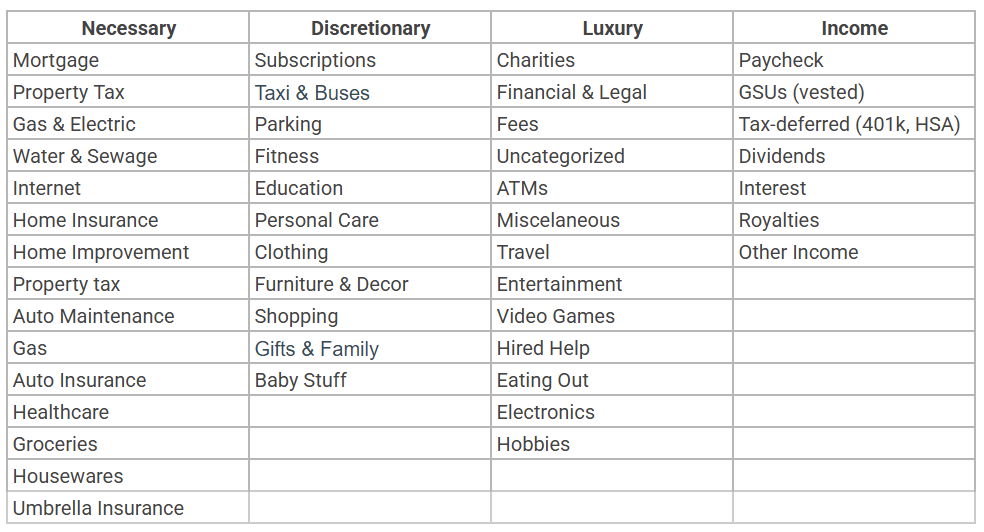

So, back to the first of every month. We use the same transaction categories in our spreadsheets and in Monarch, so we’re able to import the transactions one-to-one. And it’s great to be able to leverage robust Monarch categorization rules! This is where we track where every dollar goes.

Right, so updating spreadsheets and syncing Monarch is just the mechanics. The real meat of our monthly check-in is the conversation that follows. You might imagine that with my wife’s structured bucket system and my more, let’s say, holistic view (although my approach can be better described as “vibes”), these chats could get tense. But honestly, because we do this regularly, it’s usually pretty smooth sailing – more of a collaborative tune-up than a debate.

Here’s a taste of what actually goes down:

- Expenses recap: We eyeball the spending categories. “Okay, looks like dining out crept up a bit last month – maybe we dial that back?” or “Nice, we really kept the grocery bill down.” Sometimes it’s just acknowledging reality, like the inevitable sigh when we see the combined total for Amazon or Trader Joe’s. Seeing the numbers laid out often sparks easy agreements on minor adjustments.

- Looking ahead: This is crucial. “Hey, tax season’s coming up, do we have enough saved up?” or “We talked about that weekend getaway, should we start putting money aside specifically for it?” It prevents big expenses from sneaking up on us and lets us plan. My wife might earmark funds in our budget; I might just mentally note, “Okay, less random spending for a bit.”

- The big picture: How are we tracking towards the big stuff? Retirement contributions, mortgage paydown, saving for [insert next big goal here]? Even if the market’s doing crazy things (cue the “oh God where are the stock markets” comment), we look at our savings rate and long-term progress. It grounds the month-to-month fluctuations.

- Mixed methods: This is where our different approaches intersect. My wife might point out, “The ‘home maintenance’ bucket is looking low, and we know the fence needs fixing.” I might counter with, “Yeah, but overall savings look strong this month, maybe we can cash flow it?” Often, the solution is a blend – maybe we allocate a bit more to that bucket and agree to watch discretionary spending elsewhere. The shared goal (fixing the fence without derailing savings) matters more than how the money is mentally accounted for.

- Actions: The chat isn’t just talk. It often ends with concrete next steps. “Okay, I’ll transfer $X from checking to the investment account,” or “Let’s agree to cap ‘hobby spending’ at $Y next month,” or “You research refinancing options, I’ll look into estimates for that car repair.”

It’s not always a deep, soul-searching conversation with printed out visuals and a presentation to boot (that’s what a year-end review is for, anyway). Sometimes it’s quick: update the numbers, glance at the summaries, confirm things look okay, high-five, done. But having that dedicated time every month means we’re consistently aligned. It prevents financial decisions from becoming unilateral or sources of friction, instead turning them into regular, shared checkpoints, even with our different money brains.

Typically this would be the part where I share the spreadsheet template with you (or even pretty screenshots), but the spreadsheet is currently way too customized for our individual needs, and untangling it for more general use would be quite an undertaking. But let me know if there are any aspects that interest you and I can pull out the logic similar to what I did with our portfolio allocation tracker.

-

Three reasons to avoid market speculation

Hi, you’re likely a casual retail investor, and I probably sent you this link as we were chatting about investing. The topic comes up often, and I think I summarized my points rather well in this article.

I’m a vocal opponent of retail investors trying to time the market and invest in individual stocks. Here are three key reasons why I think you shouldn’t:

1. You don’t have access to the right information.

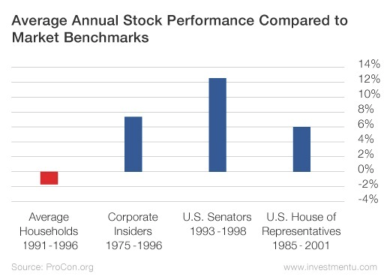

Unless you have insider knowledge (hello, esteemed congressmen), you’re not going to have information that institutional investors don’t already have. You don’t have the time, resources, expertise, and, more importantly, connections that financial institutions do.

Further, you probably have access to the wrong information - taking the news cycle and noise like public discourse into consideration.

2. You’re betting on growth.

Stocks are inherently speculative assets. You purchase a share in a company with the hope that the company will become more valuable than it is today. Even if the business is profitable, you’re making a bet that it’ll be even more profitable than it is today. Infinite expansion isn’t guaranteed, and a business can be profitable without growth.

Here’s Verizon, a telecom giant which, in a typical year, rakes in 80 billion USD in gross profit, but whose stock has been stagnant since the 2000s.

3. You’re speculating on top of speculation.

You’re not the only one trading on the stock market. And expectations of future growth are already baked into the share price: if you think Google stock is going to rapidly grow and expand, you’re more willing to pay more for the stock than Google is currently worth. By investing in a publicly traded company as a retail investor, you’re making a bet that it’ll grow more than what other (likely institutional) investors believe it will grow.

In a 2012 experiment, a cat outperformed three teams of institutional investors. The adorable findings are consistent with studies which indicate that investors routinely underperform compared to market indices.

Invest in low-cost index funds. If you don’t know much about the world of investing, consider opening an account with a respectable brokerage firm like Vanguard and invest in an appropriate target retirement date fund. That sounds boring but will reduce risk while exposing you to overall stock market growth. You can (and probably should, eventually) rebalance your portfolio as you learn more about market performance, your financial priorities, and your own risk tolerance.

Thanks for dedicating the time to read through this.

-

Seven years of Mastering Vim

Oh, how the time flies. I published the first edition of Mastering Vim in 2018. Since then, it has been translated to Japanese and received its second edition.

In 2021, I wrote about how much money publishing Mastering Vim has earned, and I think now’s the perfect time to get an update.

Mastering Vim was never meant to become a bestseller, but it did fairly well given the fact that I haven’t done much promotional work and haven’t been particularly active in Vim space since then.

For the first edition of the book, I receive 16% royalties. For the second edition, I negotiated a step-up based on publisher’s net receipts (over the lifetime of the book): it starts as low as 16% and climbs as high as 25% once the publisher nets £40,000 from my book.

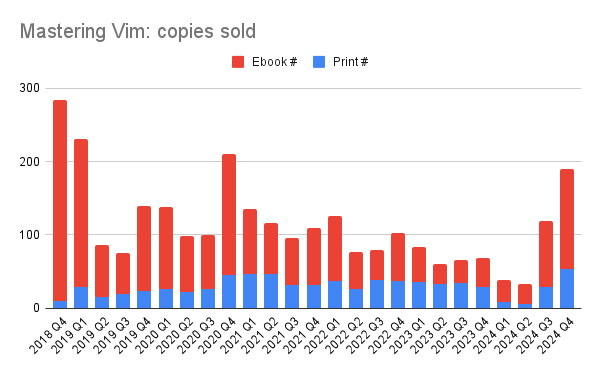

Here’s year over year sales and revenue data, you can see it to be predictable and steady:

Year Copies Revenue 2018 284* $363* 2019 533 $1,433 2020 548 $1,533 2021 458 $1,752 2022 386 $1,403 2023 279 $1,112 2024 381 $1,206 * Mastering Vim was published in Q4 2018.

On average, I earn about $5 for every print book sold, and a bit over $2 for every ebook sold.

In addition to book sales, I also receive a portion of translation fees (for the Japanese translation), as well as subscriptions to the publisher’s service (something I do not promote nor care about).

Book sales Translation fees Subscriptions $8,803 $1,669 $572 In the past seven years, Mastering Vim has sold close to 3,000 copies (not including the Japanese edition, which I have no visibility into). This has grossed slightly over $11,000 in total revenue. While this amount is definitely not enough to live off the royalty income, I have truly enjoyed learning more about the domain and becoming a subject matter expert throughout the writing process. Having a published book feels like a legacy artifact that I can be proud of. Of course, the quarterly royalty statements are a nice bonus as well.

If you’d like to see the book for yourself, Mastering Vim can be picked up on Amazon.

-

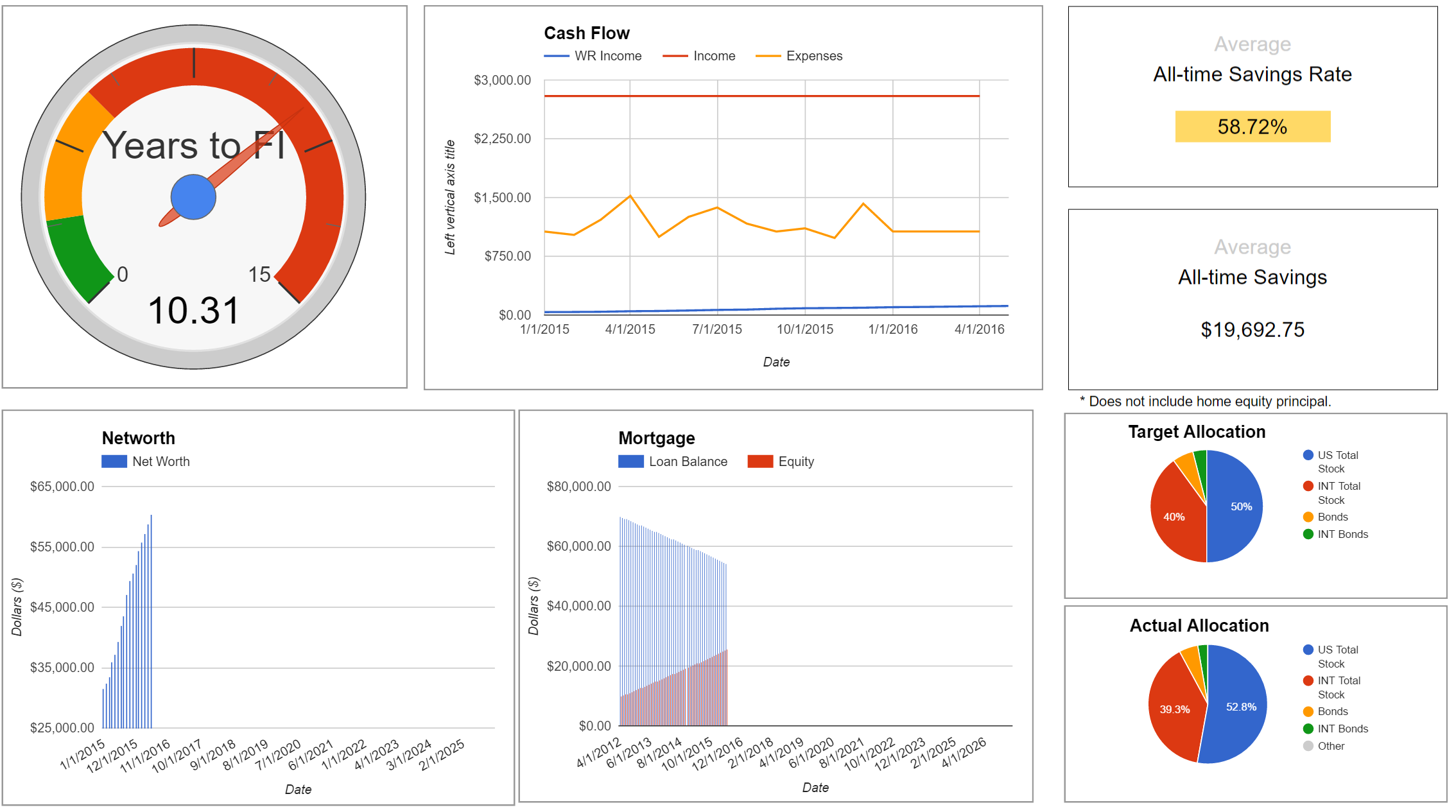

Tracking portfolio allocation

Financial independence is one of the core values in the Osipov household. We invest for the long term and maintain a stock-to-bond ratio that reflects our goals and risk tolerance. However, over time, the ratio gets out of date, and we use a handy spreadsheet to catch the imbalance and inform our adjustments.

It’s no secret that I love tinkering with spreadsheets: we keep a master spreadsheet which tracks our networth, income, expenses, mortgage, allocation, and any other little thing our heart desires. We perform a major annual financial review around New Year’s Eve, complete with presentations and champagne - it’s quite an event, and yes, we’re dorks. It’d be much harder to extract insights without diligent record-keeping throughout the year.

Each year we make a new copy of the spreadsheet, and we’re on 9th iteration at this point. Initially our spreadsheet was based on IndyPendent’s One Sheet to Rule Them All, but we’ve diverged quite a long time ago.

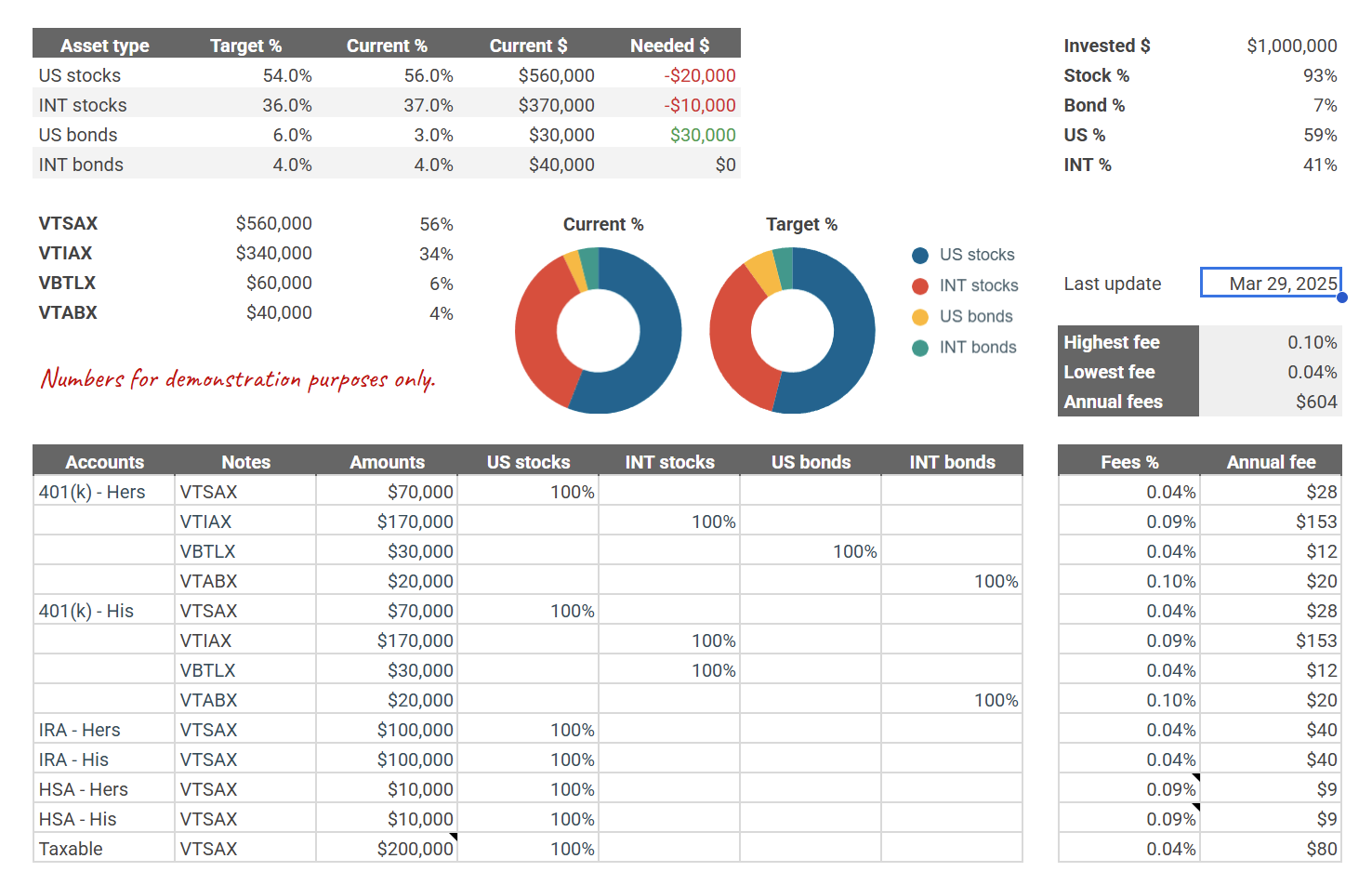

Here’s a screenshot of the sheet we use for tracking allocation within our portfolio and as a guide for occasional rebalancing (with some sample data filled in):

It allows me to set targets and see our current distributions: we care about stocks vs bonds split as well as US vs international market. It’s simple, manual, but has been working well for us. Over the years I tried more complex and “smart” solutions, but nothing beats this spreadsheet. Just like with our investment philosophy, simple truly is better than complex (thanks, PEP 20).

I extracted the allocation sheet from our mega-spreadsheet: feel free to copy Ruslan’s Allocation Sheet and tinker with it to your liking.

-

Experience with financial planners

As I’m starting to write more about early retirement, I think more and more about financial planners and advisors I’ve talked to along the way. The first financial planner I ever talked to (who’s been now fired from a role of my financial advisor and promoted into a position of friendship) reminded me about the beginning of the journey after reading one of the FIRE articles I’ve posted earlier this month.

I’ve talked to half a dozen financial planners over the past 5-or-so years. Some of those conversations have been very influential, and some have been more aggravating than anything else – but it was a net positive experience for me.

The aforementioned financial advisor I’ve had the pleasure to talk to was a colleague’s spouse. I’ve voiced my interest in early retirement, and we decided to sit down and run through a financial overview.

I’ve learned a lot from this meeting, and the advisor helped me frame my knowledge, and fill in the gaps for everything I’ve learned on the Internets. The biggest value came from leveraging tax-advantaged accounts and employment benefits: maximizing 401(k), IRA, and HSA contributions, leveraging IRA backdoor and 401(k) megabackdoor (I just talked about these in detail in “Accessing retirement funds early”). We discussed fund selections, risk profiles, and even touched on housing. It was great to have an opportunity to have someone who knows what they’re talking about answer all the questions that built up over the years.

The conversation had profound impact on my initial portfolio and investment strategy, and set pace for early retirement planning. With the confidence of having my plan and assumptions validated, I went on with my investments (employing the “slow, boring and steady” strategy, if you’re interested).

After some time said colleague and his spouse became our family friends: and I don’t much care for doing business with friends.

After that experience, I struggled to find the person I would work with for a prolonged amount of time.

At some point I thought I found “my guy”: a financial planner who was familiar with early retirement, and was eager to do additional research for just about any topic I could ask. Unfortunately for me it didn’t take long for “my guy” to soar through corporate ranks and get promoted past working with individual clients.

This is where the cracks started to show. For many financial planners, early retirement refers to age 55. And that makes sense – retirement in your 30s is such a niche topic! Most financial planning tools don’t account for this. Things like tapping into 401(k) or IRA balances before age 59 1/2 is not something supported by the rigid financial projection tooling.

Your typical financial planner will not be intimately familiar with the intricacies of early retirement – or any other niche topics for that matter. And that’s okay. Because financial professionals still know their shit – and it’s much easier for them to make professional judgement about things your smart ass found online.

The best financial planners I talked to were willing to listen and put in work outside of our calls. Those folks would understand my concerns, supplement their answers with research, and come back with educated opinions.

A model that works for me is providing my questions and concerns in advance of the call, giving the advisor time to research niche and domain specific questions.

Financial planners worked for me especially well for two purposes:

- Confirm that my understanding of something is correct.

- Tell me about things I don’t know or haven’t thought about.

This is where a financial planner pointed out that I misunderstood 401(k) contribution limits, or didn’t consider implications of varied cost of health insurance in retirement. This is the person I bombarded with an hour worth of questions about my auto insurance or the need for umbrella policy.

One time fee advisors worked best for me. I know some folks who moved assets under management for a certain percentage of those assets in fees, and are now trying to get out. This worked okay for them early on, but ended up not being what they want as they became more financially savvy. And it turned out to be oh-so-expensive in the long run.

And there are many things I had to watch out for along the road. Some advisors I’ve talked to seem to have no idea what they’re talking about, and just sound misguided. And it’s not solely my opinion - sometimes I would write down something a person would say, ask for independent opinion, and get back “What drugs are they on? I would like some of that!”

There’s also the question of their interest.

Some financial advisors might be inclined to sell things like lucrative whole term life insurance, and while in certain cases it’s appropriate, it might not always work for all individuals. But it sure as hell pays well for those advisors, so it’s hard to fault them for peddling the insurance.

The United States has a fiduciary system that’s supposedly requires a planner to work in your best interest (I personally learned about it from this Last Week Tonight show episode).

If you’ve done a lot of your own research (and especially if you haven’t) – it certainly wouldn’t hurt to talk to professional and review your decisions. Someone who has an idea of what they’re doing can go a long way in making sure you’re not heading down the wrong path – and if you are – you’re doing it with full awareness of the trade offs you’re making. Just be mindful of pitfalls when doing so.

-

Accessing retirement funds early

As I’m reentering a society after the pandemic, I had the pleasure to chat with a family friend about early retirement strategies. One of the many topics that popped up was about accessing age-locked retirement funds - namely 401(k)s and IRAs. Conventional wisdom is that these account stay locked until you hit a certain age, but funds from these accounts are accessible as long as you’re ready to jump through some hoops.

I put together this post to test my understanding of the subject, so please let me know if there’s something I misunderstand. I used the IRS and the United States Code websites as the sources of truth, and I link to each throughout this piece. The links are likely to get out of date within a few months to a year though, so don’t hold your breath for those.

This article is for retirement accounts in the United States only.

Tax-advantaged accounts

There are 5 tax-advantaged retirement vessels that I’m somewhat familiar with:

- Traditional 401(k)

- Roth 401(k)

- Traditional IRA

- Roth IRA

- HSA

These are not the only tax-advantaged accounts out there for different employment situations, but I think these are fairly common. Here’s a quick reference for each with some stats as of June 2021:

401(k) Roth 401(k) IRA Roth IRA HSA Employer-sponsored? Yes Yes No No Sometimes Allows for employer match? Yes Yes No No Yes Tax-advantaged contrib. limit $19,500 + match $19,500 + match $6,000 $6,000 $3,600 Total contrib. limit $58,000 $58,000 $6,000 $6,000 $3,600 Contrib. increase at age 50+ $6,500 $6,500 $1,000 $1,000 $1,000 (55+) Taxation Deferred Exempt Deferred Exempt Exempt/free Withdrawal timeline 59 1/2 59 1/2 59 1/2 59 1/2 or 5 years Qualified/65 Mandatory withdrawal 70 70 72 N/A N/A Early withdrawal penalty 10% 10% 10% 10% 20% I dig into each a little bit more below.

Traditional and Roth 401(k)

401(k) is an employer sponsored plan: it allows you to invest in a choice of funds selected by your employer. 401(k) often comes with an employer match, which allows the employer to contribute additional amount on top of the tax-advantaged contribution limit. At age 50, you can contribute additional amount in “catch-up contributions”.

There are two limits for 401(k) plans: the tax-advantaged contribution limit (at $19,500/year in 2021, not including employer match), and the total contribution limit (at $58,000) (IRS website). You don’t get any tax benefits from contributing to your total contribution limit, but it’s primarily used for “401(k) megabackdoor” - to funnel money into a tax-advantaged Roth IRA. The limits are shared across Traditional and Roth 401(k).

From what I understand, Roth 401(k) also requires the employer match to be contributed to a Traditional 401(k) account.

Traditional 401(k) is tax-deferred, meaning you don’t pay taxes on the amount contributed, but you pay taxes on withdrawal – this includes paying taxes on the principal (the investment income). In contrast, Roth 401(k) is tax-exempt. You pay your taxes in advance, and investment income or withdrawals are not taxed.

Early withdrawal penalty of 10% applies if you attempt the funds before age 59 1/2, but keep on reading to learn how to get around that. You must begin withdrawing from your 401(k) by age 70.

Traditional and Roth IRA

IRA is an individual plan which allows for tax-advantaged investments. Direct contribution limit is at $6,000, however rollovers are not capped. Meaning the above mentioned 401 megabackdoor funds don’t follow the limit. At age 50, you can contribute additional $1,000 a year. The limits are shared across Traditional and Roth IRAs.

There’s technically an income limit on Roth IRA contributions (MAGI of $140,000 single or $208,000 married), but Traditional IRA contributions can be rolled over into Roth IRA (IRS.gov), effectively nullifying the limit. This is referred to as “IRA backdoor”.

Just like with 401(k), Traditional IRA is tax-deferred: you get a tax refund for contributing to it, but you’ll have to pay back those taxes on withdrawal. Roth IRA front loads the taxes, making earnings and withdrawals tax free.

Traditional IRA can be accessed at age 59 1/2. Roth IRA can be accessed either immediately upon reaching age 59 1/2, or after holding IRA account for 5 years. There’s a 10% withdrawal penalty otherwise, and you must begin withdrawing Traditional IRA contributions by age 72 (Roth IRA doesn’t have the mandatory withdrawal period).

HSA

Health Savings Account is another tax-advantaged investment, but it’s not tied to the employer (however employers might choose to offer an HSA plan). HSA contribution limit is at $3,600 for 2021, which includes employer match if employer offers any. This can be increased by $1,000 if you’re over the age of 55.

HSA is effectively tax-free, meaning that you don’t pay when you contribute, nor do you pay when you withdraw (but there are caveats). HSA can be withdrawn to pay for qualified medical expenses without a penalty. Reimbursing for expenses does not have an expiration date, as long as the expense was incurred after your HSA was established. You can also withdraw HSA without qualified reasons once you hit the age 65 (which is higher than 59 1/2 used for 401(k) and IRA).

Early withdrawals

Now that the basics are out of the way, let’s discuss early withdrawals from each of these accounts.

Traditional and Roth IRA

Let’s look into IRAs first, since the most common way to access 401(k) funds early leverages IRA peculiarities.

5-year rule

I’ve also heard the 5-year rule referred to as a “Roth conversion ladder”.

The most obvious candidate for early access is Roth IRA. Roth IRA contributions (money you put in), can be accessed at any time without a penalty or paying additional taxes. Roth IRA distributions (aka the principle, or the money you’ve earned) can be accessed using what’s referred to as a “5-year rule”.

There are confusingly three 5-year rules when it comes to IRAs, and even more confusingly we care about two of them (the third rule deals with beneficiaries).

The first 5-year rule lets us access Roth IRA distributions within 5 years of owning the Roth IRA account. Simply enough, if you’ve had Roth IRA account for more than 5 years, you can access both the money you put in, and the money you’ve earned.

The second 5-year rule covers rollovers. Rollovers from Traditional IRA or Roth 401(k) need to marinate for 5 years (per transaction) before being accessible. So if you converted between your Traditional IRA and Roth IRA twice – in 2021 and 2022 – you’ll be able to access the money in 2026 and 2027 respectively.

This means that Roth IRA can be accessed if you hold the account for at least 5 years, and Traditional IRA can be converted to Roth IRA (a taxable event) and accessed penalty-free after 5 years.

For example, if you opened a Roth IRA account in 2015, and it’s now 2021 – you can access all the funds at any time without paying taxes.

In a more complex example, you’d convert the Traditional IRA to Roth IRA, and access the resulting money after 5 years:

- Convert a certain amount from Traditional IRA to Roth IRA

- Pay taxes on the transaction

- Wait 5 years (for each transaction)

- Withdraw transaction amount + earnings

This works out similarly for Roth 401(k) to Roth IRA conversion (but with less steps and without taxes):

- Convert any amount from Roth 401(k)

- Wait 5 years

- Withdraw transaction amount + earnings

72(t) SEPP

72(t) SEPP (Substantially Equal Periodic Payments) can be used to sign up for a payment plan from your Traditional IRA (technically you’re able to use SEPP for your Roth IRA as well, but this will incur double taxes). This is quite a commitment, and you’ll be receiving periodic payments from your IRA until you hit the age 59 1/2 (or for 5 years, whichever is longest).

For a Traditional IRA example, you can sign up for SEPP to receive $5,000 annually. This means that each year (until you turn 59 1/2 or 5 years passes – whichever is longest) you will pay taxes on those $5,000, and withdraw the difference.

Additionally, IRA can be used to pay for large medical expenses (within the same year), high education expenses, home-related expenses ($10,000 lifetime limit), and a few more niche cases.

10% penalty

10% penalty sounds large, but it’s really not a terrible choice if the other options don’t work (although I don’t see why they wouldn’t). Given the tax-advantage growth that these assets have been enjoying, 10% penalty is not a steep price to pay. Although understandably loss aversion kicks in, and either a 5-year rule or the 72(t) SEPP sound preferable to paying the penalty.

In case with the Traditional IRA, the penalty would have to be paid in addition to paying taxes on withdrawn amount. Roth IRA only imposes a penalty if you didn’t wait for 5 years since the account creation or the rollover transaction.

Traditional and Roth 401(k)

401(k) can be accessed early (before the required 59 1/2 age) in multiple ways. Both the 5-year rule (aka the Roth conversion ladder) and the 72(t) SEPP can be used to access 401(k) funds.

Roth conversion ladder leverages the ability to rollover Traditional 401(k) to Traditional IRA, and subsequently convert Traditional IRA to Roth IRA (a taxable event). Within the 5 years of that second conversion, you should be able to access the money.

For example, when getting ready for retirement, you may convert all your Traditional 401(k) balance to Traditional IRA. Then each year, you could do the following (this may look familiar from the above):

- Convert $5,000 from Traditional IRA to Roth IRA

- Pay taxes on the transaction ($5,000)

- Wait 5 years (for each transaction)

- Withdraw transaction amount ($5,000)

This works with Roth 401(k) to Roth IRA as well. It’s simpler too, as Roth 401(k) to Roth IRA conversion is non-taxable. Convert Roth 401(k) to Roth IRA, wait 5 years, and withdraw at your own leisure.

HSA

As you may have guessed, HSA balance can also be accessed before the age 65. But it does come with a caveat.

You see, HSA allows you to pay for qualified medical expenses tax-free. No taxes on withdrawal, tax-free growth, and no taxes when paying out. However, these qualified medical expenses don’t expire. As long as you had an HSA account at a time of medical expense occurring, you can get a refund on that medical payment.

This is something that we’re doing – banking medical receipts (which isn’t hard, given the overpriced American healthcare system) to cash in at a later date.

There’s a number of ways to access retirement accounts in the United States. Be it through Roth conversion ladder, 72(t) SEPP, or even by using old medical receipts. And now I have somewhere to look back to once I inevitably forget how any of this works.

-

FIRE in a developing economy

My wife’s cousin recently moved to Cote d’Ivoire, and our latest conversation centered around financial independence and early retirement. The topic is also known under the trendy term “FIRE”. You may have heard about it as “those darn milenials retiring in their 30s”.

A lot of the advice I’m familiar with is US-centric (or covering Canada, Australia, EU countries, and so on). I couldn’t find adequate resources for pursuing financial independence in emergent economies. I tried to research this subject, and here’s what I came up with.

This one’s mostly for you, Myriam – as a follow-up to our conversation.

A pre-disclaimer

I refer to “developing” economies in this article. I’m using this term interchangeably with low and middle-income countries, countries with emerging markets, or pre-industrialized countries. None of those classifiers are strictly defined either. This can be a controversial term, but I hope the reader will bear with me and focus on the primary goal of this article - financial independence outside of countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, UK, and others.

“The” disclaimer

Before I dig in, I want to shine light on my credentials for this article: I don’t have any. I immigrated to the US at age 18. Before that I lived in Russia (which is often considered a developing economy). However I’ve never gotten a chance to become financially savvy in the country. Never held a full-time job outside of the USA.

My wife an I diversify into developing markets (and it’s less than 20% of our portfolio). We don’t have any inherent knowledge or in-depth understanding of emerging markets.

And I sure as hell don’t know what it’s like to live in a pre-industrialized country.

I’m bringing a perspective of a person who’s familiar with financial independence and early retirement in the United States (and vaguely Canada). This piece is a compilation of about 10 hours of research (give or take), with my own context applied to it.

This is not a professional financial advice, and I’ll be making culturally or economically ignorant statements about many countries. Read while having a tub filled with salt nearby.

Working to death

There’s a strong reason why the United States is a birthplace of FIRE movement as a media phenomenon. Limited worker protections, no government mandated vacation days or holidays, no maternity leave, low social security pension – you name it.

In fact, according to 2018 ITUC worker rights index, the United States is placed in “Systematic violations of rights” category. But this is where the first caveat comes in. A major chunk of emerging economies hold a “No guarantee of rights” or a “No guarantee of rights due to breakdown of the law” rating. Make of that what you will.

There’s the cultural aspect to an overwhelming desire to escape workforce: it’s common to live for the weekend in the States. Culturally life is often put on pause Monday through Friday. Enjoying life two days out of seven can be draining.

In the EU, one might take two months off (okay, not quite: 28 legally mandated days off + 7 weekends in between = 42 days). In the States (Canada, Australia, etc) you work to death, and getting out of the rat race is a priority.

This is where I need another disclaimer: I quite like living in the United States. I just think it’s worker protections are shit and should be improved.

Of course the United States and the likes don’t have a patent on working long hours or having workers protection. But there’s a reason why FIRE is prevalent in the industrialized world (in contrast to developing nations). One word: “stability”.

Stability

Despite the popularity of FIRE in the United States, similar formula applies for achieving financial independence in the rest of the industrialized nations. And there’s a constant across those countries: stability.

It’s as simple as that. To ensure your financial future you need to plot and plan ahead. You can’t plan effectively in an unstable landscape. Currency hyperinflation or hyperdeflation, risk of regime and major law changes, corruption and nepotism.

When considering financial independence within developing nations, it’s important to acknowledge and asses the stability of the economy, currency, and political regime. These constants are treated as somewhat of a given in many FIRE conversations, but most recommendations and arguments quickly fall apart when faced with a lack of stability.

There’s no recipe for dealing with a lack of stability, but hedging against it would likely have to be a key part of one’s financial independence strategy. I found a few things that are worth considering – and I’m sure there are many more aspects that escaped my surface-level investigation.

The FIRE recipe

In it’s core FIRE comes down to three principles: increase income, decrease expenses, and invest the difference.

Decreasing expenses is simple, but not easy. Increasing income is hard work that pays off if successful: drastic income increase helps speed FIRE along. Investing the difference carries significant risks due to aforementioned lack of stability.

I’m going to dive into all three principles, but regardless of plans for retirement, building up an emergency fund is always the first priority in nearly every financial conversation. Let’s talk about that first.

Parking cash

The first question you might get asked when talking about FIRE is “do you have an emergency fund?”. There’s always a straightforward recommendation of having N months worth of living expenses in a savings account. Of course this blanket advice breaks down the moment we discuss developing economies.

Lack of faith in the currency or the government puts savings accounts under question. Granted, banks in the developing nations are quick to offer high interest accounts. You might get a 20% return on investment, only to realize that the currency lost 25% of its value in a year.

If the country allows for holding foreign currency, foreign currency could be used to hedge against that. The United States dollar is the most widely held reserve currency. Euro is pegged by 19 countries, making it a relatively stable bet as well. Japanese Yen (JPY) is the third most commonly used reserve currency.

Real estate

I titled this section “Parking cash” and not “Emergency fund” because I wanted to mention an alternative to savings accounts often used in developing economies. Real estate.

While not a place for storing emergency funds, longer term reserves are often held in what’s perceived as the most stable asset – real estate. Due to a significantly lower cost of labor it’s common (and is often sensible) to purchase land, and then build on that land.

Although lower risk than other asset classes, it’s worth examining potential for asset seizure. 1980’s land redistribution in Zimbabwe is the prime example of this. Less stable political systems are at a higher risk for similar events.

Non-primary residence (that is: a house you don’t live in) can be used as an investment – either through having tenants, or through an act of reselling. Investment through real estate is work, and it’s the type of work I don’t think I would enjoy. I haven’t researched anything on the subject and will zoom past real estate and onto another topic.

Earn more

Increased income is an important pillar of reaching financial independence. This is where you say:

I work in a highly specialized (and therefore well paid) field. I can talk all I want about saving and investment, but without the high earner salary, stock grants, and financial benefits my job provides - it would take me decades to get where it takes me years.

It’s possible to ensure your financial future with a lower income. It’s much, much harder.

There’s a significant luck element involved, and I’m not interested in peddling the “work hard and you’ll be rich” narrative. Load of bullshit if you ask me. There are however concrete steps one can take. These steps could open up the right opportunities.

Increasing earning potential is a massive boon in the FIRE world. Directing energy towards this goal might be a higher priority step compared to everything else I wrote about.

The most straightforward way to increase earning potential is through education (either formal or informal). College, university, books, online courses. If formal education is problematic, some industries (e.g. software engineering) are more open to self-taught professionals than others. Yours truly is a good example of that.

Networking is another avenue to pursue. It might be more difficult in certain nations due to inherent nepotism and lack of opportunities.

In fact, many developing countries make vertical mobility problematic due to corruption. In an increasingly connected world, earning internationally could be a feasible way forward to increasing income. That is if you have skills that are worth paying for.

Spend less

Another “duh” topic, reducing your spending in proportion to income is crucial in achieving any type of financial freedom.

Expense reduction is very much a country-specific topic. In fact, it’s highly specific to individuals. Analyzing expenses and putting together a budget is a strong first step. Thankfully, reducing expenses is something commonly covered in media, with plenty of literature available around the globe. That, and this is something financial professionals frequently focus on.

A blanket advice I heard for expatriates living in another country is to avoid expat-friendly stores. Those often come with a premium, and shopping locally might reduce expenses significantly. That’s an extent of my knowledge on the subject.

Invest

“Earn more, spend less, invest the difference”. Generally “invest the difference” portion of the advice implies investing in mutual funds – a mix of stocks and bonds for a set of companies. But as you’ve come to expect in this piece, this advice comes with caveats when living in a developing nation.

General advice for investment into mutual funds is holding a 60/40 split of US/international assets. This represents the weight of the US-based stock and bond market in respect to the rest of the world.

But some countries might not allow for international investments. Some countries might introduce additional taxes on foreign investments. Or investments into certain markets could be made difficult due to local regulations. US in particular makes it more difficult for non-Americans to invest, introducing a number of hoops to jump through for identity verification.

To dig deeper, let’s investigate Cote d’Ivoire as an example - a country Myriam is living in.

Quick history recap of Cote d’Ivoire, a former French colony in West Africa. After gaining independence in 1960, the country enjoyed relative stability until 1999. A military coup led to an economic downturn, and two civil wars followed in 2002 and 2011. 2020 presidential election has resulted in unrest.

From those dates alone, political stability in the region at the moment seems problematic.

On the flip side of the coin, Cote d’Ivoire has the benefit of being a member of ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States. This increases economic stability of the country, by pegging it’s economy (and currency) against it’s neighbors.

This is a nice bonus to economical stability of the region.

We’ve established that blanket investment advice might not exactly work with developing economies. A few questions come to mind:

- What are the restrictions on holding foreign currency or investments?

- How stable is the currency?

- What is the tax situation like?

Let’s dig into each one.

Foreign assets

For financial independence, we’ll want to reduce risks where possible. This means hedging against a single country’s economy.Supporting local economy by investing in a regional stock market is responsible (please do!), but diversification is the name of the game. For a complete portfolio you’ll likely want to hold international stocks and bonds.

Certain countries either might not allow, or make it extremely difficult to hold foreign investments.

In Cote d’Ivoire, there doesn’t seem to be any restrictions on holding foreign assets. That’s a plus. Quick online search didn’t bring up a history of restrictions on ownership of foreign assets either.

Finding a broker that operates in the country of choice (or allows for investment from said country) would be a next step here.

Local currency

Cote d’Ivoire uses West African CFA franc – a French treasury backed currency with a fixed CFA/Euro exchange rate. Political controversy aside, Euro pegged currency offers stability that many developing countries might lack.

To look at currency stability, we can look at an inflation rate or an exchange rate against other currencies. For instance here’s how many CFA a single USD would buy (from 2003 to 2021):

In contrast to that, some quick research surfaces official discussions for introducing “Eco” – a non-French backed currency for the West African region. While this could result in higher economical growth potential for the region, it comes with more risk.

Taxation

Tax laws change how you invest. Our FIRE strategy is carefully crafted to leverage every tax-advantaged account possible: a good third of our assets is held in tax-advantaged accounts. And of course tax laws vary by country.

This is definitely the place where you want to bring in a professional. A quick search (and that’s the keyword: “quick”) indicates that Cote d’Ivoire has 1.5% salary tax, and 1.5% - 10% “national contribution”. Cote d’Ivoire taxes capital gains, dividends and securities. There’s pension both your employer and you pay into, which is nice.

There are likely country-specific tax law peculiarities one can take advantage of to optimize asset growth. This would require much more in-depth research.

Conclusion

Financial independence becomes a completely different beast in developing nations. Whatever little financial knowledge I have is challenged if not outright rendered useless when applied to emerging markets.

Yet there are a lot of directions for future research, and this piece only presents a view through a very much United-States-tinted lens. It could be that FIRE in developing countries might leverage creating a business and using more active forms of income generation.

Many of my findings are superficial, and I touched on a lot of different topics without going in-depth into any one of them. I can dedicate more time to this topic if there’s interest - let me know in the comments.

-

Savings rate plotted over 8 years

I just found my financial records going back to 2013!

I know that doesn’t sound exciting, but for someone who loves putting together spreadsheets this is a treasure trove of information! Well, maybe not a trove, but a sizable chunk of data. I only have two numbers for each month – income and expenses. But that’s just enough to calculate my savings rate!

(income - expenses) / income = savings rateWith this number I can trace a broad outline through the past 8 years of my financial life! I present my savings rate charted over the past 8 years:

It’s smoothed out using a 6 period rolling window, as it’s near impossible to see trends when plotting raw numbers.

This chart tells a life story: starting with a near 0% savings rate in early 2014, a dip in 2017, and a steady 75% from 2018 onward. Let’s trace my major life events!

By the end of 2013 I lived in downtown Philly and was working as a freelance software developer. Per-project pay was decent, but the gaps between contracts reduced the overall income. That, and being a sole breadwinner for a family of two – the funds were running dry and we were living paycheck-to-paycheck.

My then-SO and I had different financial upbringing. My ex-wife and I were both young when we got married, and we’ve never sat down and talked about finance – so I could only guess as to what her relationship with money was. I came from a household of a frugal single mother – we were never short on cash, but the expenses were low. In a rural community food was grown in a large garden, milk bartered from a neighbor, sweaters knitted.

I distinctly remember my partner not having more than a couple of hundred dollars in a bank account when we moved in together. On the other hand, by the time we got married I amassed a nest egg - nearly $20,000. Granted, it’s small in the grand scheme of things – but these were the savings I put together from working low wage jobs – before I learned software development.

You can see us deplete that fund by the end of 2013 and into early 2014. And paycheck-to-paycheck we lived.

In January 2014 I was offered a position with a software company in the Silicon Valley. Things were looking up for our financial life! My then-wife and I moved to a Bay Area suburb.

It took some adjusting after living in downtown Philly. Both our income and expenses increased. Thankfully with the new job we found it harder to keep up with the increasing income: that’s where we settled for the 25% savings rate. A balance between frugality and spending habits.

A marital disaster struck at the end of 2015: my now ex-wife and I split up. What was a downturn in life turned out to be a financial upturn for me. My ex moved back with her parents, and I stayed in the apartment we were renting.

In a bout of coincidental timing, the apartment complex I lived in was scheduled for demolition. I had to move out and look for a new place. Instead, I decided to move into my car. I wrote about that in detail before, if you’d like to read about that.

This is when I became interested in the FIRE movement. If you’re not familiar, “FIRE” stands for “Financial Independence, Retire Early” (I like to think everyone is aware that this is a terrible acronym). The idea is to increase income, drastically decrease expenses, and invest the difference into index funds to live off of indefinitely.

Now that I had an idea where my money can work best, I had an easier time justifying increasing my savings rate. FIRE also turned increasing savings rate into somewhat of a game.

Finally, I negotiated a chunky raise at work. I was underpaid by the Silicon Valley standards, and “I like working here, but I need to be paid X or I quit” tactics worked. Having a reputation for being a high performer no doubt helped.

It’s not surprising that as a culmination of those events, this is where you can see my savings rate beginning it’s climb to a respectable 75%. Occasional spousal support would bump up the expenses, but not having rent to pay and a higher salary made it easy to absorb those expenses.

By the end of 2016 I got my dream job at Google, and moved into a new studio apartment. No, the big dip isn’t just a new place, but it’s strongly connected. I decided to make up for a year of living out of a single suitcase. There’s furnishing the new place from scratch, top of the line gaming PC, a VR headset, and so many things I didn’t need! I definitely went on a bender.

It took me a year to slow down. This is also where my then-girlfriend and now-forever-housemate became more open with me financially: I happened to meet another FIRE enthusiast out in the wild, completely by chance. She reignited my desire to live frugally. End of 2017 was marked by me donating and selling an ungodly amount of things I accumulated over this year, and returning to comfortable living within (or below, depending on how you look at it) my needs.

We moved in together by the end of 2018 and married in 2020. We still keep separate accounts for ease of accounting, and this chart only displays my data for the sake of my partner’s privacy (it’s less work to chart too). Overlaying my SO’s data after combining our finances doesn’t meaningfully change the numbers you see above.

It’s not realistic for us to push the savings rate higher without sacrificing the luxuries we enjoy - like travel or occasional high end dining. So here we are, at a comfortable 75% to 80% savings rate.

My wife and I earn 7 times more than I did when I was a sole breadwinner. Our joint expenses are 60% higher than what my ex wife and I spent 8 years ago. Both my wife and I are in a priviliged position to be high earners in a high paying industry. We’ve gotten extremely lucky where many wouldn’t have.

There’s no real purpose to this post other than sharing my journey. Hope you found something of interest!

-

How much does writing a book earn?

I write about Vim – a modal text editor – a lot. In fact, in early 2018 I was approached by Packt Publishing – what I’ve later learned to be a “quantity over quality” publishing house. Over the next 6 to 9 months I wrote a 300-page “Mastering Vim”.

It was a stressful endeavour, with a publisher rushing to meet internal deadlines and eventually sending an unfinished draft to print. There were many highlights too, like actually cranking out 300 pages of material, or getting to work with Bram Moolenaar – the creator of Vim himself. Now that a few years have passed and the book is at its 3rd edition, complete, and re-released – I’m a lot more happy with the result.

I can write a whole other essay about my experience working with the publisher, but that’s a horror story for another time.

I didn’t write to make money, but it’s nice seeing a couple of hundred dollars trickling in every quarter. Putting together spreadhseets is my favorite past time, so here’s a breakdown of my earnings from the time I wrote a book with Packt.

As of April 2021, the English version of my book has 14 reviews on Amazon averaging at 5 stars (that’s more than I would hope for), which likely helps keep the sales at a somewhat of a steady level.

I was signed into a default “16% of net receipts” contract, with a $2,000 advance given out to me. The advance was split into 5 milestone-based installments: the first preliminary draft, 6 preliminary drafts, the remaining preliminary drafts, the final drafts, and the publication. Although I didn’t urgently need the money, and the publisher may have just sent it as a bulk $2,000 payment after the publication.

Eventually I received a PDF for the first quarter of my book being sold… And here are the financials for Q4 2018:

Print # Print $ E-books # E-books $ 10 $55.50 274 $307.70 A whopping 363 dollars and 20 cents in royalties! I didn’t really think anyone would be interested to read the book, so seeing 284 copies sold I was pretty ecstatic!

Selling printed books seems to pay $5.55 per copy, while e-books only bring me $1.12.

Now I didn’t see any of that money, since I would have to “pay back” the advance. I know it’s called “the advance”, and I knew that I won’t be getting that first check in the mail – but it sucked a bit nonetheless.

After that I received some great news – my book was going to get translated to Japanese! During my last trip to Tokyo I made some friends who were interested in Vim as much as I was, and one of them - Masafumi Okura - decided to translate “Mastering Vim” into his native language. The legend found close to three dozen mistakes in my book too, and is solely responsible for the third edition of Mastering Vim!

Turns out the translation rights are expensive, and I’m getting my cut as well – $1,586.26! That’s more than the first quarter of sales!

Packt advertised my book for a few months or so, but they seemed to have quickly lost interest. I received my first 5 star review on Amazon though, which was great! I spent the next month refreshing Amazon reviews daily, after realizing that to be a path to acquiring a mental illness.

2019 came, and here are my next 4 quarterly statements:

Quarter Print # Print $ E-books # E-books $ 2019 Q1 29 $141.89 202 $337.49 2019 Q2 15 $77.53 71 $194.26 2019 Q3 19 $100.09 57 $207.68 2019 Q4 23 $118.55 117 $255.17 I sold 86 print books and 447 e-books in 2019. You can see the higher numbers correspond to seasonal sales. Notice the prices for Q3 and Q4. E-books sold in Q3 pay me as much as $3.64 per copy, while in Q1 it’s a meager $1.67 per book. Print edition payout stays much more consistent.

Altogether, I earned $1432.66 from my first full year of selling “Mastering Vim”.

Here are my 2020 earnings:

Quarter Print # Print $ E-books # E-books $ 2020 Q1 26 $131.61 112 $414.12 2020 Q2 22 $106.67 77 $379.61 2020 Q3 26 $141.17 74 $325.97 2020 Q4 45 $236.69 166 $458.07 That’s $1,533.38, a $100 more than in 2019. The patterns seem rather predictable, with Q2 and Q3 being slow, and Q1 and Q4 displaying a noticeable spike.

Finally, Packt offers service subscriptions – I believe the subscription is for the courses they offer, but I can’t say for sure. Payout per subscription is small, and I’ve earned $158.10 over the 9 quarters since publishing “Mastering Vim”.

Across $3,329.24 in book sales, $1,586.26 in translation fees, and $158.10 in subscriptions, this adds up to $5,073.60 over the 2+ years the book has been in print. Looks like it can make for a decent supplemental income if you write enough books, but I’m saying that based on a sample size of one.

Throughout this time, my earnings per copy average at $5.16 for a print, and $1.93 for an e-book (using weighted averages for quarterly sales).

And here’s the last number in this post – this one purely for fun. Based on the 16% royalty rate, Packt probably earned $31,710 from “Mastering Vim” so far.